If Big Blue is going to talk the hybrid cloud and AI talk, as it seems to do incessantly, then the company has to walk it. And perhaps the most interesting thing that was said as part of the company’s discussion of its first quarter 2023 financial results was its revelation of its own internal efforts to embrace containerized applications that run in a cloud and to use AI to automate operations as well as transactions to cut costs.

“Think of IBM as client zero,” explained James Kavanaugh, chief financial officer at IBM. “We are driving G&A efficiencies by reimagining and transforming the way we work. This includes optimizing our infrastructure and application environments as well as redesigning our end-to-end business processes.”

This reminds us of the time when IBM not only desired to be the biggest seller of systems and consulting services for SAP’s R/3 ERP suite, but also SAP’s biggest customer, replacing all of its myriad and disparate homegrown manufacturing, distribution, and back office applications ahead of the Y2K date change. That two-digit date problem in legacy applications was a boon for SAP and its systems partners, and the transformation of the SAP portfolio continues apace at IBM.

As IBM said last year, more than 300 SAP instances running on over 500 Power Systems servers, covering the operations of over 1,000 legally distinct entities within Big Blue, spread across 120 countries, are all being converted to the SAP S/4HANA application suite running on the SAP HANA in-memory database atop Red Hat Enterprise Linux running on the IBM Cloud. The S/4HANA applications and HANA databases, the latter of which will total over 375 TB of memory, are presumably still going to be running on IBM’s Power Systems in the cloud, presumably containerized on the OpenShift Kubernetes container controller and presumably not on the X86 iron that dominates Big Blue’s server fleet underpinning the cloud service it sells to enterprises.

The point is, IBM is also getting around to walking the SAP HANA talk, too, which gives its 38,000 SAP consultants a very valid talking point to its potential enterprise customers. But back to hybrid cloud and AI walking that IBM is now doing.

“Across IBM’s IT environment, we are realizing the value of hybrid cloud,” Kavanaugh continued. “We reduced the average cost of running an application by 90 percent by moving from a legacy datacenter environment to a hybrid cloud environment running on Red Hat OpenShift. We have been simplifying our application environment. By standardizing global processes and applying AIOps, we are reducing our application portfolio by more than 35 percent. We have automated over 24 million transactions with RPA [short for Robotic Process Automation], avoiding hundreds of thousands of manual tasks and eliminating the risk of human error. And we are deploying AI at scale to re-engineer our business processes. We are doing that in areas like HR and talent, finance, and end-to-end processes like quote to cash and source to pay. For example, in HR, we now handle 94 percent of our company-wide HR inquiries with our AskHR digital system, speeding up the completion of many HR tasks by up to 75 percent. These productivity initiatives free up spending for reinvestment and contribute to margin expansion.”

Workload balancing, as IBM did in the quarter, contributes to this over the long term but there is a hit in the short term. IBM expected to take a $300 million charge for layoffs in the first quarter ended in March, and managed to get $260 million of that done, with another $40 million to go now in the second quarter. And those charges had a dampening effect on IBM’s profits in Q1.

In the March quarter, IBM revenues rose by four-tenths of a point to $14.25 billion, and gross profits were up by 2.4 percent to $7.51 billion. Even with that $260 million in charges, IBM was able to push up net income by 26.5 percent to $927 million, which is 6.5 percent of revenues, which is about average for Big Blue.

Here is the rundown of IBM by its groups and divisions:

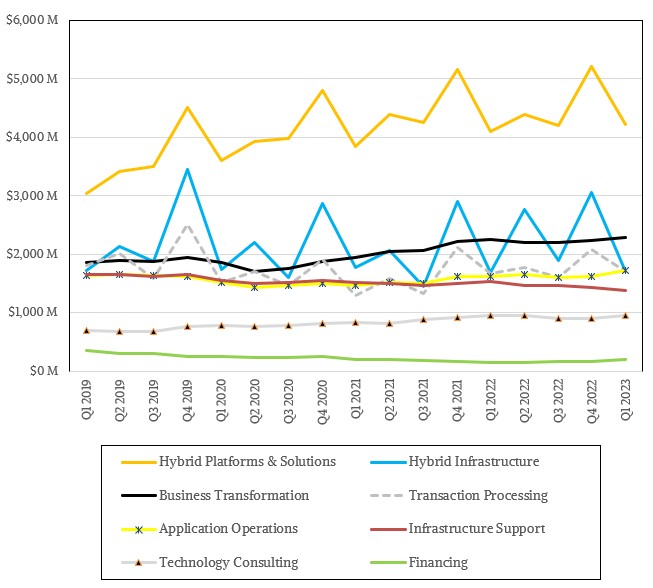

And for those of you who like to analyze visually, here is a chart that casts IBM’s current financial presentation of groups and divisions back to Q1 2019:

When you cut to the chase scene, IBM has $17 billion in cash, expects to generate $10.5 billion in free cash flow in 2023, and has a whopping $58 billion in debt, thanks in part to the way it finances hardware, software, and services in its channel and on behalf of end users as well as the remaining debt hangover from the $34 billion acquisition of Red Hat, which was completed in July 2019.

The effect of that Red Hat acquisition on IBM’s psyche has been transformative because it gives Big Blue a whole new story to tell as well as a dramatically different line of products to sell. And you can see how a rebound in System z and Power Systems sales coupled to the addition of Red Hat to the books in the second half of 2019 have lifted IBM’s “real” systems business, just as we had said it would five years ago when the deal was first announced:

That said, Red Hat’s growth has been slowing since that deal was completed, when it was growing its business at a 20 percent or so rate, and many had hoped, given the vast opportunity ahead for containers and Linux, it would continue and thereby help payback that $34 billion all the more fast. In the current quarter, Red Hat grew by 11 percent at constant currency but only at 8 percent as reported, which frankly is all that matters unless you are trying to console yourself because of the strength of the US dollar. By out math, that works out to $1.52 billion for Red Hat in Q1 2023, and on a trailing twelve month basis, Red Hat has $6.17 billion in sales, up 11 percent (the real 11 percent, not the constant currency one). This is still the fastest growing business for IBM, but it is nothing like the more than 50 percent of revenues it gets largely on an annuity-like rental and subscription basis for its System z mainframe platforms installed at a representative portion of the Global 10,000 worldwide. (Probably on the order of 6,000 unique customers.) That said, OpenShift now is driving an annual recurring revenue of $1 billion, and there is no good reason that it cannot be 2X, 3X, or even 4X of that over the longest of hauls in our opinion.

IBM does not report its systems sales by architecture, but its Infrastructure group posted sales of $3.1 billion in the quarter, down 3.8 percent and had a pre-tax income of $216 million (7 percent of sales), up 8.5 percent. Hybrid Infrastructure, by which IBM means all systems and storage, rose by 1 percent to $1.71 billion, and Infrastructure Support fell by 9.1 percent to $1.39 billion. Sales of what IBM calls Distributed Infrastructure, which means Power Systems iron and all of its tape, disk, and flash storage lumped together, was flat year-on-year, but System z mainframe sales rose by 11 percent. These are, once again, figures given in, constant currency.

IBM’s “real” systems business is hard to reckon, but we take a stab at it every quarter, and reckon this time around it accounted for $5.95 billion in sales, down a half point from the year ago period. On a trailing twelve month basis, this “real” systems business drove $27.2 billion in sales, up 5.1 percent, according to our model. These figures do not include the systems parts of the Red Hat business, which we reckon accounts for about 70 percent of Red Hat revenue. If you add in the Red Hat datacenter and edge business, then you are talking about $31.52 billion in “real” systems sales for Big Blue in the trailing twelve months, up 5.9 percent. This estimate includes servers, storage, systems software but not middleware and databases, and a chunk of technical support services and financing that we think is attributed to IBM’s own systems. We know it is witchcraft, and it is meant to be illustrative, not definitive.

IBM could just tell Wall Street what is what, but that would be too easy.

Be the first to comment