Speaking in generalities across any aspect of history is always risky, but that is what the job of history is.

The first wave of open source software in the enterprise in the 1960s through the 1980s was largely academic, and it wasn’t until the second wave of open source hit – and hit hard – as the first wave of the commercialization of the Internet took hold in the late 1990s that there was a chance that someone might actually figure out how to make money selling something to enterprises as they adopted open source software.

Whatever that something was, the one thing it was not was obvious.

Red Hat, which had first mover status in the enterprise, figured it out, packaging a complete server stack atop the Linux kernel and selling subscriptions for the packaging and ongoing support of that stack. And while Red Hat will never make as much money in systems software as Oracle or Microsoft, it certainly has been a boon to IBM’s software and consulting businesses since the latter decided to pay $34 billion to acquire the former in October 2018.

The deal closed in 2019, and since that time, IBM has largely left Red Hat alone and has been happy that it has a true hybrid cloud story to tell and that it has a growing systems software business based on open source to counterbalance its somewhat shrinking proprietary hardware and closed source systems software businesses.

The Red Hat subscription business is not growing as strongly as it did a few years ago, but still much faster than IBM’s overall growth, and importantly, IBM’s consulting business relating to the Red Hat platform – we presume mostly for the OpenShift Kubernetes container platform – has exploded.

In the quarter ended in September, sales at Red Hat grew by 12 percent to just a tad over $1.5 billion, and were up 18 percent when gauged in the local currencies in the 140 countries where IBM does business outside of the United States, where it is headquartered. We reckon in our model of IBM that about 70 percent of the subscription and support revenue at Red Hat is for core systems software – Red Hat Enterprise Linux operating systems, KVM server virtualization, OpenShift container platform and OpenStack cloud platform, and Gluster and Ceph storage. The rest is high-level middleware (like the JBoss application server) or various tools or desktop variants of Linux.

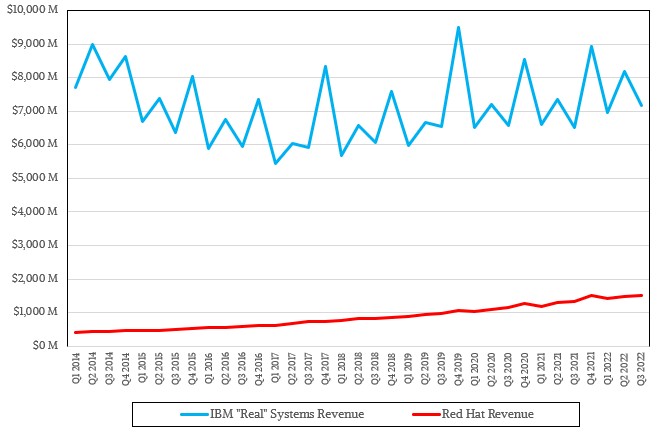

The underlying IBM systems business, thanks to upgrade cycles for systems based on its “Cirrus” Power10 processors used in the Power Systems line, and the “Telum” z16 processors used in its System z mainframe line, also grew by 9.8 percent in the quarter, to $6.14 billion. Add it all up, and the “real” IBM systems business, according to our estimates, accounted for $7.19 billion in sales in Q3 2022, up 10.1 percent.

In the chart above, you can see how IBM’s sales of supercomputers and enterprise servers based on the Power9 processors as well as the z15 CPUs in the System z line in 2018 bent the overall revenue stream up a bit. But backing out of capability-class supercomputing (which was not particularly profitable for IBM) would made for a further declining systems business. The coronavirus pandemic helped goose IBM’s systems sales some, of course. But it is the addition of Red Hat that is really pushing IBM’s overall “real” systems business up, and in fact, had it not been for Red Hat, IBM’s core systems business would have been averaging somewhere around $5 billion a quarter, with some quarters being below $4 billion.

This hybrid systems strategy is precisely what we said the plan was from the beginning, and why Big Blue spent so heavily to acquire Red Hat. And our projections were for IBM’s overall core systems business to grow back to levels that Big Blue has not seen since 2014 – when it was running at $7.7 billion to $9 billion a quarter. Our forecast said this would happen by 2025, and IBM is on track perfectly to make us right. (Whew!)

But that is not the only Red Hat effect, as you might imagine. There is a huge consulting business at IBM, and Red Hat is a big part of it, which we learned concretely in the call with Wall Street analysts going over the IBM financial results for Q3. Jim Kavanaugh, IBM’s chief financial officer, said on the call that since the Red Hat deal has closed, IBM has done close to 1,400 consulting engagements with customers and that this has yielded $6.6 billion in bookings so far. The Red Hat consulting practice is growing at “double digits,” and was nascent before the deal was inked.

Our best guess is that bookings for these Red Hat consulting engagements are running at about $750 million a quarter, about 10X larger than it was before the Red Hat was bought by IBM. Heaven only knows when the revenues get recognized, but certainly not all at once.

“We would not have gotten that revenue and that book of business if we had not done that acquisition,” Arvind Krishna, IBM’s chief executive officer and the architect of the Red Hat deal, declared point blank on the call. And Krishna is absolutely right.

But don’t get the wrong idea. For IBM, hybrid is the next platform, not Red Hat. There will come a day, perhaps, when the Red Hat platform contributes as much revenue – and maybe even the same profit – as the two enterprise system families that have defined IBM for most of its history. But rest assured: When we are all dead and buried, there will still be mainframes and Power Systems running mission critical, back-end systems deep in the bowels of tens of thousands of companies worldwide. As it is, there are about 165,000 of them today, and they spend a premium price for a premium product that they know how to make sit up and bark as well as any hyperscaler knows how to make a cluster hum. At the prices IBM charges for its systems – particularly mainframes – they have to run them at 99.5 percent utilization. And with mainframes, they do, which is an amazing thing you never hear about RISC/Unix servers or clusters.

There may not be a huge amount of direct synergy between the IBM proprietary systems and the Red Hat stack, but they are certainly mutually dependent. IBM needs to make money in both.

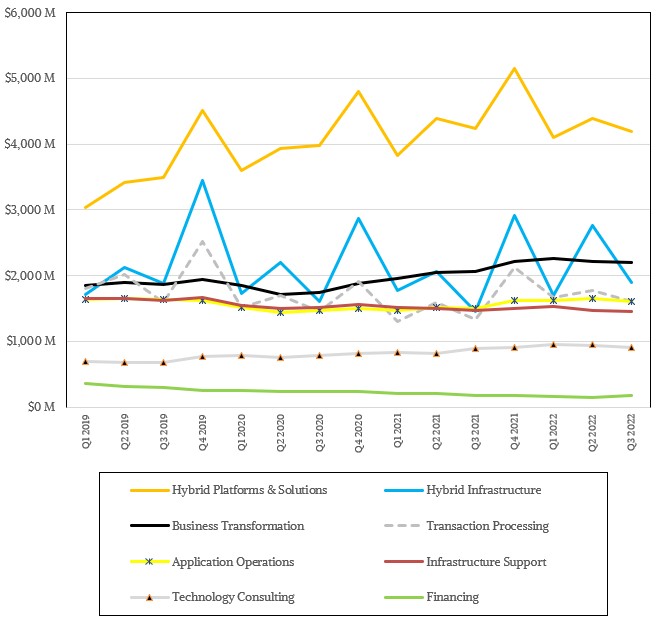

In the third quarter, IBM’s Infrastructure group posted sales of $3.35 billion, up 14.8 percent, with a gross profit of $1.7 billion (50.8 percent of sales, and up 10.5 percent from the prior quarter) and a pre-tax income of $280 million, flat year on year. Sales of servers, storage, and operating system licenses came in at $1.89 billion (we model this, IBM doesn’t reveal it), which we think is an increase of 30.1 percent. Within this, System z sales rose 98 percent (meaning almost doubled) at constant currency, and sales of Power Systems plus storage products grew by 21 percent together.

Sales of capacity to the Kyndryl managed services spinoff represented around 9 points of the overall 23 points of growth (again at constant currency) that the Infrastructure group had in Q3 2022, and Kyndryl similar represented 11 points of the 41 points of growth (against at constant currency) for what IBM calls Hybrid Infrastructure (meaning all servers and storage together).

Infrastructure support was down a fraction of a point to $1.46 billion as reported, and was up 5 percent at constant currency. This is still a relatively healthy business, even if it is expensive to maintain, and it does provide IBM enough profits to keep playing the game and generate free cash flow from all of the other database and middleware software and consulting services that this legacy platform duo generate year in and year out.

For now, this is all working about as well as IBM could have expected and about as well as the company needs to keep telling – and selling – its hybrid cloud story to enterprises.

All told, IBM had $14.11 billion in sales, up 6.46 percent, and had a gross profit of $7.43 billion, up 4.6 percent. The company had to book a $5.76 billion charge for offloading some of its pension liabilities to a third party, and offset this with a $1.29 billion income tax gain, and thus posted a net loss of $3.21 billion.

Be the first to comment