You can’t swing a good-sized cat without hitting an enterprise running Oracle software in some shape or form. If it’s not Oracle’s ubiquitous database, then it’s one of its middleware platforms or its enterprise applications in the Fusion suite or its predecessors in the Oracle, Siebel, PeopleSoft, and JD Edwards suites.

Currently Oracle boasts 430,000 customers running its software – that’s quite an installed base. And it’s all teed up to become quite a battleground. Why?

Six months or so ago, news broke that Oracle was laying off a large number of hardware folks. Something like 2,500 Sparc and Solaris development types, along with their entire performance benchmarking group, were shown the door.

In roughly the same timeframe, Oracle roadmaps were updated to show that the newly introduced Sparc M8 processor (and accompanying M8 system) as the only ‘future’ system entries on its indigenous server roadmap. You can read more about this in TPM’s opus, Is The M8 The Last Hurrah For Oracle Sparc?

Oracle, as is its wont, hasn’t commented on the rumors of Oracle Sparc demise or its implied exit from the Sparc hardware market. Or could the company possibly be contemplating an exit from the entire on-premise hardware market? Looking at Oracle’ homepage, it is difficult to even find its system offerings in the midst of all the cloudy messaging.

We think it’s safe to say that Oracle is done when it comes to producing Sparc processors and selling Sparc hardware systems. Oracle has pledged to support Solaris into the early 2030s, which is a good thing for current customers, but it is not something that will attract new customers to the platform.

Oracle’s departure will leave a vacuum in the Sparc enterprise server market. But what’s the value of the market? How big of a vacuum would Oracle’s exit leave and who might fill it? Let’s see if we can answer those questions.

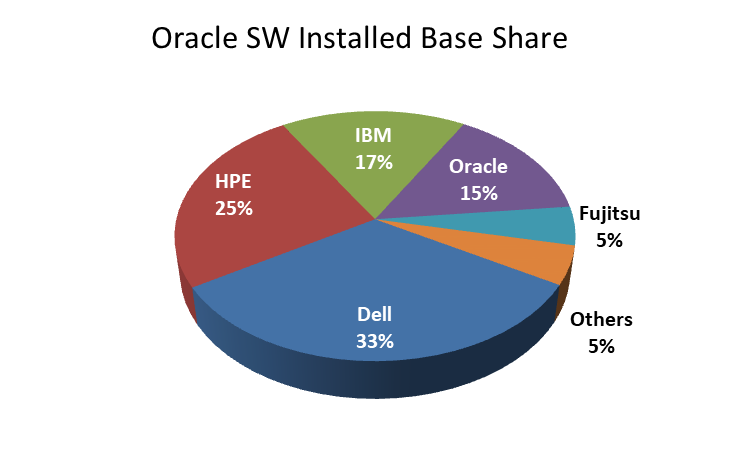

So which server vendors have the largest Oracle software installed base? These numbers aren’t published, so we have done some estimating and cyphering based on what we know about the enterprise server market and through having lived through many server wars.

In first place, with a whopping 33 percent of the Oracle base, is Dell. Oracle and Dell have a very close relationship that dates back to the late 1990s. This is when Oracle realized that there was a very large opportunity in the clustered database space.

Back then, servers were rapidly commoditizing and scale-out was beginning to become all the rage. Oracle, with its Real Application Clusters (RAC) product, took advantage of this by offering a database that could offer good performance and scalability when hosted on clusters composed of relatively small servers.

By partnering with Dell, the combined companies could propose win-win-win deals to customers. Dell wins with the hardware sale, Oracle wins big by selling the significantly higher priced RAC database, and the customers win because they can scale without having to purchase much more expensive scale-up NUMA systems. It was a marriage made in heaven and it resulted in Dell becoming the largest Oracle platform.

Hewlett Packard Enterprise is has 27 percent of the Oracle base, mainly due to the years of being the largest, full-service X86 server vendor. During the exponential growth phase of relational databases and enterprise applications, HPE (thanks to the Compaq server business) did a great job of producing solid systems and, more importantly, providing support to its resellers and direct customers.

IBM trails at 17 percent of the Oracle base, having achieved this due to its solid X86 server product line (which is now owned by Lenovo) and by dint of winning the Unix wars against Sun/Oracle and HPE. Back in the day, when Unix scale-up platforms were the only choice for enterprise-class databases and applications, systems from Sun Microsystems and Hewlett-Packard were the main choice and IBM was an also-ran in a distant third place. This all started to change in the early 2000s when IBM delivered its Power4 systems and started architecting high performance into its line and keeping a steady drumbeat of performance increases on its Power chips while also slashing prices to the bone. (Well, for a Unix system, anyway.)

Once IBM had dominating performance (like 2X in some cases) versus Sun and HP, Big Blue laid waste to the Sun/Oracle and HP installed bases, replacing them at a furious rate. It didn’t hurt that IBM is, well, IBM, and had the widest global reach of any hardware supplier at the time.

Ironically, Oracle comes in at number four with 15 percent of the Oracle software installed base. And the company only got that share through the purchase of Sun in 2010. But despite being the incumbent manufacturer of Sparc/Solaris systems, they haven’t been able to grow this base significantly. They’ve seen more growth out of their X86 based Linux systems, but that’s still not much to write home about in revenue terms. Oracles hardware revenues have dropped from $5.37 billion in 2014 to $4.15 billion in 2017 and were eclipsed by cloud revenue for the first time.

The only other major player in the Oracle software base is Fujitsu, with an estimated 5 percent of the market. Fujitsu is an interesting case because it produces its own Sparc processors and systems that are completely compatible with existing Solaris operating systems and software. In fact, the latest Fujitsu Sparc processor tops the SPECrate_int2017 and SPECrate_fp2017 charts when it comes to per-core performance.

What Is At Stake?

This is a bigger market than many think. While there aren’t many numbers to refer to, it is a relatively straight forward task to estimate the number of Oracle systems in use today and the potential revenue at stake in this market.

First, we start with Oracle’s 430,000 named customers. Each of these customers is running at least one server with Oracle software, while some large organizations might have hundreds or even thousands of servers devoted to Oracle machinery. So let’s make a reasonable, and probably conservative, estimate that the average customer has twelve systems. This gives us a system installed base of 5.16 million servers (430,000 x 12). That’s a pretty big number.

The dollar value of the installed base is a simple calculation; you just multiply the units by your estimate of the average Oracle server price today. This isn’t all that easy. Some will argue “a server is a server” and thus propose a low number – maybe $15,000 or so.

But when thinking about an average price for a system that will run Oracle, we have to consider what the server will be doing. These systems are mission critical for most organizations and will be configured for both high performance and maximum availability. This means fast processors with many cores, lots of memory, and plenty of hardware RAS features. When you go out and configure a system like this, the total is probably going to be well north of $20,000 and could even range to $50,000 or more.

For our analysis, we are going to use an average price of $20,000, which is probably conservative. Given this, the total value of today’s Oracle software installed base is just over $103 billion – which is might surprise many of you.

| Vendor | Estimated Customers | Installed Base Share | Units | Installed Base Value |

| Dell | 141,900 | 33 percent | 1,702,800 | $34,056,000,000 |

| HPE | 107,500 | 25 percent | 1,290,000 | $25,800,000,000 |

| IBM | 73,100 | 17 percent | 877,200 | $17,544,000,000 |

| Oracle | 64,500 | 15 percent | 774,000 | $15,480,000,000 |

| Fujitsu | 21,500 | 5 percent | 258,000 | $5,160,000,000 |

| Others | 21,500 | 5 percent | 258,000 | $5,160,000,000 |

| Total | 430,000 | 100 percent | 5,160,000 | $103,200,000,000 |

Even though Oracle’s hardware share of its own software installed base only is 15 percent, that still represents a very healthy $15.5 billion worth of gear. If you agree with us about Oracle dropping Sparc, and maybe leaving the on-premises market completely, then there are 64,500 customers with 774,000 servers who will have to decide what they’re going to do in the future.

Over time, each of the 64,500 Oracle Sparc customers will have to do something with their Oracle workloads. Oracle wants to migrate them all to the Oracle Cloud, of course. But there are other options out there. Customers can shift their workloads onto hardware from another vendor. They could also move their Oracle workloads to another cloud vendor, like AWS.

The 64,000 Customer Question

Can we predict the future? No. But we can take some educated guesses based on analysis and experience. And we are going to swing for the fences in our guesstimates for how this whole situation will shake out.

Oracle Cloud, 50 percent: We think Oracle will likely be able to get only half of their existing customer base into their cloud. Some of you might be shaking their heads at this, saying it’s much too low. Some of the factors shaping my estimate are Oracle’s standing with customers – they tend to see Oracle as evil. Perhaps a necessary evil, but evil nonetheless. We have done plenty of customer sentiment surveys and have never seen a vendor as hated as Oracle. The company has a reputation of taking advantage of its customers in every way possible, all in an effort to exploit every opportunity to rake in more money.

When customers moves to the Oracle Cloud, they are essentially outsourcing their Oracle workloads to Oracle. Given how customers regard the company, are they likely to want to give Oracle even more leverage over them? Or will they try to stay out of the Oracle Cloud by any means necessary and look for alternatives?

Other Cloud, 10 percent: Moving to another cloud, like Amazon Web Services, isn’t necessarily the best course of action when it comes to TCO, performance, and to a lesser extent security. Taking Amazon’s AWS as an example, customers will pay a 1.0 licensing factor for their Oracle instances in AWS. Given that the list price of Oracle’s database is $44,000 per core, the difference between a 1.0 license factor and the 0.5 license factor you can get for on-premises Sparc and X86 hardware looms large. Plus, we have seen test data from VARs and resellers that shows a potential 20 percent to 25 percent Oracle performance penalty for current AWS systems vs. currently available on premise Sparc and x86 servers. This is probably due to configuration differences between the two, plus networking overhead.

Dell/HPE, 20 percent: The largest incumbent Oracle vendors, with 33 percent and 25 percent estimated market share respectively, will probably harvest 20 percent of the remaining Oracle installed base. The sheer number of customers they have between them (nearly 250,000) should ensure that they will learn about a large number of Oracle Cloud deals on the table.

Dell and HPE are likely to compete very hard against Oracle for these workloads, offering the latest and greatest hardware at highly discounted prices. They understand that any workload that goes into the Oracle cloud will likely never come out again – so it’s now or never for Dell and HPE when it comes to nabbing these system sales. This should net them nearly $3 billion each in additional sales over the next three to five years.

IBM, 10 percent: With its new Power9 systems , IBM has a chance to take at least 10 percent of the Oracle installed base. IBM has account presence in the vast majority of Oracle accounts, and Power 9 should have enough of a performance advantage vs. x86 to win their share of installations against Dell/HPE.

However, IBM faces an uphill battle in this quest. They are at a TCO disadvantage, since Oracle has them pegged at a 1.0 license factor. This means that licenses for an IBM Power system are twice as expensive as they are for X86 or Sparc systems. IBM also needs to make a much bigger noise in the market about their virtues versus the competition. A potential $1.5 billion windfall over the next few years should certainly get their attention, right?

Fujitsu, 10 percent: Fujitsu isn’t as well-known as Dell, HPE, IBM, or Oracle. But the Japanese company has been producing Sparc chips and building or selling Solaris/Sparc systems for decades. Its newest system, the M12, scales up to 32 processors and 32 TB of memory. The chip fueling this box is the Sparc64 XII, a twelve-core CPU with 8 threads per core running at 4.25 GHz. We dug into the SPEC_int_rate2017 database to figure out how well it performs. We were surprised to find that per core, it outperforms systems based on Intel’s top of the line Platinum 8180 by anywhere between 18 percent and 29 percent depending on the size of the system.

Fujitsu also has some significant non-performance advantages over other competitors. First, they have a 0.5 Oracle license factor, giving them 50 percent lower software fees than IBM. They are also the only incumbent running the Solaris operating system and can thus easily migrate any Sparc/Solaris workload onto their boxes. If a customer has a highly customized Sparc/Solaris environment, or is a big Solaris fan, then Fujitsu will be their only choice in the future.

Fujitsu sells North American systems through Oracle direct sales and resellers. If Oracle does exit the Sparc business, this leaves these sales channels with only the cloud (low commission payout) or Fujitsu systems (higher commission) to sell. Wonder what choice they will make? Fujitsu has the opportunity to add $1.5 billion to its top line if it can manage to raise their profile and exploit its advantages versus the competition.

When it comes to revealing their plans, Oracle is much like North Korea (but without an active nuclear program). The signs today point to Larry going all in on the Oracle Cloud and leaving hardware to the dustbin of history. This could change, of course, but everything Oracle is currently saying (and not saying) argues for the cloud. Given that 64,000 customers and a potential $15 billion is at stake, it’ll be interesting to see how it all works out.

Oracle DB Enterprise Edition licenses are $47,500 per Oracle Processor.

An Oracle Processor is a core (1.0X multiplier) for IBM POWER, HP Itanium, and AWS and Azure (even though AWS and Azure are Intel).

For generic Intel, an Oracle Processor is two (2) cores (0.5X multiplier).

Oracle DB Standard Edition is much less expensive than EE, and I suspect many of those 430,000 customers are actually on DB SE.

It’s an interesting dependency. Fujitsu is the sole remaining SPARC innovator (Oracle M8+ CPU is just a maintenance release) but yet they are 100% dependent on Solaris advancing so that they can remain competitive with X64 Linux , and need more than just Solaris dot sustaining releases and any ad-hoc features that the few remaining Solaris developers throw in.

Oracle had traditionally been a software company, moved into integration with a support focus, forced into buying a significant partner [Sun Microsystems] before a competitor purchased it.

If Fujitsu SPARC64 had sufficiently caught up in features to SPARC [the fastest processors on the face of the planet] – Oracle may be able to reduce risk & return to being a pure Software Company with an integration focus.

With Oracle continuing significant Solaris developments, the market will have some more exciting features coming soon!