There isn’t really a systems business so much as a collection of them, all unique and all facing their own particular challenges. Among all of the current crop of vendors, IBM has been at this the longest as a free-standing, independent organization, but there are some very ancient systems businesses that still have a few coals glowing at Hewlett Packard Enterprise and one fairly old one whose fire has nearly died out at Oracle. Fujitsu and Hitachi and NEC all carry on with their own proprietary and Unix systems, albeit in much more diminished form.

IBM did its best to ride the X86 server wave, but the lack of profits – at least the way that Big Blue ran its manufacturing – compelled it to sell of its System x business to Lenovo more than five years ago, leaving it with a very profitable legacy System z mainframe business and an aspiration to take on the X86 base with its Power Systems. This was a tough row to hoe for the Power8 and Power9 systems, given the enormous price/performance advantages for raw compute that Intel Xeon and AMD Epyc processors enjoy. But in many cases, where memory and I/O bandwidth, or NUMA scalability, are the most important attributes of a system, then the Power Systems machine can hold its own perfectly well and even trounce X86 or Arm alternatives at the CPU and the system level. And the System z mainframe is still second to none as a batch processing I/O beast for online transactions and batch processing, hammering away at work at 98 percent or higher CPU utilization for years at a time without respite.

The persistence of those System z mainframes underpins the very existence of Big Blue and its ability to capitalize on other waves of computing in the datacenter while at the same time bringing those capabilities back home to the mainframe base for those who are quite literally too addicted to their mainframe applications to ever think of giving them up. They can wrap new software layers around them, they can create adjunct applications that run beside them and in conjunction with them, but unplugging them is not only unthinkable but virtually impossible.

Here at The Next Platform we are not as interested in the venerable System/360 and its follow-ons except to say that this is a touchstone for what a platform can be if done properly with the technology of its time and how that platform can be extended over time. Say what you will, but you could build one hell of a big Linux server, with hundreds of cores and thousands of partitions and tens or hundreds of thousands of containers, complete with Red Hat Enterprise Linux, Ansible, Kubernetes, and OpenStack – and many of the remaining 6,000 or so mainframe shops in the world do just that while at the same time running their core business applications atop the proprietary z/OS operating system. And the fact that they can do both of these things gives IBM the revenue stream and profit pool to continue to invest not only in System z processors and systems, but also to continue to invest in Power processors and systems. But we make no mistake about it, the System z line pays a lot of the bills for IBM’s Systems group, and without taking down exascale-class supercomputer deals in the United States or Europe, it is much harder for Big Blue to plow a lot of money in Power chip and system development. Thus far there is no indication that IBM will cease building Power chips and selling Power systems, but a lot of the people who pushed IBM’s hybrid computing strategy, lashing Power chips to GPUs and FPGAs, and Linux on Power as well as the OpenPower Foundation collective have left Big Blue. And the top priority for Arvind Krishna, IBM’s new CEO and the mastermind of the Red Hat acquisition, and Jim Whitehurst, IBM’s new president and formerly the CEO at Red Hat, is to make the Red Hat software stack grow and get IBM its $34 billion back and give it some cred in the modern datacenter.

IBM has specifically said that it will do nothing to give its own systems a leg up when it comes to running Red Hat Enterprise Linux, which protects its largely X86 customer base and growing Arm customer base, and it is really not clear what more IBM can do to make Power Systems a viable alternative to running Linux workloads. IBM’s Power9 cannot win on price or core count or memory bandwidth against AMD Epycs, although it does have some I/O bandwidth and NUMA scalability advantages for sure. If the price was right – meaning lower – then IBM could probably win more deals for its Power E950 four-socket servers and the Power E980 servers, which scale from four to sixteen sockets in a shared memory system. AMD can’t do this with “Rome” Epyc systems, and neither can Ampere Computing with its Altra line or Marvell with its ThunderX2 or future ThunderX3 lines. If the cost of NUMA machines didn’t rise faster than the memory and I/O bandwidth of the increasingly embiggened machines, IBM could compete better for modestly sized clusters. Even a Parallel Sysplex shared memory cluster of System z15 mainframes tops out at 32 systems, each with sixteen sockets (192 cores) and 40 TB of main memory, for a total addressable memory space of 1.25 PB (yes that is petabytes) and 6,144 cores running at 5.2 GHz. The Power E980 system has 192 cores per system across sixteen sockets as well, but there is no Parallel Sysplex for it to extend the shared memory. Which is a bit of a wonder, really. It might make one hell of a Linux cluster and, if you hung lots of GPUs off the Power9 CPUs, then it might make one hell of a hybrid AI-HPC supercomputer.

It’s something to think about.

Reverse the logic. Most distributed computing systems, which are much more loosely coupled than a Parallel Sysplex, have maybe 100 or 200 nodes, tops. Yes, Google uses Borg to distribute work to as many as 50,000 nodes at a time, but this is not a shared memory system by any stretch of the memory bus or imagination. With the average machine having maybe 48 cores using Xeon SPs, that’s somewhere between 480 and 960 cores. A Parallel Sysplex of five Power9 big NUMA E980s would cover 960 cores – and it would still be a shared memory system. In theory, the programming model would be easier than trying to use MPI or some other protocol to dispatch work across the cluster. And IBM could grow that cluster by another factor of 6.4X if necessary to reach 6,144 cores and a whopping 2 PB of main memory.

Just chew on that for a moment. Google can’t do that, and maybe the next search engine that can do that can beat Google. What’s old is always what’s new again.

To our knowledge, no one has used Parallel Sysplex clusters on mainframes to the full scale, and a lot of that has to do with the cost of the systems, the software, and the networking. But as we have pointed out before, using a $50 million system at nearly 100 percent utilization is practically the same, in terms of real price/performance, as running a $10 million system at 20 percent utilization. It is very hard to keep these distributed systems truly busy all the time, and IBM is the master of this in the enterprise. This is IBM’s real edge, and the issue is more that it created a knife with Power Systems when what it needed to forge was a broadsword.

That’s our two cents as we contemplate IBM’s second quarter financial results.

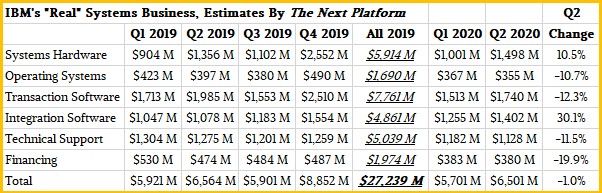

In the quarter ended in June, IBM’s sales were off 5.4 percent to $18.12 billion, and net income fell by 45.5 percent to $1.36 billion. IBM’s Systems group had $1.85 billion in external sales to customers and reseller partners plus another $240 million in internal sales of System z and Power Systems iron to other IBM groups, mostly Global Technology Services for outsourcing agreements but also for the IBM Cloud, which is now hosting Power servers as rented infrastructure. Some of those internal Power Systems sales are also for DS8900 SANs and ESS GPFS clusters, which are sold as appliances. If you do some math with IBM’s numbers, then it had a total of $1.5 billion in systems (meaning servers or storage) hardware sales in Q2, we think up 10.5 percent, with a gross profit of $866 million, up 46.4 percent, by our model. Operating systems revenue across these platforms was $355 million, we reckon, down 10.7 percent, with a gross profit of $291 million, down 13.1 percent. Add it all up, and the combined Systems group had sales of $2.09 billion externally and internally, with a pre-tax income of $248 million. (IBM’s percent change numbers for system and operating system sales are in constant currency, not as reported.)

IBM does not report its system sales by product, but said that Power Systems sales were down 28 percent, while storage was up 3 percent and System z was up 68 percent. A little less than half of that revenue was for “cloud,” whatever that means. With virtualization since 1989 and monthly software licensing since the dawn of time, it is hard to argue that just about all of IBM’s System z sales are not for “on premises cloud.” These definitions are somewhat meaningless, especially in a world where you can have a bare metal cloud. We are interested in counting the money and the profits, call everything else what you will.

As best as we can figure from our own model, IBM’s external Power Systems revenues were down 29.5 percent to $365 million, but storage platform sales based on Power iron rose by 60 percent to $77 million. On top of this, there is another chunk of Power Systems sales to other IBM groups and operating system sales for Power iron. So that core Power Systems business was on the order of $442 million. But when you add in operating system sales and sales to Global Technology services, it is probably on the order of $550 million to $600 million. (The error bars on how much Power iron went into GTS are pretty big, but reasonable guesses.)

The point is, this business is larger than IBM wants to admit – it was about 2X what IBM had in the first quarter of 2020 – for reasons that are not obvious to us.

The thing that we always keep in mind is that, despite it all, Red Hat or not, IBM is still predominantly a systems company.

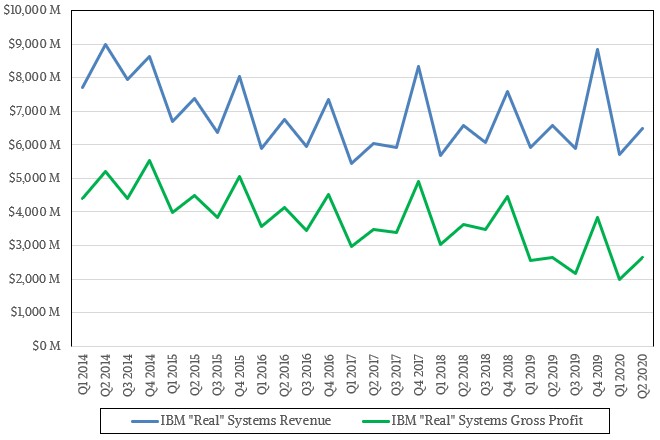

By our estimates, IBM’s “real” systems business based on its System z and Power Systems platforms – including servers, storage, whatever switching IBM itself sells, operating systems, transaction processing software, various system-level middleware but not databases, technical support, and financing – accounted for $6.5 billion in sales in Q2 2020 – down 1 percent.

Gross profits for this business were $2.65 billion, up a smidgen, and about 41 percent of revenues for these base systems. Operating profits will be less than this – IBM doesn’t say how much, so we can’t do a direct compare to Intel’s Data Center Group in this regard – but for the past two years, they have been roughly on the same revenue stream.

IBM can still grow this business, but it has to start thinking inside and outside of the box. What we have suggested above is just one possibility.

Since Global Foundries cancelled their 10 and 7nm processes, the Power10 is years behind schedule. For this reason, it’s not surprising that sales of IBM Power is currently in decline. Given that Samsung had a license to manufacture the DEC Alpha but didn’t further suggests little historical interest or ability in high-performance computing. It also doesn’t help that current Power systems rely on very old Linux kernels.

The Fujitsu A64FX and Fugaku supercomputer demonstrate that it’s possible to create a high-performance computing architecture that is better than a heterogeneous GPU-based system both in raw performance and the ease in which scientists can apply that performance to real problems.

On the other hand, the Power9 on its own had noticeably mediocre float-point performance even at release. Trying to remedy that with tightly coupled GPU accelerators created a hardware platform too expensive for entry-level usage with an inflexible proprietary software stack–good riddance of that idea.

The only way to sell big systems is if a successful customer can start small and grow. The only way to sell small systems is if they are easy to program and can be scaled to big systems. While the huge systems work well, both Power and Z are missing performant entry-level systems that entice customers who need to start small and grow. In my opinion, Power10 needs to be powerful enough on its own to create an attractive entry-level system.

The hype of composable compute infrastructure sounds great, especially in that interview with William Starke on this site last year. The reality, however, could be much different: an impossible to program, afford or control Frankenstein style of machine. Conversely, the way in which scalable vector extensions, tofu and high-bandwidth memory were added to the ARM architecture machine by Fujitsu resulted in architecture in which the features needed for high-performance computing blended together well.

Thanks for the thought provoking article!

Thanks for the article, just a couple of comments…

Mainframes staying busy at 98% is because they have batch workloads with no guarantees of completion time. It’s effectively using the “idle loop” of the OS to handle programs that might complete today / tomorrow / whenever. It also does a great job of limiting the physical pages of memory that these background jobs can use.

About 25 years ago I was working for a very large travel provider and they were so proud that their largest TPF system could run at 100% all day and still provide great response times. My team did some detailed analysis of the logs and we found that about 0.1% of transactions actually failed, but they were using 28% of the CPU. Actual useful workload was 72%

There’s nothing in a mainframe that can beat the physics of queuing theory, they just use these numbers for marketing.

Also, as I understand it, Parallel Sysplex is not shared memory, the coupling facility is used to coordinate locking and exchange of data pages.

A.