It would be far beyond the purview of The Next Platform to have deep insight to the complexity, scope, and scale of the Chinese economy. All the same, what does – and does not – happen in China over the next several years is going to help determine the key aspects of the platform on which many organizations will run their applications, whether or not they are located in China.

The old adage from the 20th century was that if the United States sneezes, the world catches a cold, or the flu, or sometimes pneumonia. The roots of this saying are even older than the United States, with Klemens von Metternich, foreign minister for the Austrian Empire in the first half of the 19th century, coining the phase when he said when France sneezes, Europe catches a cold.

France was the big deal back then, and the United States was the one modernizing and exhibiting explosive growth.

Now, it is China’s turn. The country has spent three decades architecting and implementing five year plans to become one of the world’s primary factories and has used the wealth it obtained through this transformation to create hundreds of Manhattan-sized cities on its coast, where a third of its population and a relatively new middle class now live. China surpassed Germany as the world’s largest exporter in 2009, and passed Japan in terms of gross domestic product in 2010, taking up the number two position in the global economy behind the United States. And in 2014, China’s stock market blew by Japan’s as well to be second to that in the United States. China does not yet have the largest economy on earth – that could take until 2027 or 2030, depending on who you ask – but it is certainly has the fastest growing one, and in a world obsessed by growth, it might as well be the largest.

The idea for the past three decades has been for the Chinese economy to become more self-sustaining rather than be dependent on exports of products it makes for others and imports of high technology like servers. The cut-throat server market has been transformed by intense competition, and in a desire to get ever-lower costs, server manufacturing has shifted from the United States and Europe to other low-cost centers, with an increasing number of machines made in China even if they are sold elsewhere in the world. Servers are still made in factories in the United States, the Netherlands, Mexico, Singapore, Taiwan, and Japan, but it is increasingly difficult for vendors to sell gear made outside of China into that country. So the IT suppliers that want to be able to capture a bigger piece of the market find themselves having to bend and twist themselves in interesting ways to keep a foothold in China.

“The idea is to build with China, not to make and sell to China. The company will design its products over time, leveraging as much of Qualcomm’s technologies as it needs to. Our initial goal is a server chip, and as you know, it takes a lot of investment and effort to do this right. The competition is tough and we want to make sure we hit the right performance, the right power, and the right price in the marketplace, and once we see traction, we will see where we go from there.”

At the same time, the top server OEMs are facing stiff competition from upstarts like Lenovo, Inspur, Sugon, and Huawei Technologies who are branching out to sell their gear into Africa, Latin America, and Eastern Europe where the incumbent system suppliers, usually based in the United States but sometimes Japan, have less sway. (Lenovo’s $2.3 billion acquisition of IBM’s System x server division in late 2014 was an effort by Lenovo to buy a vast installed base in the US and Europe, much as it did in PCs a decade earlier, and to establish itself as a Sino-American company in the eyes of customers.) And of course, the rise of the hyperscalers and public cloud builders, who often cut the OEMs out of the loop and go straight to ODMs like Quanta Computer or Foxconn for the manufacturing of custom machinery, also puts pressure on the top-tier OEMs. And so does a company like Supermicro, which has a channel that functions like an OEM/ODM hybrid.

Given its sheer size, China will influence the hardware foundation of the next platform in two ways. First, by the technologies it learns to manufacture and, second, by those it chooses to adopt. The two will be intertwined, of course.

The amount of money that server makers are chasing is staggering, and it is no coincidence that both the members of the OpenPower Foundation that is opening up IBM’s Power8 platform for licensing and use by third parties and the collective of ARM server chip makers are both looking to China to give them a much needed volume boost to give them a credible chance against Intel’s Xeon processors in the corporate datacenters of the world. (More on that and other efforts in a moment.)

Matt Eastwood, senior vice president of the enterprise infrastructure and datacenter group at IDC, gave The Next Platform some insight into the Chinese server market and how it compares to the rest of the world.

Coming out of the Great Recession, back in 2009, the server market had cooled down to 7.1 million units and drove only $47.2 billion in sales worldwide, and China accounted for 770,000 units and about $3.7 billion in revenues. So China was 7.8 percent of revenues and 10.8 percent of shipments. Back then, X86 machinery was only about 50 percent of units, with mainframe, RISC, Itanium, and other platforms accounting for the other half. In six short years, the Chinse market has shifted to X86 being 99 percent of units and driving 91 percent of revenues, according to Eastwood. Last year, according to IDC estimates, the world consumed 9.69 million machines and generated $59.3 billion in revenues, and China consumed 2.1 million machines (21.7 percent of the global pie) and $8.5 billion in revenues (14.3 percent) Looking ahead to 2019, IDC is forecasting China will buy 2.8 million machines out of a global market that consumes 11.4 million machines and that this will drive $11.7 billion in revenues out of a worldwide pie of $67.6 billion in sales. If you do the math on those forecasts, between 2014 and 2019, the server market will have a compound annual growth rate for revenues of 4.3 percent, but China will grow at 9.8 percent.

There are two other trends to consider when thinking about China and servers. Back in 2009, the big incumbent vendors inside China such as Lenovo, Inspur, Sugon, and Huawei had 11 percent of the sales inside of China, but as of 2015, their share within the country has grown to 55 percent, crowding out Dell, HPE, and IBM (which just gave up). They are also getting traction outside of China, too, according to IDC. In 2009, these Chinese server makers had a miniscule 1.5 percent of the global revenue share, but as of 2015, they have as a group grown to 13 percent of worldwide sales.

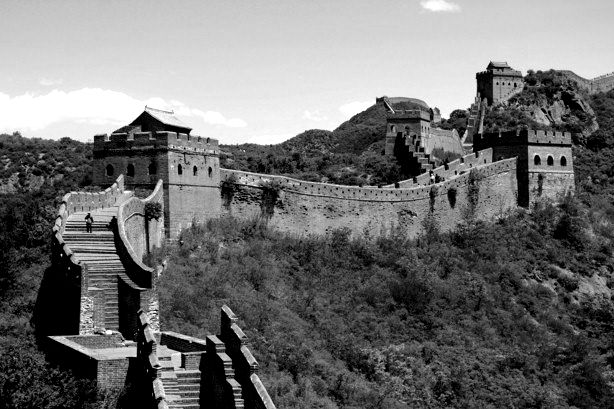

The Great Wall Of Xeons

Having studied the rise of the United States, Japan, and Taiwan as industrial giants, China wants to create a richer economy for itself (in terms of depth, breadth, and GDP), and all of its market reforms over the past two decades have aimed at this goal. Provided its economy does not collapse under the burden of the debts it has used to prop up its real estate and manufacturing sectors, China will have the funds to keep investing in itself and learning how to get better at making things like chips.

Thus far, China has cooked up versions of server-class processors based on MIPS, Sparc, and Alpha architectures for a variety of consumer and HPC uses, and it is even creating its own DSP-based accelerator now that Intel’s Xeon Phi accelerators are not permitted to be sold to certain supercomputing centers in China. None of these have taken off as volume products. But the efforts to develop indigenous ARM and Power chips certainly could.

“If you look at alternative processing technologies and their potential to take off, China is going to be 100 percent behind that in terms of trying to grow ecosystems of technology beyond Intel,” says Eastwood. “They have used security as a rallying cry, but I actually think it extends beyond that, too. They are trying to build this ecosystem of technology vendors that can not only thrive domestically, but globally. They want to become technology exporters and they want to control the IP stack and basically the amount of margin you can extract from selling technology.”

As we have said before, if you look at the profit pools in the systems market, the only ones really making a lot of money in systems are Intel with its server chips, chipsets, and motherboards, and Microsoft, Red Hat, and VMware with their software. Microsoft gets to double dip with profits from its Azure public cloud, provided there are any. China is not going to knock off these big, US-based software suppliers, but it can make competitive Power or ARM processors and use them internally and export them.

While Applied Micro with its X-Gene and Cavium with its ThunderX have both seen some action in China, and a relatively unknown startup called Phytium has joined the ARM server fray with its 64-core “Mars” chip, what China seems to want is an indigenous chip more like its “Godson” MIPS effort, but one that actually succeeds in being adopted in devices rangers from smartphones to supercomputers. ARM is a contender here, clearly, and China is the easiest market to convince to adopt a homegrown solution that has IP that it can license and control. Being able to get custom chips, as Intel sells to US hyperscalers and cloud builders, is not the point. Being able to make its own custom chips as Chinese chip designers and their customers see fit is.

A lot will depend on what the hyperscalers like Alibaba, Tencent, Baidu, and China Mobile do for processors in the next couple of years. Like the US-based hyperscalers Google, Amazon, Microsoft, and Facebook, these Chinese giants can switch out their server processor architectures as they see fit, provided the chips have the right balance of performance, power consumption, and price that Qualcomm is saying that it can deliver with its as-yet unnamed ARMv8-A server chip starting next year. For now, the big Chinese hyperscalers have been content to get semi-custom gear from Dell and Hewlett Packard Enterprise, but that could change as these companies grow fast and want even tighter control of their supply chain than they currently have to rein in costs. Any part of the hyperscaler infrastructure that is selling raw infrastructure cloud services will have to be based on the X86 architecture to support Windows or Linux workloads that would normally run in an on-premises datacenter on X86 iron, but any storage, data analytics, or other service that is exposed as software rather than virtualized infrastructure can be based on any chip. If Microsoft switched Office365 to ARM processors last year, you would be none the wiser. For all we know, it has. Or plans to. Ditto for any chunk of Google’s or Facebook’s app stack.

From Big And Little Blue To Big And Little Red

Doing business in China is a delicate thing because of the sometimes competing interests that China and IT suppliers all have. Everyone is touchy about security and backdoors and such on all sides, and China wants intellectual property and skills. Ultimately, the market is too large not to participate. China is no longer content to let itself be a dumping ground for outside technology, starting with the server and now moving down into the processor inside of that server.

The joint venture that Qualcomm announced with the province of Guizhou in January will see the two companies fund a joint ARM server effort with $280 million, with the province holding a 55 percent stake in the Guizhou Huaxintong Semi-Conductor Technology Co and Qualcomm holding the other 45 percent. Under the deal, Qualcomm is providing capital and intellectual property licenses to help Guizhou design variants of its own ARM server chips from a tech center in Beijing.

Guizhou is the logical place for Qualcomm to form its own partnership because the central Chinese government has designated Guizhou province as a “big data” hub and is building a cluster of green datacenters that will eventually host more than 2.5 million servers and will be used by China Telecom, China Unicom, and China Mobile. It would be as if Qualcomm formed its own private venture with Ashburn, Virginia, where Amazon Web Services, Equinix, and a host of other datacenter operators are located.

No one promised that these servers in Guizhou will all be using ARM chips, mind you, but clearly the idea is that many of them will. Homegrown HiSilicon (owned by Huawei), Phytium, or Qualcomm/Guizhou chips would certainly be the preferred server motors if the chips are widely available and can handle the work. Whatever ARM chips are available and indigenous, they have to actually beat the Intel Xeon because these are businesses, not hobbies, and that is a tall – but not impossible – order. The ARM collective has been able to keep Intel out of smartphones for the most part, after all. It is not like Intel is not trying. It is just that it is as hard to scale a Xeon or Atom down to a phone as it is to scale up an ARM to a server. And the hardest part is finding customers with workloads that fit the chip – and who are willing to go off the X86 standard.

Chinese organizations will be the most eager for this, we presume. And it doesn’t hurt that client and server and possibly network infrastructure will all be based on the same architecture – a benefit Intel itself espouses and largely has delivered between PCs and datacenters. But the PC is not the center of gravity in the world anymore. Our phones and the datacenters that serve them are.

Qualcomm thinks that its partnership with Guizhou will have the advantage over HiSilicon and Phytium as an ARM chip supplier, because it will help drive leading node process technologies at the world’s major fabs, just like Intel does for itself. Americo Lemos, who is interim CEO of Guizhou Huaxintong Semi-Conductor Technology and vice president of the Datacenter Group at Qualcomm that is working on server chips, was a vice president of platforms group at Intel, mostly pushing its mobile processors into devices. He joined Qualcomm last May specifically to get its ARM variants into Chinese servers and datacenters.

“The idea is to build with China, not to make and sell to China,” Lemos explains to The Next Platform. “The company will design its products over time, leveraging as much of Qualcomm’s technologies as it needs to. Our initial goal is a server chip, and as you know, it takes a lot of investment and effort to do this right. The competition is tough and we want to make sure we hit the right performance, the right power, and the right price in the marketplace, and once we see traction, we will see where we go from there.”

That could mean specialized ARM chips for storage, switching, and hybrids that do things like network function virtualization.

As for foundries, the Guizhou partnership will use foundry partners employed by Qualcomm to make its chips, which is no surprise, and similarly, these server chips will have to be at the latest nodes to be competitive, which should mean 10 nanometer processes in 2017. But over time we think there will be a desire to switch to Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation, China’s biggest foundry, and help get it ramped up to the latest processes. In fact, Qualcomm has a separate partnership where it has just assisted SMIC into getting its 28 nanometer processes ramped. But that is two or three nodes away from where server chips from Intel will be in 2016 and 2017.

Qualcomm will continue to work on its own chips and is not just going to use those made in China. In fact, the developing trend is to have a Chinese variant, and other ARM chip suppliers – and perhaps even Intel – may be compelled to do the same in the future.

This has already happened with IBM after it opened up the Power8 processor design for licensing through the OpenPower Foundation. Suzhou PowerCore, a spinoff of an existing PowerPC licensee, started working on its own variant of the Power8 processor from IBM in 2014 and was showing off first silicon of this CP1 processor in a system made by Inspur last March at the OpenPower Summit. Suzhou PowerCore has been vague about its plans, except to say it wants to have a full line of chips aimed at enterprise and datacenter use, and IBM expects for the company to get is first full OpenPower design out the door maybe in 2017. We should hear more about Suzhou PowerCore at this year’s OpenPower Summit in April.

All of this circles back to our thoughts on the Chinese economy. We believe that ARM and OpenPower have the best chances to succeed in the server in China first, and even moreso if the Chinese economy gets weaker. If ARM and Power chips can be brought to market in the 2017 timeframe in volumes and server makers can build systems and the software stack is more mature, what happens if a recession hits in maybe 2017 or 2018? (And there are lots of economists who are thinking a recession can happen around then.) What could happen, if these X86 alternatives offer advantages, is a massive shift to these other architectures as the Chinese governments try to save money while they build out their provincial clouds.

If China sneezes, what the world might catch is an ARM server, or possibly a Power one, too.