Today, the Gerstner era of International Business Machines is over, and the Krishna era is truly beginning, as Big Blue is spinning out the system outsourcing and hosting business that gave it an annuity-like revenue stream – and something of an even keel – in some rough IT infrastructure waters for two over decades.

The spinout, which IBM chief executive officer Arvind Krishna, who took over the helm of the company in April, will create an as-yet-unnamed and publicly traded company that is tentatively being called NewCo, focused on strategic outsourcing and system hosting for some 4,600 companies in 115 countries around the world. And while IBM has not said this, NewCo will also be something else: IBM’s largest customer, which has some interesting ramifications for both companies.

Perhaps nothing could illustrate the changing nature of IT infrastructure in the enterprise better than this deal does, and it also shows that Krishna is very serious about repositioning IBM for growth and is dedicated to its Red Hat enterprise software and IBM Cloud businesses as the means to provide growth while at the same time staying in the systems business proper and retaining the annuity revenue streams that come from its System z mainframes and Power Systems iron. Frankly, we have been more than a little worried that Big Blue might be contemplating spinning off its systems hardware businesses, and we are pretty sure that this has been contemplated over the years, given all of the things that IBM has sold off: the manufacturing of low-end and high-end printers, disk drives, networking equipment, PCs, X86 servers, and chips being the notable ones in recent decades.

We talk about companies embiggening a lot here at The Next Platform – think of what Intel has done with acquisitions in recent months and what Nvidia has been doing in the past year – and sometimes we have to talk about them ensmallening. This is inherently less fun, but no less important. Every company has a narrative arc, just as every person does.

That has been the case with both Hewlett Packard, which split into HP Inc and Hewlett Packard Enterprise and sold off its software and IT services businesses, but the free-standing and much smaller HPE has also bought the SGI and Cray supercomputing businesses to push higher up the IT food chain. The original Hewlett Packard tried to build a copy of the IBM behemoth of the 1990s, and Dell followed suit, with both trying to build up and buy services businesses. HP bought Electronic Data Systems and Dell bought Perot Systems, which interestingly were both founded by one of IBM’s top mainframe salesmen from the punch card era, none other than Ross Perot.

The hosting and system outsourcing business was is big chunk of the Global Services behemoth that Big Blue spent decades building up starting in the late 1980s as Perot was being very successful at EDS. None other than Sam Palmisano, who would rise the be IBM’s president and chief executive officer, lead this effort. But he was given that job to create Global Services by Louis Gerstner – the first and still the only outsider to ever run the company – when Gerstner was tapped from American Express in 1993 to run an IBM that was having what its own executives called “a near-death experience.”

When Gerstner took over running IBM, what he found was a mess, with warring systems and software factions and a company that often competed with its partners. More than a few people were suggesting that IBM should break itself up into Baby Blues – one for mainframes, one for PCs, one for proprietary and RISC/Unix minicomputers, one for software, one for services – to try to unlock some of their inherent value. Gerstner was having none of that, and we have always guessed that Gerstner must have figured the situation was so dire – IBM’s finances from the time certainly prove that it was – that the best thing he could do was keep IBM together and reposition it as a services company that would sell and support anything customers needed that also happened to sell its own systems.

And for the most part, this strategy worked. IBM bought the IT consulting business from PriceWaterhouseCoopers – a deal spearheaded by Ginni Rometty in 2002 and putting her on track to succeed Palmisano as the CEO at IBM. The acquisition of SoftLayer in 2013 helped get IBM into the true cloud infrastructure business, but a little late in the game. That may not matter as much in an enterprise world that is going to go hybrid cloud – which in this context means a mix of on-premises and public cloud infrastructure to be sure, and maybe multiple public clouds for some. And that is why the IBM Cloud, the public cloud utility that has been expanded from SoftLayer, is staying with IBM and not going to NewCo. Krishna was the architect of the Red Hat acquisition last year, and it will be his legacy, not Rometty’s, and the spinning out of NewCo puts the deal on it. Perhaps they should have called it OldCo, given the legacy nature of this part of IBM.

None of this means that NewCo is a bad business. Riding down a legacy business is also a way to make lots of money, and plenty of companies do it and do it brilliantly. Those mainframes and big iron Unix boxes are the heart of mission critical systems of record, and more than a few hyperscalers and cloud builders have such systems doing their back office functions, too. (SAP ERP systems are popular, which makes sense considering when these companies exploded into being in the late 1990s or early 2000s.) These systems are not easy to replace because they have trillions of lines of code encapsulating the very operations of the business, and in many cases, changing it would result in no benefit and incurring lots of risk.

IBM’s services business is wide and deep, so some explanation is in order before we get into the details of the spin-off and what it might mean for the part of IBM that remains.

Global Services is absolutely huge, even if IBM doesn’t talk about it as a single entity anymore – it stopped doing that a few years back because it made Big Blue look as lopsided as it really is after selling off so many hardware businesses. In the trailing twelve months through June 2020, the latest financials we have from IBM, Global Services had $42.82 billion in sales, 56.7 percent of its total $75.50 billion in sales. Within this, Global Business Services had $16.39 billion in sales, comprised of consulting, process, and application management services. Global Technology Services, which sells infrastructure and technical support services, had $26.43 billion in sales. These businesses are all flat to down, and they are a drag on IBM’s top line and they are less and less profitable, too. And that is always the reason that IBM spins something off or sells it off. That said, these businesses all combined had a backlog of inked deals worth $107.1 billion and did signings of new deals worth $8.2 billion as the second quarter came to an end in June.

There is no way that IBM would ever spin off all of Global Services, of course. Some of the units are still quite profitable, generating billions of dollars per quarter in gross profits. This is nothing like mainframe hardware or mainframe systems software does, mind you. But there is good money to be had here for someone who wants to run NewCo and for someone who wants to run the pieces that Big Blue is keeping. It is all a question of striking a balance and managing reasonable expectations.

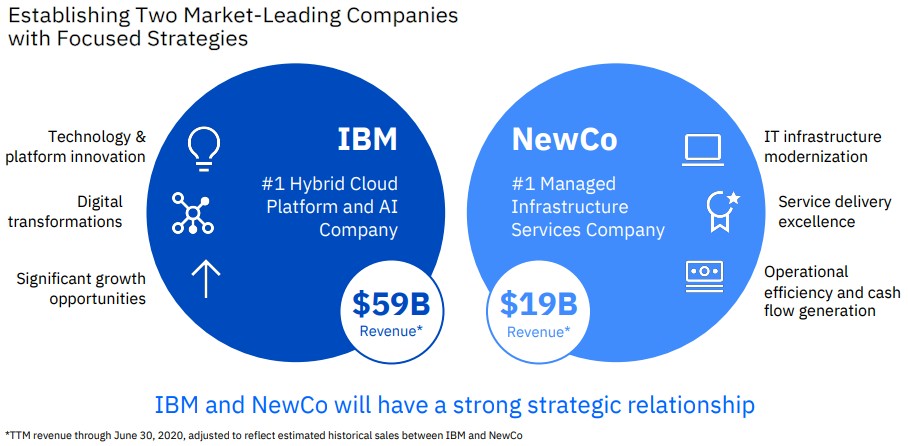

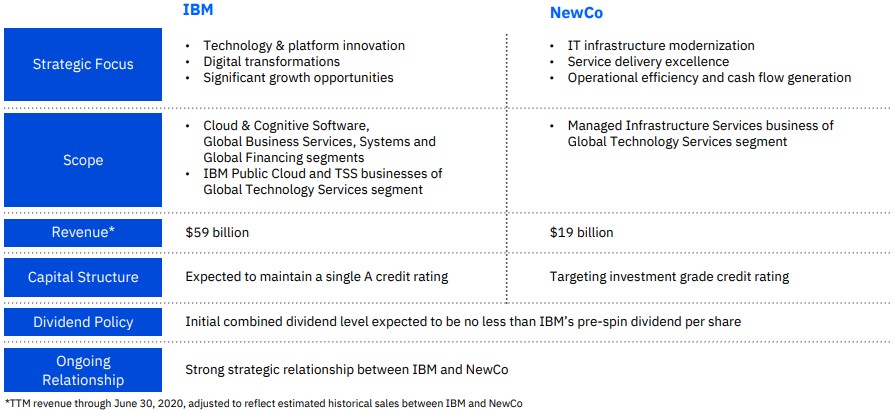

We are sure that there are many who would brook at Krishna’s assertion during a call with Wall Street analysts going over the NewCo spin off that the remaining IBM is the “#1 hybrid cloud platform and AI company” but no one would argue that it sells $59 billion worth of systems and software and infrastructure services. A significant portion of that revenue stream comes from System z mainframes and their monthly licenses for operating systems, databases, middleware, and other tools, and a reasonable chunk comes from sales of the Power Systems stack. There is a certain amount of dough that IBM gets financing and supporting this and other gear, too, although IBM has been backing away from financing and tech support on non-IBM iron.

With around $19 billion in estimated sales in the trailing twelve months, NewCo is indisputably going to be the largest managed infrastructure services company in the world, as Krishna suggested – unless you count Amazon Web Services, which is twice as big at $39.98 billion in the trailing twelve months, and ignore Microsoft Azure, which should be roughly the same size as NewCo for the trailing twelve months. (It is hard to precisely tease that out of the market research and Microsoft financial reports.) IBM contends that NewCo is twice the size of the nearest managed infrastructure services competitor, and did not elaborate on what this means or who that might be.

NewCo will be providing hosting and network services, infrastructure modernization (meaning upgrading iron not rewriting or refactoring or refacing applications), hybrid multi-cloud management, and services management and has a $60 billion backlog with around 45 percent of that being “cloud.” Perhaps NewCo will explain what this means when it is an independent public company. NewCo will have 90,000 employees, which is a fairly large portion of IBM’s workforce, the last estimate we have seen numbers 352,600 people worldwide.

The spinoff of NewCo is expected to close by the end of 2021 and is also expected to be tax free based on US federal tax law. IBM estimates it will have around $1.5 billion in cash charges to do the spinoff and another $1 billion in bookkeeping charges to do the deal, which is a significant amount of dough. But that is the price you have to pay sometimes. Particularly if no one was willing to buy NewCo, which might have otherwise generated some immediate cash for Big Blue. (Remember: IBM had to pay GlobalFoundries $1.5 billion to take over its IBM Microelectronics chip division and booked a total of $4.7 billion in charges to do the deal.) IBM expects to take a $2.3 billion charge to cover most of these NewCo spinoff costs at the end of 2020.

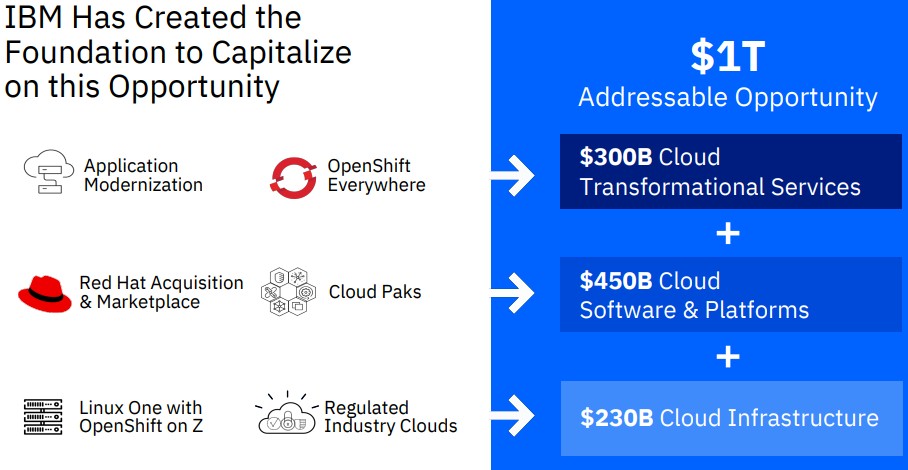

What Krishna wants to focus on its Red Hat and getting more companies on the hybrid cloud journey, and he walked through a bunch of stats to give Wall Street something to chew on. Both Rometty, who remains chairman of IBM for a while yet, and Krishna have been banging the drum for several years that there is a $1 trillion hybrid cloud opportunity in the enterprise (well, it is actually $980 billion, but what is $20 billion between friends), pointing out further that more than 90 percent of enterprises currently have hybrid cloud environments – we told you it would be this way from the beginning, AWS – and moreover that 75 percent of enterprise workloads are not yet in the public cloud and that around 60 percent of the hybrid cloud opportunity, or $600 billion, is in highly regulated industries that are freaked out by security and the paperwork to prove they have it to myriad government agencies. Here is another way that IBM is dicing and slicing that opportunity:

This is obviously a multiyear opportunity, but Krishna did not say what it is. The ratios of the spending are interesting, just the same. The cloud infrastructure, whether it is on premises or on the public cloud, is 23.5 percent, cloud infrastructure software and platforms represent 45.9 percent, and services to transform applications to be cloudy in either VMs or containers represents the remaining 30.6 percent. At this point, Red Hat has grown by 20 percent from $3.5 billion to $4.2 billion in the trailing twelve months, which is at about the pace that both IBM and we expected. Krishna said that the number of large deals that Red Hat has been able to take down has doubled since IBM took over, but the growth rate has not really accelerated, so Red Hat must be losing steam somewhere else since the deal went down. IBM has over 2,400 hybrid cloud customers and over 200 engagements through Global Business Services that are leveraging Red Hat technology. IBM also has more than 300 partners in its hybrid cloud channel.

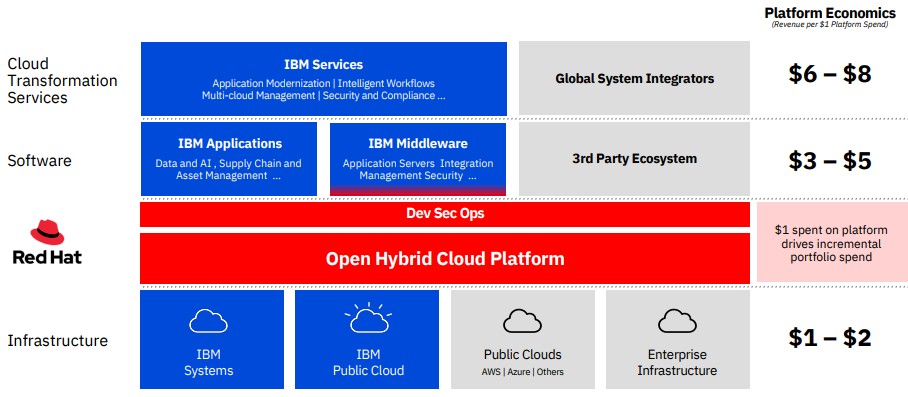

But here was the most interesting chart that Krishna presented during the NewCo spinoff:

For every $1 that companies are spending on Red Hat infrastructure software – Enterprise Linux, Enterprise Virtualization, and OpenShift mostly, we guess – they spend $1 to $2 on the underlying on-premises or public cloud infrastructure to run it, another $3 to $5 on various applications and middleware, and another $6 to $8 on all kinds of services. So don’t get the wrong idea. IBM still intends to have a very large services business in the Hybrid Cloud era. In fact, it is counting on it.

One last thing. The Global Technology Services group at IBM – and specifically the outsourcing and hosting business that are being spun off into NewCo – is very big buyers of IBM systems, including servers and storage. In fact, the word we hear is that the majority of the inter-company spending for IBM Systems group is for hosting and outsourcing customers. That was $814 million in 2018, $727 million in 2019, and $781 million in the trailing twelve months. We don’t know how much IBM controlled the upgrade cycle for its outsourcing and hosting customers, but we suspect that it has helped from time to time when a new line was coming out or a product was at the tail end of its time. With NewCo in charge of its own fate and upgrade cycles, it will be interesting to see how this changes. One big change for sure is that these sales will not be reported as external sales and in the official revenue numbers, which will have the effect of making IBM’s Systems business look bigger unless – unless you were doing this math along with us all along.

It is very surprising that IBM is spinning off the legacy services…!! Perhaps IBM is spinning off legacy services to generate cash to invest in hybrid cloud. Global technology services is a huge part of IBM services. Personally I think IBM needs to concentrate on generating cash flow & profitability.

Is that mean NewCo will have all mainframes?

No. Just the ones it buys from IBM to host stuff or ones Global Services already “owns.”