The rollout of Power8 systems that IBM started last year is nearly completed as the company has put its largest Power E880 configurations into the field, giving an upgrade path to customers who had been using Power7 and Power7+ systems to run large databases and online transaction processing workloads and to others who are looking for more scalable machines to run in-memory databases and their applications like SAP’s HANA stack.

The launch of support for SAP’s HANA Business Warehouse on IBM’s Power8 machines, just ahead of the start of SAP’s Sapphire customer and partner event this week, marks the first time that the HANA in-memory database has been certified to run on a system that is not based on an Intel Xeon E7.

And to be even more precise, up until fairly recently, SAP was very strict about the particular configurations of machines that could support HANA, right down to specific Xeon E7 chips with set core counts, clock speeds, and main memory configurations across all of the HANA appliance suppliers. This made it very hard for server makers to differentiate their offerings, but it also allowed SAP to keep the support matrix for HANA simple enough during the early years of the product’s rollout. Now that HANA is more established, SAP is loosening the hardware configurations a bit, allowing for scale up machines from Hewlett-Packard, SGI, and now IBM to address the growing memory capacity needs of HANA shops that want to use the software to power their transactions as well as their data warehouses.

Interestingly, the largest IBM Power E880 systems that will be available starting on June 5 will not be the ones at the heart of IBM’s Solution Edition bundles for SAP HANA, but they could be part of these appliance setups over time. For now, IBM and SAP are only certifying slightly less capacious systems – in terms of both compute and main memory capacity – to run HANA, and to be very precise, only the HANA Business Warehouse data warehouse is being certified on Power-based systems, not the full-on Business Suite transaction processing applications. It is unclear when IBM Power machines will be certified to run the Business Suite.

SAP HANA debuted in 2011 and the Business Warehouse analytics, running across multiple Xeon E7 nodes, came out in 2012. Business Suite for HANA came out in 2013, and allows for customers to run both data warehouse and ERP, supply chain, and customer relationship management software on top of HANA. Earlier this year, Business Suite was gussied up with a new user interface (called Fiori) and application development tools and is now called SAP S/4 HANA. The idea – and one that we see happening all over the IT market – is to create a complete platform for SAP’s 291,000 customers. A platform that does not have a need for Oracle, Microsoft, or IBM relational databases, to be even more precise.

In most cases, including SAP’s setup to run its own $20 billion business, the data warehouse runs in scale-out mode across multiple Xeon E7 nodes that are clustered to do parallel processing while the transaction processing and back-end applications run on scale-up machines that are clustered for high availability. SAP has not – and probably will not – recommend the running of transaction processing workloads across scale-out clusters, and that is why we are seeing SAP and server makers work together to run HANA on top of larger NUMA shared memory machines. Some customers need more memory headroom, even after data compression, than a standard four-socket or eight-socket Xeon E7 machine based on Intel chipsets can deliver. HP and SGI have created Xeon E7 machines with 16 and 32 sockets, respectively, that are in the process of being certified to run SAP HANA, and now IBM is entering the fold with a non-X86 alternative that can also scale up to as many as 16 sockets. Many SAP shops – including IBM itself – use Power-based systems, and many do not want to shift to X86 machines. The Power platform has some advantages when it comes to memory bandwidth, which could be a key differentiation on in-memory workloads like HANA. Perhaps equally importantly, Power-based systems are being deployed on IBM’s SoftLayer public cloud and Big Blue no doubt wants to sell HANA as a service to enterprise customers against Amazon Web Services, which has been selling HANA on the cloud for some time.

IBM is starting out modestly with its HANA efforts, with two appliance bundles, which IBM calls Solution Editions, now and a third one when the last of the Power8 machines comes to market, perhaps in a few weeks if the rumor mill has it right. (IBM is expected to deliver a four-socket Power8 machines, called the Power E850, probably around its Edge2015 conference in Las Vegas next week.)

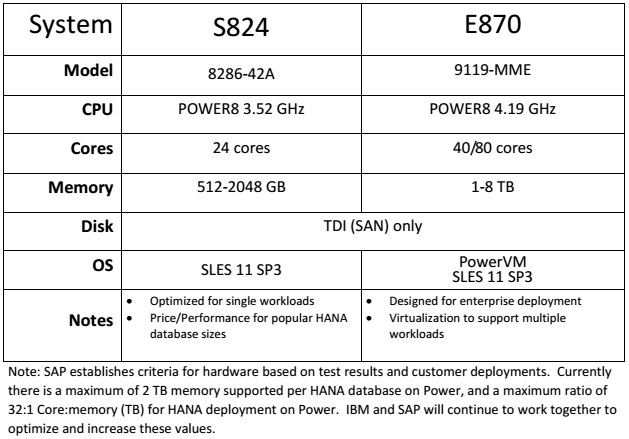

While SAP HANA is technically certified to run across the whole Power8 line – this is news to us, but that is what IBM said — Big Blue has certified SAP HANA for Business Warehouse to run on an entry Power S824 machine with 24 Power8 cores across its two sockets and 1 TB of main memory. This machine, Vicente Miranda, who runs the SAP on Power effort at IBM, tells The Next Platform, is suitable for customers who have databases that are 512 GB in size when compressed. A companion Power E870 machine, equipped with 40 Power8 cores and up to 2 TB of main memory, can handle HANA databases up to 1 TB in size after SAP’s compression squeezes them. Pricing for these Solution Edition bundles was not available at press time. The Power E870 setup runs HANA software inside of a logical partition atop the PowerVM hypervisor, not in bare metal mode. It is reasonable to expect that IBM will get SLES and HANA running in bare metal for customers who want to deploy a bigger image without virtualization.

The Power Of SLES Plus SAP

The IBM Power machines, as noted in the table above, run stock SUSE Linux Enterprise Server 11 SP3, not the SLES 12 release announced last fall and not the new tuned, special version of SUSE Linux’s operating system, called SLES for SAP Applications 12, that the operating system maker has just put out ahead of the Sapphire event. These variants will eventually be certified on IBM’s Power machines running SAP app stacks in general and HANA in particular.

For the longest time, SLES was the only approved operating system for the HANA in-memory database, but last year a special distribution of Red Hat Enterprise Linux for HANA, which included the XFS file system and some compatibility APIs backported from SLES 11 SP3, was made available. Thus far, says Dirk Oppenkowski, global alliance director for SAP at SUSE Linux, the company has not really seen Red Hat in any HANA deals.

SAP application software is sometimes installed on plain vanilla SLES and sometimes on the special editions tuned for SAP, depending on the customer’s expertise. About a fifth of the license revenues from SLES have been driven by the SAP variant, Oppenkowski tells The Next Platform, and there is another chunk that comes from regular SLES sales on X86, Power, and mainframe systems. About two out of three deals for SLES for SAP stacks are driven by reseller partners such as Hewlett-Packard, Dell, IBM, and Lenovo. SUSE Linux has not broken out revenue figures for HANA separately, but the company says that it has over 5,800 customers running on HANA today and that for the past three years sales of SLES for HANA have been rising by 2.5X to 3X on a year-on-year basis. HANA is important to SUSE Linux, obviously, and the company is working hard to maintain its dominant market share of operating systems on SAP applications (with 70 percent of the pie), much as it has a very big piece of the HPC market.

The SAP edition of SLES 12 includes high availability extensions based on the open source Pacemaker project, and SUSE Linux added automatic failover routines to Pacemaker when working in conjunction with SAP systems and application software. This failover is working for two-node clustering for OLTP systems, and Oppenkowski tells The Next Platform that SUSE Linux is working to extend this clustering to the parallel implementations of the HANA platform that underpin Business Warehouse implementations. “This is actually pretty close to rocket science,” he says, which is why this takes a bit longer. Failover for parallel clusters might be done by October; the goal is for the fourth quarter sometime. The SAP edition of SLES also includes setup wizards (aimed mostly at mid-sized customers who don’t write their own scripts or have consultants do it, as large enterprises do). It also has an embedded CLAM antivirus for ensuring that documents and emails coming into the SAP software are clean, plus a feature that allows customers to set page cache limits in the Linux underneath their SAP environments. In normal circumstances, Linux will use all of the cache it can, and for systems that have a lot of SAP users, this leaves the SAP apps little cache of their own and that can adversely affect SAP performance. The tuned up SLES has a higher price tag, at about 1.8X the cost of a normal SLES license.

Topping Off The Power Line

The high-end of the Power Systems line is comprised of the Power E870 and Power E880 machines, which are follow-ons to the multi-chassis Power 770 and Power 780 systems and the biggest machine NUMA IBM has ever created, the Power 795 system from April 2010 that had up to 32 sockets, 256 cores, and 16 TB of main memory all under the same skin and all acting like a single system as far as the operating system was concerned. IBM doesn’t sell very many of the Power 795s and they are expensive to engineer and manufacture, so with the Power8 line Big Blue took some of the reliability features of the Power 795 and moved them over to the multichassis design that it has sold between its midrange and monster systems since the Power5 generation more than a decade ago.

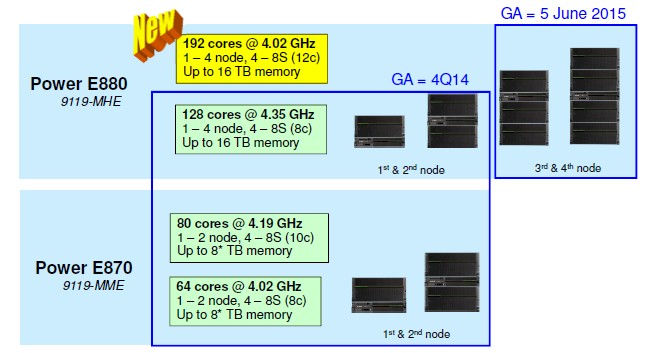

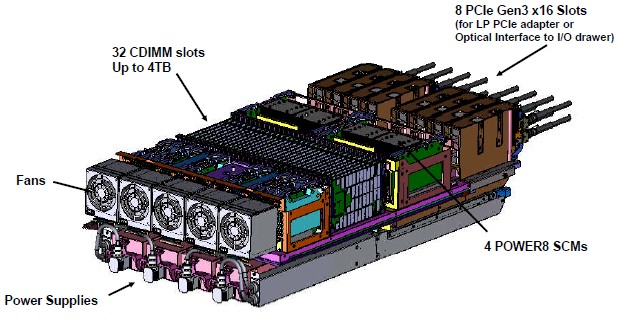

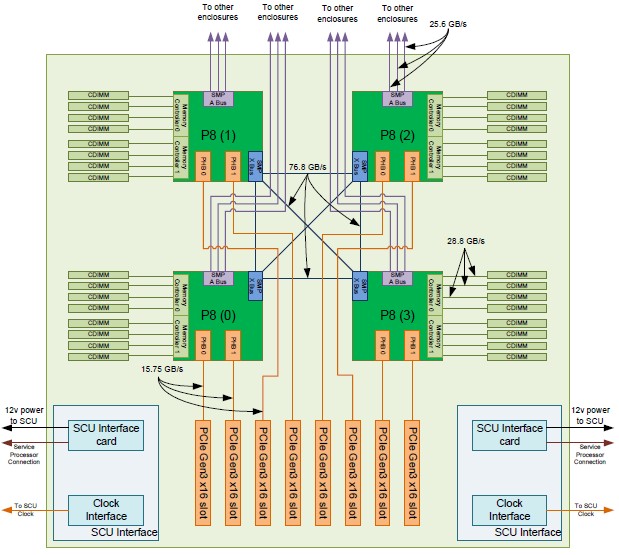

Last fall, IBM rolled out the Power E870 and Power E880 machines, which merges the modular design of the enterprise-class Power Systems machines and adds the service processors, clocks, and oscillators as well as the larger memory footprint of the Power 795 machine. This modular system can have from one to four nodes, which are linked together using high-speed fiber optic light pipes and homegrown NUMA chipsets that have their heritage in IBM’s acquisition of Sequent Systems more than a decade ago. Here is a schematic of what one of the E870 and E880 nodes looks like:

As you can see, this is fairly dense packing for a system. The power supplies are underneath the unit, with fans in the front, followed by dense-packed DDR3 main memory, then the processors, and then the PCI-Express 3.0 peripherals. All of this fits into a 5U rack enclosure. A fully loaded Power E880 has four such nodes, plus a single 1U node that houses the service processors, clocks, and oscillators that makes the machine rugged. The basic building block of the system is a four-node motherboard, which is shown here:

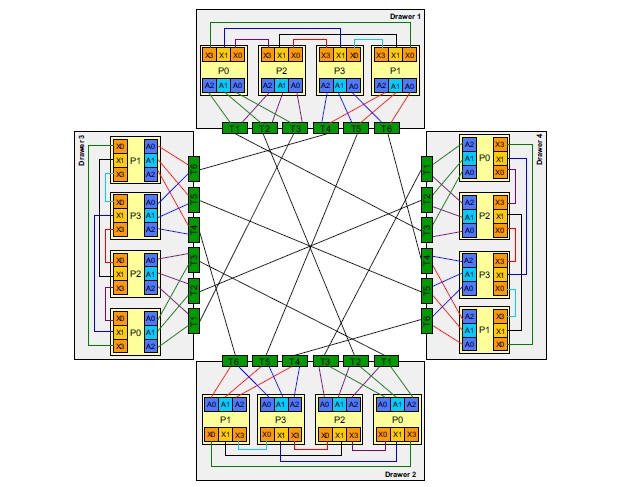

The crossbar interconnect on the system links each of the four nodes on the motherboard to each other using the on-chip SMP interconnect implemented on the Power8 chip. Each Power8 socket has eight memory slots hanging off of it as well as two PCI-Express controllers linking to their own pair of slots and NUMA interconnects that allow two, three, or four of the boards to be linked together into a logical system that has eight, twelve, or sixteen processor sockets. Here is what the NUMA interconnect looks like for the Power E880 fully loaded:

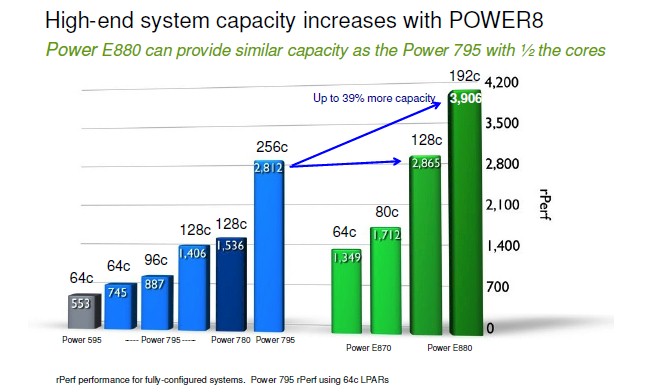

That NUMA interconnect, which is implemented on the chip, scales to sixteen sockets, which is the same as the Power 770 and Power 780 machines and half as many as the Power 795 machine. But, the Power8 chip has a dozen cores in its largest configuration, compared to eight with the Power7 and Power7+ chips, and importantly, the Power8 core can do roughly twice as much work as the Power7+ core. When you wash out the overhead from NUMA clustering in the system, a Power E880 with 128 cores does about the same work as a Power 795 with the same number and a Power E880 with 192 cores can do about 40 percent more work than a Power 795 fully loaded with 256 cores. Here is the performance lineup:

This latter bit is important not just for IBM’s current large system customers running AIX and Linux workloads, but for the future ones who will want to run HANA and perhaps other in-memory databases and their applications on the systems. Running out of compute and memory is the big nightmare for customers moving to in-memory technologies. While 16 TB of memory may sound like a lot, as people keep dumping more data into their warehouses and OLTP systems, the memory could run out quickly. (Incidentally, the performance in the chart above is measured in Relative Performance units, which is a variant of the TPC-C online transaction processing test that IBM uses to gauge the oomph of Linux and AIX workloads on Power Systems machines.)

The fully extended Power E880 will be available on June 5. Pricing information was not yet available, but we are digging around to do a comparison across all the big NUMA machines, so stay tuned.

Once the midrange Power E850 comes out in the next several weeks, that will be pretty much it for the Power8 lineup until IBM gets the “Power Next” chips out in 2016, as we revealed two months ago with a story on IBM’s OpenPower roadmap. This chip, which we have seen referred to variously as the Power8+ or the Power8′ (that is a “prime” symbol), will be followed by the Power9 chip in 2017 that is slated for the Summit and Sierra supercomputers being built by the US Department of Energy through a partnership between IBM, Nvidia, and Mellanox Technologies.

32 CDIMM slots up to 4 TB? 128 GB a slot? Is that DRAM or NAND?

It is a big wonking 128 GB memory card with a Centaur memory buffer/controller on it. And no one else, to my knowledge, in the OpenPower Foundation is using it in their systems. Too big and too expensive.

Nice article, but the main memory is DDR3 dram based CDIMMs and not DDR4