All-flash arrays are still new enough to be somewhat exotic but are – finally – becoming mainstream. As we have been saying for years, there will come a point where enterprises, which have much more complex and unpredictable workloads than hyperscalers and do not need the exabytes of capacity of cloud builders, just throw in the towel with disk drives and move to all flash and be done with it.

To be sure, disk drives will persist for many years to come, but perhaps not for as long as many as disk drive makers and flash naysayers had expected – and perhaps only at the big hyperscalers and cloud builders who operate on the scale of exabytes. Typical large enterprises have at most tens to hundreds of petabytes of data, and they are nowhere near needing the exabytes of capacity for the foreseeable future, particularly as they offload some storage to public clouds. For them, speed is always good and if the premium is not particularly high and if the constraints on space and power and cooling are tight in the datacenter, then it is a no-brainer to make the argument to go with all flash arrays.

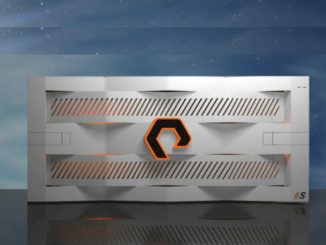

This is precisely what Hewlett Packard Enterprise was predicting nearly two years ago when we started The Next Platform, and what EMC, now part of Dell, was telling us earlier this year as it revamped its storage array catalog with all-flash variants. And it is also what Pure Storage, the upstart market leader in all-flash arrays, is seeing among its customers. It doesn’t hurt that Pure Storage has products aimed directly at the two main kinds of work that enterprises have: The FlashArray/m for virtual servers and databases with block format and the FlashBlade, launched in March with an elegant and sophisticated design, for unstructured data in object and file formats.

“In general, the market continues to cook along,” Matt Kixmoeller, vice president of products at Pure Storage, tells us. “We are continuing on this transaction, graduating from single application deployments to wholesale replacements, and with the FlashArray/m now scaling up to 1.5 PB, we can replace quite large disk arrays with them at this point.”

Three years ago, most flash deployments were driven on an application-by-application basis, maybe accelerating a virtual desktop or database environment. Now, Pure Storage is selling arrays with multiple hundreds of terabytes to petabytes of capacity that are consolidated environments supporting multiple applications and a wholesale replacement of tier one and tier two storage. It is less and less about competing with disk arrays and more about competing against other all-flash arrays, says Kixmoeller.

So how do the storage jobs mix? Do companies just throw everything on the largest all-flash array they can buy? Not exactly, according to what Pure Storage is seeing. Most enterprise environments have a classic private cloud environment that they want to accelerate with flash, where the business applications and databases. When an application gets highly specialized and has unique performance and capacity needs, it gets broken out to a separate set of flash arrays, such as traditional simulation and modeling in the HPC realm or data lakes for analytics or healthcare management systems.

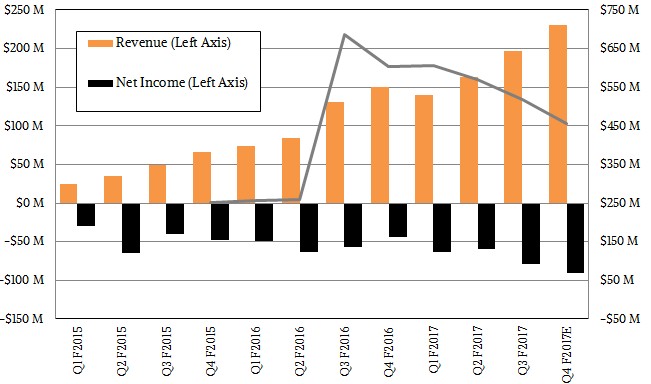

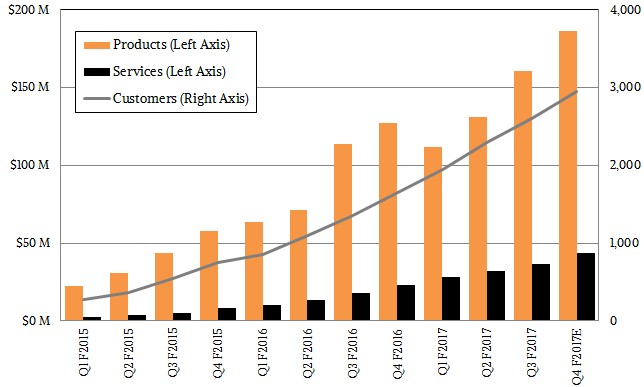

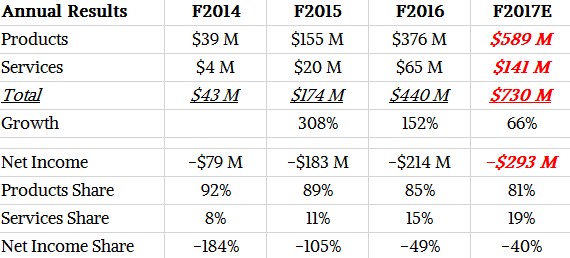

As you can see from the charts and table above, Pure Storage continues to grow its revenue and customer count, and it is now at an annualized run rate that is close to $1 billion a year. But as you can see, profits are still elusive, although it is closing the gap. The issue is that growth is slowing for the FlashArray products, which address a fairly small part of the market with structured data, and the question is if the FlashBlade will give the company another kick and another triple digit growth phase. It is a pretty good guess that when FlashBlade does go commercial next year, it can ride up the object storage wave and all-flash wave together. Reaching the second $1 billion in annualized revenue could take half as long, and that means Pure Storage has a chance to be nicely profitable within the next few years if it can compete against a slew of rivals.

FlashBlade has been in directed availability, with lots of hands on support from Pure Storage, for the past two quarters, and will be in directed availability until the end of the fiscal 2017 year, which comes to a close in January when it will become generally available. The dozens of customers who have put the FlashBlades through the paces are sequencing genomes, making movies, or building self-driving cars.

“These are use cases where conventional storage just could not get them to where they want to go,’ he says. “But in some ways, we were a little bit cautious about if this product was just good for the high end customer, and in this last quarter, we saw more mainstream users come on board, like enterprises doing security log analysis or financial institutions doing risk analysis. We have online gaming firms, software development houses, and web-scale companies. We were quite pleased this quarter in seeing mainstream adoption pick up.”

Pure Storage is not supplying specific numbers, but many dozens have gone through the beta and a larger number have gone through directed availability, which allows customers to deploy FlashBlade into production environments with hand-holding support from Pure Storage. With general availability, Pure Storage will have worked all the kinks out and can open it up for a larger number of sales through its channel.

The future growth for Pure Storage also depends on continued growth for the FlashArray/m line, of course. While the FlashArray/m series does not yet make use of flash cards or drives that support the NVM-Express protocol, which cuts out a lot of the driver junk associated with disk drives and therefore allows for much lower latency links between flash and the peripheral complex on servers, Kixmoeller says that the FlashArray/m line was architected with the NVM-Express protocol in mind and over the next year Pure Storage will be rolling out upgraded models of its storage for structured data that supports NVM-Express.

“This is a pretty big transition for us, and that is because it allows us to go after new stack kinds of applications that have been architected more around the server and direct attached storage model,” says Kixmoeller. “If you look at the new style NoSQL databases or Hadoop or Spark, all of these were born in an era that assume server-local disk and now flash. We have had point deployments for these from time to time, but they have not been a strong use case for FlashArray yet. We see a very aggressive transition with NVMe over the next two years, and that technology is going to find itself in two places: within the storage array itself and then over fabrics as a way to connect the storage to servers in next generation compute environments.”

When the FlashArray/m was first built three years ago, Pure Storage anticipated this transition to NVM-Express for storage, and built it to be upgradable Day One. First, all of the communication to caching devices in the array is based on NVM-Express today and Pure Storage actually created its own dual-port caching devices. Many, many thousands of these devices are deployed in the field today. Pure Storage also laid the piping on the backplane itself to be upgradeable to NVM-Express. With dual-ported NVM-Express flash drives becoming available in volume next year, then the SAS and SATA interfaces that are used to connect flash SSDs to storage controllers are going to go the way of all flesh. Kixmoeller says that the FlashArray/m was architected to absorb NVM-Express flash SSDs when they became available, but adds that as far as Pure Storage’s engineers can tell after tearing down the all-flash arrays from the competition, that competition will not be able to quickly tweak their existing hardware to make use of NVM-Express. Considering that NVM-Express has been around for a long time now in development, this seems particularly short-sighted, but given that a lot of all-flash arrays have their technical heritage in disk arrays, which don’t have enough I/O oomph to need low latency protocols like NVM-Express, this stands to reason. In fact, says Kixmoeller, the transition to NVM-Express flash from SAS or SATA flash is going to be a lot more difficult than the transition from disk drives to SAS or SATA flash.

“In 2016, customers really should not be buying an all flash array that is not ready for this NVM-Express transition because you are going to have a short shelf life for your investment,” Kixmoeller declares. He makes a good point. As for Pure Storage, the company is guaranteeing that FlashArray/m customers will be able to upgrade their storage controllers and flash trays to make use of NVM-Express next year. And Pure Storage is working with its peers in the networking and storage arenas to knock the NVM-Express over Fabrics protocol into shape so it can be used to hook servers to arrays (and we think to better cluster arrays themselves, too) over the next several years.

Our assumption when we analyzed the FlashBlade earlier this year is that Pure Storage would have to drive the cost of the all-flash arrays aimed at unstructured data to be lower than those aimed at structured data, just like Hadoop and NoSQL databases have to be cheaper than relational databases to get traction in the market.

“We kind of expected the same thing, and it has been a surprise in the early adopter phase of the FlashBlade that there was a lot less focus on the dollars per gigabyte than we expected,” says Kixmoeller. “The interesting thing about FlashBlade is that it is being deployed in use cases that are very core to the business, so if you can sequence a genome faster or make a movie faster or make a thousand software engineers more productive or analyze data in real-time, it is very easy for customers to equate that to value. We are finding that the price sensitivity is nowhere as near as we expected, and we are really going up against the expensive, high-end NetApp and Isilon arrays. So what we find is that the price per gigabyte is actually pretty comparable between FlashArray and FlashBlade, and the focus is less about one of them being tier one and the other tier two and more about one designed for transactional applications and the other designed for scale out file and object. Both play at the high end of those two markets.”

We wonder if the biggest cloud builders and hyperscalers who build their own storage software and hardware will be attracted to FlashBlade, and then what happens to the smaller companies that compete with them and the enterprises that emulate them. Will they try to build their own flashy object storage, perhaps with Ceph, or will they go to Pure Storage?

“It is hard to sell to the big three, which is Google, Microsoft, and Amazon,” Kixmoeller concedes. “But we believe clouds number four through a thousand are very much open to us. Cloud vendors pushing IaaS and SaaS account for 25 percent of our revenue and it is a key area for us, and we did see some pickup among service providers with FlashBlade in the last quarter. When you talk about the architecture of the largest clouds, one of the observations that we have is that there was an era when everybody thought that the big guys were doing software defined, that the Google File System model was all software defined storage plus whiteboxes. And one of the hyperconverged vendors talks about moving the Google model to the enterprise. What has been interesting to watch in the past decade is that all of the hyperscalers have pivoted to really investing in software plus quite custom hardware, and they are finding that as you get to the next level of compute and scale, there are just huge advantages of co-engineering hardware and software to build best-of-breed server and storage tiers. They are not going down the path of hyperconvergence and putting everything on one box.”

One last thought: Pure Storage could go one last step and do Pure Compute, adding compute proper to FlashArray and FlashBlade. Kixmoeller was not about to reveal any plans in this regard, but the company could make a compute blade and slide it into every other slot in the FlashBlade, unify compute and storage over the backplane of the device, and be done with it.

“We will see over time about that,” says Kixmoeller. “Part of the challenge that we have seen is that in these deployments, it is not uncommon for companies to be attaching thousands to tens of thousands of simulation and compute cores to the array. The scale to make FlashBlade go at that scale takes an enormous amount of compute, so do you really get the benefits by making it an appliance? I don’t know. As we start to mainstream the product, maybe? It is something we think about, but it is nothing we have committed to do as yet.”

Be the first to comment