Creating a platform is a massive technical challenge. We have seen many technically elegant ones in recent years – Cloud Foundry, Engine Yard, the original OpenShift, Photon Platform, Mesos, OpenStack come immediately to mind – that didn’t quite make it, and importantly did not rise to the economic challenge of making enough money to sustain the continued development and support of that platform to have to reach tens of thousands, to hundreds of thousands, to millions of customers.

We have been watching the Hashi Stack, an absolutely unique and scalable platform that can run Kubernetes if you really want to but which has its own way of doing containerized infrastructure, as it comes together. Mitchell Hashimoto and Armon Dadgar, the co-founders of HashiCorp, have spent more than a decade putting together the Hashi Stack, which we took a hard look at last June when we had a fun conversation with Dadgar about the company’s aspirations to be the next platform. In December, HashiCorp went public, and having done that, we can begin to track its financial progress alongside of its technical progress.

It is particularly difficult to build a sizeable platform business when all that you sell is software, and it is doubly difficult on the economic front to build a successful – meaning both pervasively used and generating revenues and profits – platform business based on packaging up open source software and selling support subscriptions to it. Red Hat, which is now part of IBM, is the by far outlier, having built up its Enterprise Linux business as part of the Dot Com Boom and then increasingly adding both breadth and depth to its software stack to create most of a complete platform. We think Red Hat needs more virtual networking and while it controls Ceph object storage, it does not have a strong offering in file systems – Gluster has been largely mothballed for nearly a decade – or block storage.

But, after some bumpiness in the early years, when the Dot Com Boom went bust and Red Hat had to figure out the right balance of pricing for its support subscriptions and professional services, it managed to create a business that generated around $5.34 billion in 2021 and would have, if free-standing, had around 15 percent of that drop to the bottom line, contributing about $800 million or so of the $4.7 billion in net income for 2021, based on past Red Hat trends up through 2019 before IBM acquired it for $34 billion. Red Hat is 1/11th of IBM’s revenue, but 1/6th of its net income. And just about all of its IT budget story outside of the legacy System z and Power Systems platforms.

That’s a pretty good model to shoot for, but at the early stages that HashiCorp is in, the numbers just are not pretty and that is because building fast takes more cash than it generates for a couple of years, which is why companies get equity investors and why they go public. These private and public investments are an expression of faith and hope over history because so few companies perform like Red Hat did. But, if HashiCorp negotiates the future quarters well, and rides the technology waves, it could grow faster than Red Hat did, and it might even reach profitability at the same level.

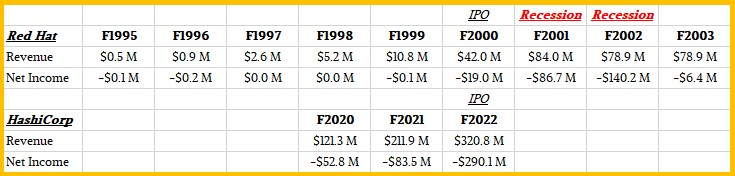

Here is how the two companies stack up in their fiscal years (which ended in January for both companies), centered on their initial public offering years:

Red Hat went public in July 1999 and raised $96 million in cash, and within a few months its market capitalization went nuts, kissing $20 billion in the frenzy of the Dot Com Boom, and it quickly fell back down to earth and had to earn its way back to that level, which it did not reach again until 2017.

When HashiCorp went public last December, it had 1,650 employees and around 2,400 customers, and raised a much more impressive $1.22 billion in cash, which it has in the bank and which it will burn as it tries to take the company and its Hashi Stack to the next stage. The company currently has a market capitalization of $5.6 billion, but it peaked at $13.3 billion a few weeks after the IPO.

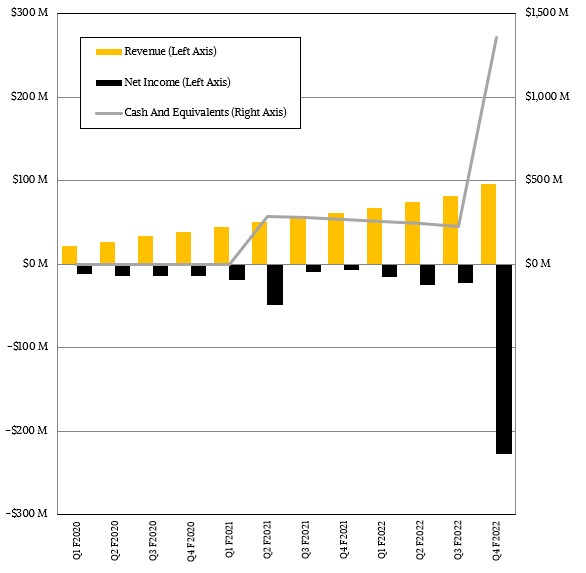

The numbers at this stage of any company’s history are not particularly pretty, but they are unavoidable. Here is the quarterly breakdown for the past three fiscal years – all of the data Wall Street has on HashiCorp, since it was less generous with historical data than Red Hat was back in 1999. HashiCorp gave out three years of quarterly data and Red Hat gave out six years of annual data. It is debatable which is more valuable. (Six years of quarterly data would be best, eh?) In any event, take a look:

With the IPO done and all that money in the bank, HashiCorp has pulled out the stops on the sales, marketing, research, and development spending. In the fourth quarter of fiscal 2022 ended in January, HashiCorp brought in $96.5 million in revenues (up 56.1 percent), and it had $1.36 billion in cash in the bank – the IPO money plus the cash it had leftover from five rounds of venture funding that brought in a combined $349.2 million. But it blew through enough cash to post a $227.7 million net loss, which was more than 10X the loss in Q3 F2022 ended in October 2021.

A year and a half of spending like that and all that money in the HashiCorp bank accounts will be gone.

The reason the loss was so large in fiscal Q4 is that HashiCorp recognized $196 million in historical stock-based compensation, and in future quarters the stock-based compensation will be a lot lower. For instance, it is projected to be on the order of $50 million in the first quarter of fiscal 2023 ending in April. We still think, as was the case with Red Hat back then and other fast-growing startups like Nutanix and Pure Storage, just to pick two, HashiCorp will have some losses in the coming year or two as it tries to expand its customer base to boost both revenues and profits.

What HashiCorp is banking on – and which is a credible argument technically and which we covered last June in our analysis of the Hashi Stack – is that the commercial-grade Kubernetes stacks are too complex and expensive and that HashiStack can do the same kind of cloud-native, containerized software platform at scale with a whole lot less grief.

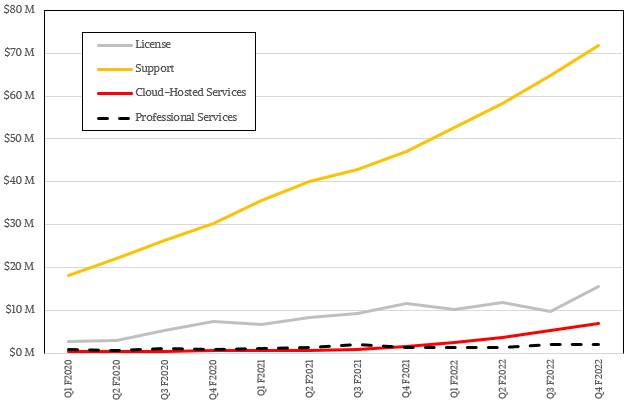

But the HashiCorp product lines are diverse and growing, and one can’t help but be optimistic that we may be seeing another technically sound platform get its financial footing. Here is how the product lines at HashiCorp have faired:

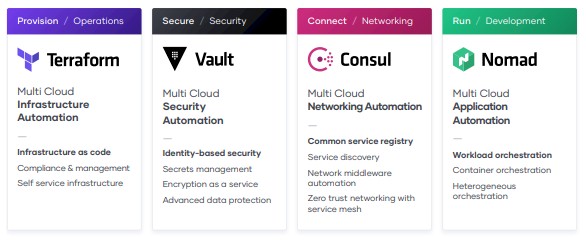

There are many different components of the Hashi Stack, but here are the core ones, and with well over 100 million downloads of these tools, converting this base to enterprise support, while difficult, should result in steady growth in the years ahead. And as companies look at Hashi Stack and compare it to the Red Hat OpenShift stack, we suspect that Hashi Stack will be able to hold its own again Big Blue and Red Hat when it comes to features, scale, and pricing. (We aim to start analyzing this more fully.)

Terraform alone makes HashiCorp worth billions of dollars, considering its popularity and the richness of its functions. But it is the exponential curve HashiCorp is on — and the immensity of the total addressable market that HashiCorp is chasing — that makes this company interesting to watch. It is a test of sorts that completely new ideas that are not from an HPC center or a hyperscaler or a big cloud builder, but by some nerds who read that same Google papers and were inspired to do it their way, can survive and maybe even thrive in the 21st century IT market.

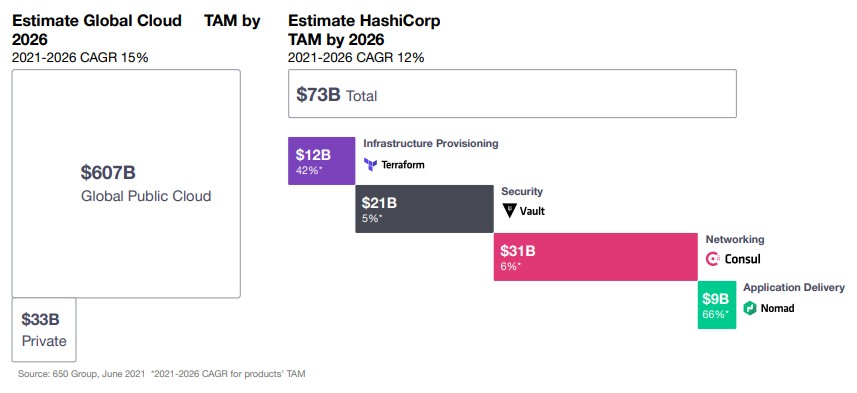

Here is the total addressable market that HashiCorp is chasing with its core four products:

There is plenty of room for OpenShift and other Kubernetes implementations to fight it out with Hashi Stack – and vice versa. HashiCorp ended the January quarter with 2,715 customers, almost double the 1,473 it had in the year ago period, and 655 of those customers have annual recurring revenue in excess of $100,000 per year and 72 of them spend more than $1 million a year. The company has $452.2 million in contracted licenses and support revenues – what is called remaining performance obligations, or RPOs, by the bean counters – on the books, and that grew by 58 percent year on year in fiscal Q4. The strategy is one we have all seen a zillion times: Land, Expand, Extend. Which means land with one product, expand use cases, and extend to cross-sell other products.

The company’s hosted HashiCorp Cloud Platform grew revenues by 4.5X in the quarter (to $6.9 million), and there is no reason to believe that as has happened with other software suppliers, a large number of customers will just use the hosted, cloud version and run it across a number of public clouds and either never have a datacenter or get rid of one.

It is going to be very interesting to watch how this all unfolds over the next decade. Or two.

Terraform is better monetized and offered outside HashiCorp, terrraform cloud alternatives are way better. This could be another Docker. Nomad is an alternative to Kubernetes but the winner has already been selected and companies will not take risks selecting the one that has not community and industry support. Other components of the stack are great but open source versions are good enough and very few will need support or paid services.