Once Dell spun out VMware on Wall Street, it was only a matter of time before someone would put together enough money to acquire it.

A year ago, we mused about Intel being the logical buyer of VMware once Pat Gelsinger left the top job at VMware to return to his chip roots at Intel, and we still think that a good case could be made for Intel to own the virtualization layer that runs atop physical chips for compute, storage, and networking. And when it was clear that Intel did not have enough money or credit to build one foundry, much less shell out enough cash to build three of them so it could take control of VMware. So forget that.

AMD was in the middle of eating Xilinx for what turned out to be $49 billion last year and into early 2022, so it could not eat anything as large as VMware. But with a stretch from some rich friends on Wall Street, maybe AMD could have pulled a VMware deal off.

We always thought that Nvidia’s acquisition of Arm Holdings was going to be a tough sell to antitrust regulators because so many chip makers inside the datacenter and outside of it want the Arm architecture to remain absolutely neutral – it’s the only way Softbank was allowed to acquire Arm Holdings. We nonetheless took Jensen Huang, the co-founder and chief executive officer of Nvidia, at his word that he wanted to buy Arm to grow it and protect it, and to adopt its distribution model for all of Nvidia’s chippery.

And when that Arm Holdings deal looked moot last summer, and when Nvidia was forging tighter and tighter links with VMware, we suggested that maybe Nvidia should buy VMware and control an entire HPC and AI software stack, from the hypervisor up and from the server node out across the datacenter. (We also suggested recently that Nvidia complete the set by acquiring SUSE Linux so it would have its own Linux and Kubernetes distribution.) Such a deal would give Nvidia access to over 300,000 enterprise customers and a vast legacy installed base of somewhere north of 100 million virtual machines from which to print money.

But, alas, Nvidia was distracted.

Hock Tan, the founder of Avago, which bought chip maker Broadcom for $37 billion in May 2015 and took its name, is not distracted.

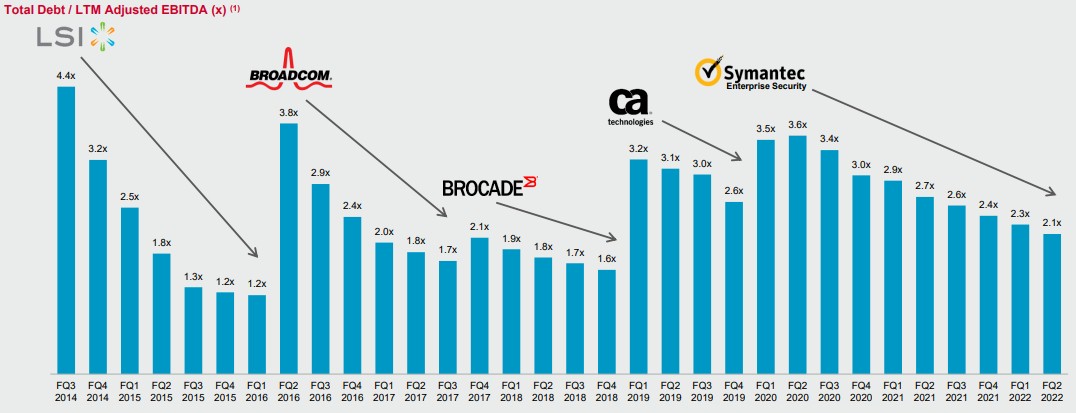

And Tan is legendary for making expensive acquisitions, cutting costs relentlessly, and making them pay for themselves. And Tan wants a bigger and more distributed software business than the Symantec security and CA systems management businesses it has spent a fortune on and still squeezed a lot of profit from. This chart is illustrative at just how good Tan is at building and expanding a conglomerate:

As long as there is cheap money, that is. And the cheap money is running out, fast, and so there is no better time to line up $32 billion in cash from a network of banks, blow a bunch of cash and stock, and assume $8 billion in debt from VMware and take a run at the world’s virtualization juggernaut for $61 billion.

(We are not going to get into the entire history of Avago/Broadcom here; you can read all about it there.)

Prior to rumors about the VMware deal hitting Wall Street on Monday, VMware had a market capitalization of around $40 billion plus $3.63 billion in cash and $12.67 billion in long-term debt, against $12.85 billion revenue and a net income of $1.82 billion for fiscal 2022 ended in January. Revenues are still growing, but earnings are not. And this is something that Tan knows how to fix. Here come the software licensing and support price increases and here comes the internal cost cutting and operating synergies from getting rid of VMware back office functions. But it is more than that.

In a presentation to Wall Street announcing the deal, Tan said that the plan is to ride up the workload expansion VMware has been seeing consistently since entering the datacenter back in the 2002 when it launched the GSX Server hypervisor. But Tan is also going to focus VMware’s research and development where it is “uniquely positioned to innovate and drive customer success” as well as focus sales and marketing efforts across the Broadcom portfolio on that vast VMware enterprise base. This is why Tan sold off the nascent but technically strong “Vulcan” Arm server chip business of Broadcom to Cavium, which revived the Vulcan effort as ThunderX2 and which was also essentially shut down after Marvell acquired Cavium and then saw there was not all that much money in it after all.

The net-net is this. In the fiscal year just ended, VMware had $4.7 billion in earnings before income taxes, depreciation, and amortization. (That’s at a non-GAAP level, which is a generous accounting of profits.) Tan thinks Broadcom can boost that VMware middle line to $8.5 billion.

The obvious question is why VMware can’t do that itself. It’s simple. Everyone knows everyone at VMware, and it is hard to cut people with a long history at a company. And a lot of that increased profit will come from the elimination of back office functions at VMware. That’s how Computer Associates build its mainframe and Unix conglomerate, and it is not a coincidence that CA was eaten by Broadcom as its first software acquisition. Tan learned much from CA founder Charles Wang, certainly indirectly before Broadcom paid $18.9 billion to buy CA in November 2018, if not directly before Wang passed away, then indirectly over Wang’s long and dramatic career of build Computer Associates. (Wang died a month before the Broadcom deal was announced.)

But as that chart shows above, Tan knows how to leverage Avago to buy something and then de-lever the embiggened Avago (now Broadcom) so it can go out and acquire again. Free cash flow in fiscal 2015, just after the Broadcom deal was done, was $1.7 billion and dividends per share were $1.94. In fiscal 2021, free cash flow for the Broadcom conglomerate was $13.3 billion and dividends per share stood at $14.40, and Tan expects it to go to $16,40 per share this year.

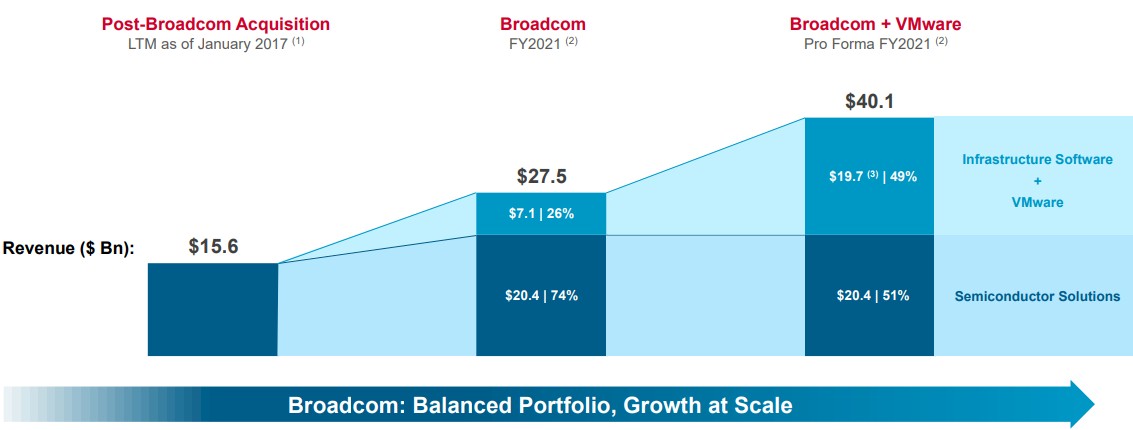

This chart gives you a sense of how Broadcom has changed over the years:

The last twelve months (LTM) of revenue in January 2017 after the Broadcom acquisition by Avago was complete, and again with Avago taking the Broadcom name, came to $15.6 billion. At the end of fiscal 2021 ended in October, Broadcom had nearly doubled in size, with $20.4 billion in chip, board, and now system sales. The company’s Symantec and CA software businesses accounted for $7.1 billion in sales, and are considerably more profitable than the hardware side of the house, as you might expect. Operating margins are in the 70 percent, because there is not a lot of selling going on. Why?

The secret about that Broadcom software business is that about half of its revenues are coming from IBM mainframe shops, and a very small number of accounts – around 500 according to Tom Krause, formerly chief financial officer at Broadcom and now the head of its Software Group – drive a big portion of that software revenue. If you add in VMware revenues through October 2021 to the Broadcom numbers, you get the stacked bar on the right, and half of the embiggened Broadcom is now software and half is hardware. And now, Krause explained on the call with Wall Street, Broadcom will have 1,500 large global accounts to take care of and cross sell into, and the other 299,000 VMware accounts will be sold into by the resellers and OEMs with development and support back at VMware.

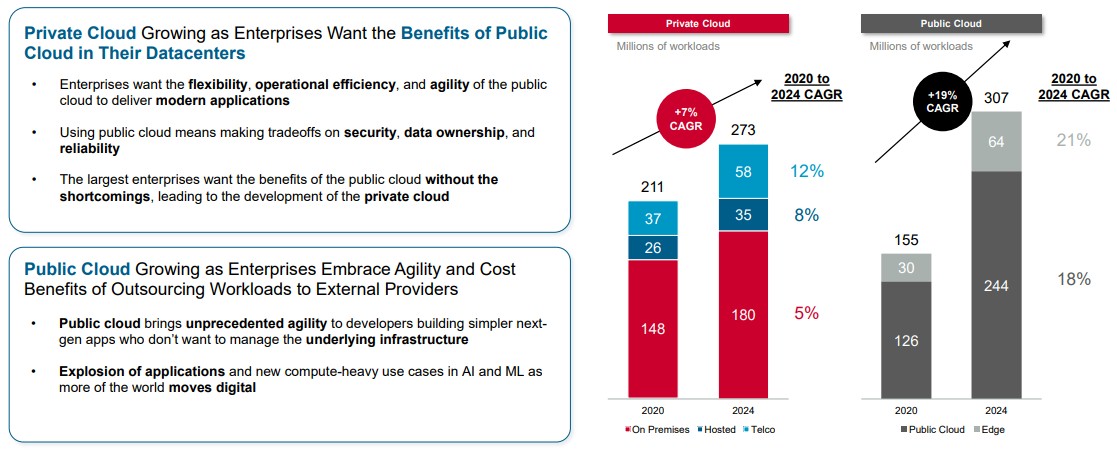

Here is what Broadcom is betting on:

While containers are all the rage among the hyperscalers and cloud builders and all of the cool kids who emulate them, in the enterprise, the VMware ESXi virtual machine is the unit of software consumption still, and companies have spent a fortune – and will continue to spend a fortune – on maintaining their “21st century software mainframe” comprised of ESXi, vSAN virtual SAN storage, and NSX virtual networking – something that former VMware CEO Paul Maritz was explaining was the goal way back in March 2009 when the world economy was also shaky and made the conditions that enhanced VMware’s success.

VMware is a little bit different now. Its software has expanded to cover all aspects of the enterprise datacenter, its customer base is large, and that customer base is as risk averse as it has ever been. And so it is a pretty safe bet that most VMware customers are going to stay put and the number of VMs and workloads they will have managed on top of the VMware stack will keep increasingly moderately in the coming years as it has in the past decade. And being able to deploy VMware’s software infrastructure atop the public clouds gives it a hybrid story that can rival that which IBM is pushing in the wake of its $34 billion Red Hat acquisition in October 2018.

If Broadcom was still based in Singapore, as it was just after the Broadcom deal, there might be some US national security issues to the VMware deal, but Broadcom moved its HQ to San Jose years ago. Regulators might hem and haw, but the reality is that no one feels proprietary about VMware the way its licensees and the government of the United Kingdom did about Arm. If Softbank wasn’t a conglomerate based in Japan with all kinds of diverse holdings, the original Arm deal would not have gone through regulators, either.

The interesting bit is whether or not Michael Dell, who has a 40.2 percent stack in VMware, wants to be a large shareholder in Broadcom. The price that Broadcom is paying for VMware is around a 40 percent premium, so it is hard to imagine that Dell, the man, is not pleased about “unlocking this shareholder value,” as they often say on Wall Street. And Dell, the man, put his stamp of approval on the deal when it was announced and so did his long-time private equity piggy bank, Silver Lake, which owns 10.2 percent.

So if someone wants to take advantage of the 40-day “go shop” option that VMware has to get a better deal, they better bring some rich friends. This deal is already done with those two votes, since Broadcom has 50.2 percent of the shares. The way the deal is structured, by the way, half of VMware will be bought with cash and half with Broadcom stock, and the deal will be prorated to make it all balance out. So maybe Dell and Silver Lake are cashing out and everyone else who owns VMware stock is going to get Broadcom stock and that’s it.

As for that go shop provision, there are not that many people who want to buy VMware. As we said, we can make a case for either Intel or Nvidia. Broadcom is also a logical choice. Cisco Systems could do it, but it is too distracted trying to pick fights with Broadcom in the merchant silicon market for datacenter switching and routing. Dell, the company, owned it and spun it out, and Hewlett Packard Enterprise cannot afford VMware. Lenovo and Inspur would never be allowed to buy VMware by US regulators. Amazon Web Services, Google, and Microsoft could all do such a deal and you could make a case for them embracing VMware to help move all those ESXi VMs to a substrate in the cloud in addition to on premises.

Broadcom paid a heavy premium for VMware to make that go shop provision a formality rather than an actual possibility, and it wants to build a balanced conglomerate with hardware and software, and it has no plan to now break Broadcom into a hardware business and a software business.

“We see a lot of benefits in putting all of these various franchises we have – hardware and software – under one umbrella,” Tan explained on the call with Wall Street. “Think of it this way. Merchant silicon is driving a trend. The old model is you sell a black box hardware and software system to a customer in the IT department. That’s what you did in the past. If something goes wrong, you ask for support and you scream for help because you don’t know what is going on inside the thing. We are creating a model of disaggregation between hardware and software. We still may not know a lot about systems, but we sure know the technology that enables systems, whether they are switches, routers, compute, storage. Broadcom has a model of disaggregating hardware and software, but combined, we are stronger than if these were divided.”

In other words, just because your hardware and software are disaggregated doesn’t mean you can’t sell both kinds of wares.

“The way the deal is structured, by the way, half of VMware will be bought with cash and half with Broadcom stock, and the deal will be prorated to make it all balance out. So maybe Dell and Silver Lake are cashing out and everyone else who owns VMware stock is going to get Broadcom stock and that’s it.” Uh no. That’s not the way it works. All shareholders are equal when it comes to proration. If the majority of shareholders elects to be paid in cash or in shares, all shareholders will end up getting paid out in 50% cash and 50% shares, including M.Dell.