The server market is a multi-cylinder engine, with eight major hyperscalers and cloud builders all doing their thing almost independently of each other and of the economic conditions at large and the rest of the market being more subject to the waxing and waning of the economic tides.

In that sense, we suppose, quarterly server sales are representative of the overall economy, a kind of leading indicator, but it also shows points out the haves and have nots if you can drill down into the data. If you have access to the data, that is.

Here at The Next Platform, we rely on the public pronouncements that come out of the big market researchers like IDC and Gartner, and we track what they say about the products that go into the datacenters of the world and think about it very carefully to try to gain some insight into what people are doing and why.

This just got a little harder to do that since IDC has decided to not publish its famously detailed quarterly server revenue and server shipment data, which was updated recently to provide insight into what was going on in the fourth quarter of 2020. Most of the big server suppliers and component suppliers have reported their financial results, and IDC uses this data, we presume, to finesse its models. Which is why there is always a ten-week or so lag between when a quarter actually ends and when companies like IDC reveal their latest models.

The data that IDC is revealing is a lot less useful, but the charts that it did provide, statements that IDC made accompanying the charts, and the historical data that it has already published do allow us to reverse engineer the Q4 2020 data to a certain extent and thereby get a reasonable, if less precise, approximation of what was going on in the server racket as last year was coming to a close. (To our mind, it doesn’t look much like 2020 ended at all. It still feels like March 2020 as far as we can tell. . . .)

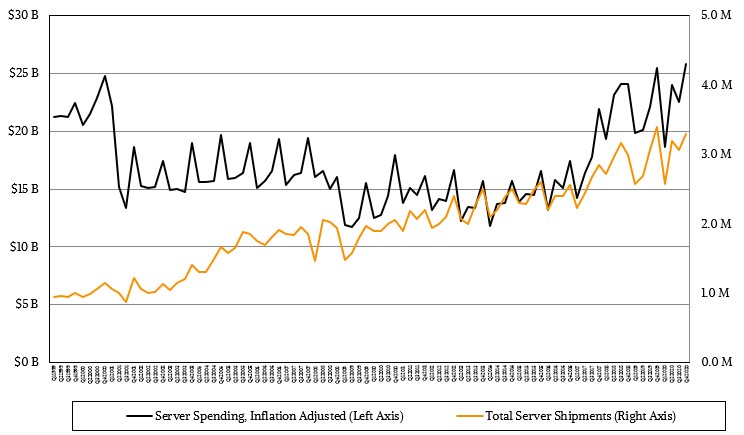

In the quarter ended in December, IDC reckons that server shipments declined by 3 percent to nearly 3.3 million units worldwide, but revenues rose by 1.5 percent in the aggregate to $25.8 billion, we think thanks in large part to companies buying more heavily configured machines. The shipment decline, we think, was in part caused by the launches of the AMD “Milan” Epyc 7003 processors, which were unveiled last week, and the impending Intel “Ice Lake” Xeon SP processors, which are expected sometime in April if the chatter on the wire is right. While both Intel and AMD started shipping these processors in Q4 to the hyperscalers and cloud builders, the shipments were not at full volume and many customers who can wait for them are waiting for them. Given this, the fact that somewhere around 6 million chips were probably sold in Q4 – the market is dominated by dual-socket servers, with a shrinking number of single-socket machines for SMBs and a reasonable number of systems with four or more sockets counterbalancing that a bit – is amazing and attests to the steady demand that the top several hundred server buying organizations in the world represent.

If you inflation adjust the IDC quarterly server revenue data going all the way back to 1999, as we have done for fun, and plot shipments against this, you get a good sense of how healthy the server market really is compared to the dot-com boom.

And the answer is, this is like a sustained dot-com boom, and that is what it feels like as our businesses are even more reliant on IT than they were more than two decades ago. That increasing server count per quarter is a very good indicator of how dependent, but if you make some assumptions about the average performance of a server across these machines, the aggregate performance embodied in all the servers sold in Q4 2020 is on the order of 450X that of all of the servers sold in Q1 1999. So the performance increase needed to run the world is a hell of a lot more than the 3X you might infer by looking at the shipment data above.

IDC did provide a little bit of insight into what was happening with servers in Q4 2020. Volume server shipments (meaning machines that cost less than $25,000) represented $20.4 billion in sales, about 79.1 percent of the total. Midrange iron, which tends to be boxes with GPU accelerators or with four or more CPU sockets and which cost between $25,000 and $250,000 in IDC’s way of carving up the server market, had a sales spike of 8.4 percent to $3.3 billion in the period. High end machines, which include big iron NUMA X86 and RISC/Unix iron as well as IBM System z mainframes, posted a 21.8 percent decline compared to the year ago period, falling to $2.1 billion.

Paul Maguranis, senior research analyst of Infrastructure Platforms and Technologies at IDC, said in the statement that sales of servers in China rose by 22.7 percent, while the rest of the world declined by 4.2 percent. We strongly suspect that the big Chinese online retailers – Alibaba and JD.com are the two biggies – spent a lot of money on infrastructure to support Singles’ Day sales on November 11, which is a big cause of infrastructure buying every year in the third and fourth quarters in the Middle Kingdom. Alibaba and JD.com had $115 billion in sales on November 11, 2020. That’s for one day, and it represented an aggregate of 62.8 percent higher revenue than on November 11, 2019. Alibaba and JD.com are probably good on infrastructure until the next Single Day rolls around, so there is every reason to believe that China will see a return to slower growth in server spending in the coming quarters.

As for other geographies, server revenues in the Latin American region was up 1.5 percent, and the Asia/Pacific region minus China and Japan) was off 0.3 percent. Sales in North America dragged down the average, falling 6.2 percent, with Canada down 23.7 percent and the United States off 5.5 percent. Japan had a 6.3 percent decline, and Europe had a 1 percent drop.

In terms of form factors and processor choices, IDC hasn’t talked much about blade servers in years, but said this time around that blade server revenues declined by 18.1 percent while rack servers saw a 10.3 percent rise. Sales of X86-based machines rose by 2.9 percent to $23.1 billion, and therefore sales of non-X86 servers were down nearly 9 percent to around $2.8 billion. IDC did not put out shipment figures by architecture, but did say that shipments of servers based on AMD X86 processors rose by 100.9 percent (meaning they doubled) and shipments of servers based on any Arm processor rose by 345 percent (meaning they were up by just under 4.5X). Both, IDC reminded everyone, have small but growing installed bases.

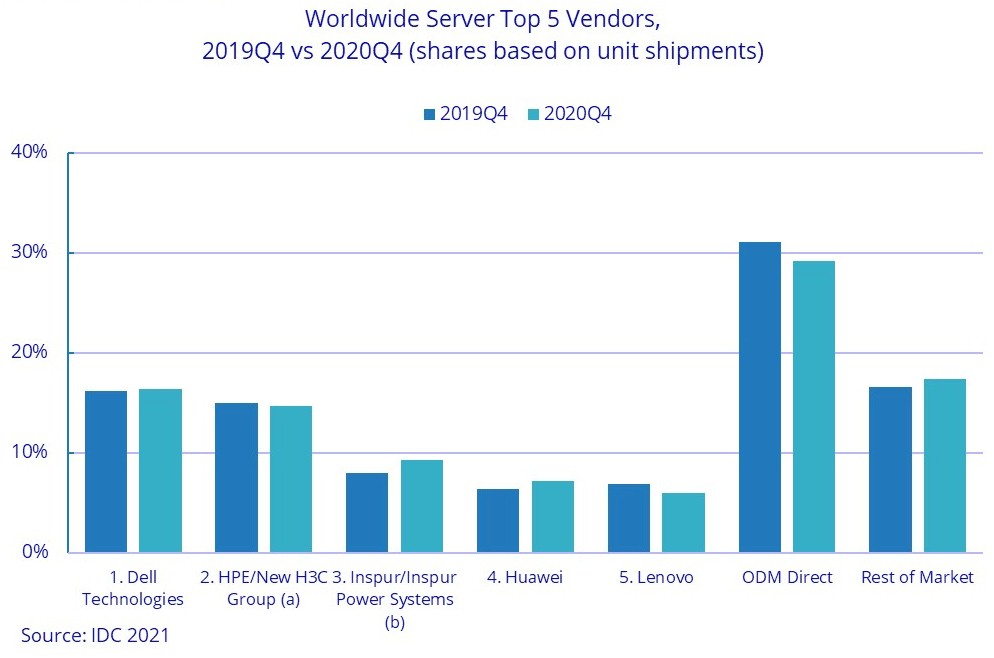

Now, let’s talk about vendors. Here is the chart that IDC published for year-on-year revenue share by vendor, including the original design manufacturers (Foxconn, Quanta, Inventec, WiWynn, Jabil Circuit, Tyan, and some others) as a separate group:

And here is the chart that shows year-on-year shipment share by vendor, with the ODMs as a group:

Hewlett Packard Enterprise owns a 49 percent stake in Chinese server maker H3C, but for some reason its total sales are added to HPE’s numbers. This seems fair because HPE basically had to give up trying to sell into China by itself because of China’s desire to control technology and distribution of that technology within its borders.

For whatever reason, when IBM set up a joint venture with Inspur to have that company resell its Power-based machines in China, the revenues from those Power machines are put entirely into the Inspur bucket. IBM has the same 49 percent share of this joint venture that HPE has in its H3C joint venture. Maybe this is really more of a technology licensing deal, especially given the fact that Inspur is expected to replace Supermicro in making Power Systems machines that IBM resells. (That was the rumor last year, anyway. We shall see when entry and midrange Power10 machines launch next year.)

In any event, this has the effect of pumping up Inspur’s revenues and shipments and artificially reducing IBM’s. Our point is that IBM’s Power Systems business is not as weak as it looks, especially considering that China was a big growth market for that hardware platform for the past decade and probably still is given the number of very large government agencies and companies that need big NUMA iron to support their workloads. Having hundreds of millions of people in a state or a metropolis area means needing big iron by definition. Some of Inspur’s growth in the charts above, and some of IBM’s decline, is due to this effect. But certainly not all of it. IBM is at the tail end of the Power9 cycle and its System z15 mainframe cycle, which is on the upswing, can’t fill in the gap completely.

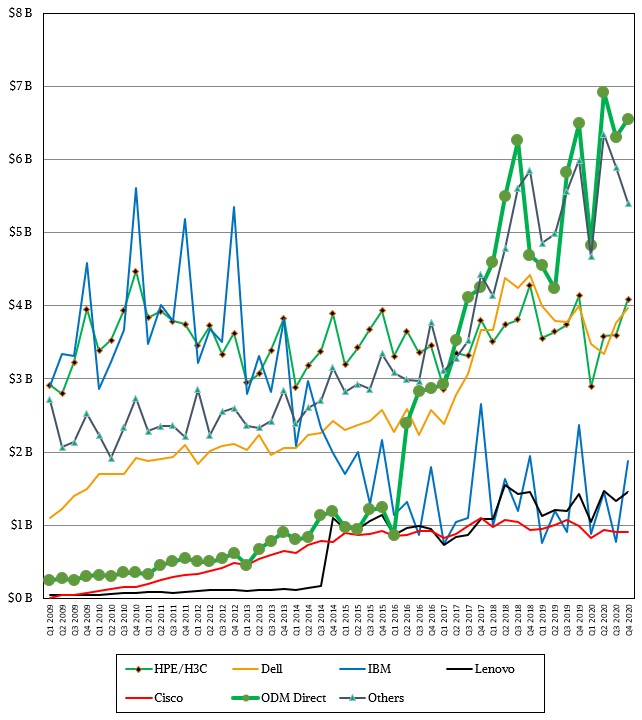

Just for fun, we took the revenue chart above and counted the pixels in each column and worked the ratios backwards to reconstruct revenues by vendor in Q4 2019 and Q4 2020. This data is only as good as the resolution of the graphics. Here is the historical chart based on IDC data compiled over time, with the estimated data we created for Q4 2020 tacked on:

Based on those estimates, we think HPE posted sales of around $4.09 billion, up 1.2 percent, in Q4 2020 the way that IDC reckons revenue (server configuration plus base operating system) and Dell came in with a decline of under 1 percent to just under $4 billion. This manner of estimating would put IBM’s revenues at $1.88 billion, down 20.7 percent, and Lenovo up 1.4 percent to $1.45 billion. The ODMs would have posted sales of $6.55 billion, a record but only up just under 1 percent. We are estimating based on our own gut and the skinny financials of Cisco Systems that it had $910 million in server sales, down 8.1 percent, and that leaves all the other vendors raking in $5.4 billion, down 9.8 percent. If you take Huawei Technologies, which we reckon had $1.54 billion in sales, up 17.6 percent, and Inspur, which we reckon had $2.17 billion in sales, up 25 percent, then the remaining other server vendors absolutely imploded as a group, down 42.6 percent to $1.7 billion.

These are, as we point out, just our estimates based on that IDC chart above and historical data from IDC. This is the best we can do, under the circumstances.

Be the first to comment