The central bankers of the world want to curb inflation by putting a serious crimp in demand, and it looks like they may get what they want – sort of – in 2023 when it comes to datacenter infrastructure.

The latest forecasts out of market researcher IDC certainly back up what has become the expectation of many. And as you know, sentiment is a kind of self-fulfilling prophecy in an economy: We are collectively what we believe are going to do, and there are vicious and virtuous feedback loops that can be created that can make a tough situation worse than it might otherwise be.

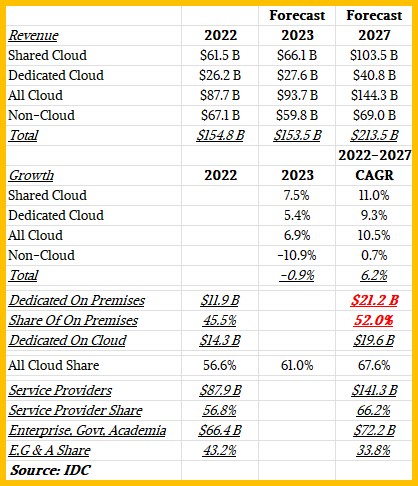

IDC just put out its quarterly cloud server and storage spending assessments for 2022 and its forecast for both 2023 and out into 2027, and perhaps the most important bits of data have to do with spending for 2023. So we will cut right to that in this summary chart:

While the statement put out by IDC doesn’t give the full spending number for datacenter servers and storage for 2023, we did the math on what it put out in the table above and will tell you. Overall spending worldwide is expected to decline by nine-tenths of a point to $153.5 billion. And all of that decline is going to be due to a forecasted 10.9 percent decline in spending for on-premises, non-cloud gear. Spending on cloud capacity, whether it is running in one of the big clouds or regional or niche service providers, is expected to grow by 6.9 percent to $93.7 billion. That sounds good, but it is a far cry from the 19.4 percent growth in shared and dedicated cloud spending. Shared cloud capacity – what many call public cloud but we have not for years because Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud are not public utilities, but private enterprises – is expected to bring in $66.1 billion in 2023, up 7.5 percent from 2025’s spending levels. Dedicated cloud – which can mean outposts of the big clouds that run on co-location facilities or corporate datacenters – is expected to grow modestly, up 5.4 percent, this year to $27.6 billion in sales.

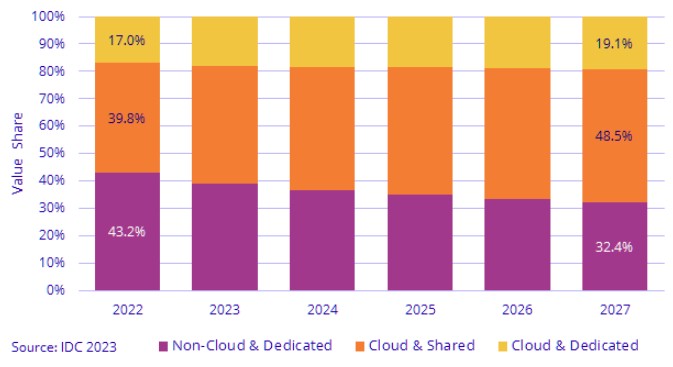

We have pointed out that recessions do not cause IT transitions, but rather they accelerate them, and this will be the case now with datacenter infrastructure if the forecasts made by IDC between 2022 and 2027 pan out:

By the end of the forecast period, more than two-thirds of the revenues being spent on compute and storage capacity by end user companies will be for shared or dedicated cloud infrastructure services, and less than one-third will be for legacy non-cloud infrastructure. (As we have pointed out before, it is not clear how IDC draws these lines between cloud and non-cloud. An IBM mainframe can have thousands of logical partitions and can have metered pricing for hardware and software – these question is how many companies actually do this, we presume.)

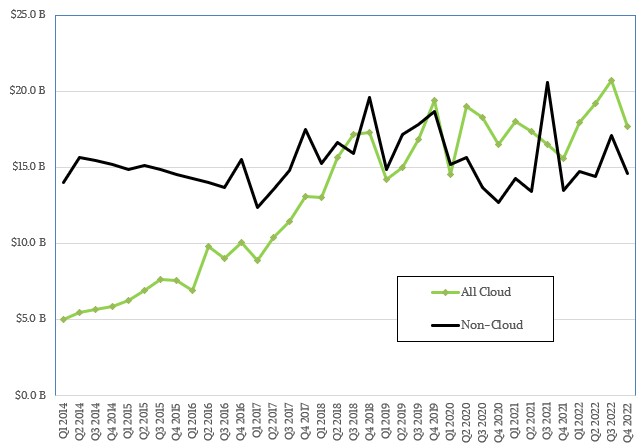

All things considered, 2022 was a pretty good year for datacenter infrastructure, and it may be the last good one we see for a while if the global economy does not respond effectively to interest rate shocks, bank turmoil, and political upheavals in hotspots around the world. We remain hopeful, but as Alanis Morrisette correctly pointed out, the past few years of IT spending have been a jagged little pill:

If you squint a little on that black line representing Non-Cloud infrastructure spending, you can see the IBM System z mainframe cycle and some wigglies for the Power Systems Power8, Power9, and Power10 cycles. You will also note that even though this line is very jaggy, it has averaged just a little north of $15 billion per quarter for the dataset that IDC has put out to the public. Non-Cloud server and storage spending is essentially flat for the past decade, on average, and many would think, based on the slice of the server and storage bars in the chart above, that it was in decline. It was not. Cloud is just growing, so it makes it look like Non-Cloud is in decline.

And on the green and dotted All Cloud line – which remember is cloud consumption by customers and dedicated cloud infrastructure parked on premises or in co-los, not spending on IT gear by the big clouds themselves to supply these services – you can see hints of the inside upgrade cycles that Intel and AMD give to hyperscaler and cloud customers as well as the normal tendency to buy IT infrastructure at the end of a budget year. The third and fourth quarters of one year do a lot better than the first and second quarters of that same year.

At this point, we would have expected for a fairly smooth line for All Cloud server and storage spending. But set against the ever-increasing need for compute and storage to do more workloads – and more complex ones – is also the maturity cycle for cloud computing, where companies get better at buying and managing capacity. Luckily, there are always newbies coming into the cloud fold – at least for a while yet, anyway.

Be the first to comment