Our choice of words in founding this publication nearly a decade ago were no accident. Throughout six decades of IT history, those who build and sell platforms wield technical power and have the best chance of extracting super-normal levels of profits from their customers.

That is as true of Google, Facebook, Microsoft, Apple, and others who provide consumer-facing applications as it has been of IBM in mainframes, Digital Equipment Corp with minicomputers, the Unix collective led by Sun Microsystems before and during the Dot Com boom, Intel as the general purpose platform provider for the Internet build out and Microsoft and Red Hat as the preferred software stacks atop that platform. And, of course, it is true of VMware, which makes hardware platforms malleable and more manageable through software and which drives up utilization on those hardware platforms.

The working title of this story was Everybody Tries To Take Advantage Of VMware, which was meant to convey the double entendre that we so love here at The Next Platform. One a year since we can remember – OK, since 2004 when the first VMworld conference was held – VMware interrupted one of the last weeks of summer vacation for our families and had us congregate in San Francisco and then eventually was moved up to The Show in Las Vegas and regaled us with all of the neat virtualization wizardry that was going to make the static hardware in the datacenter more like software.

These days, it is called VMware Explore, and chip maker Broadcom, which ate the ancient Computer Associates mainframe and Unix software conglomerate (known as CA Technologies, but we have longer memories than that) and the Symantec enterprise security software business because. . . er . . . it can, is trying to get final regulatory approval for the $61 billion acquisition of VMware that Broadcom announced in March 2022.

VMware, founded in 1998 and utterly transforming the enterprise datacenter, never got to be a public company in its own right, having been snapped up by an ascending storage maker EMC back in December 2003 for $625 million after six years of selling its ESXi X86 server hypervisor to enterprises, giving them mainframe-class virtualization and allowing them to skip server upgrade cycles in the wake of the Great Recession. This was when the X86 platform needed virtualization most, and VMware provided the one that was the best. Which is why the company grew like crazy and why Dell wanted to buy EMC, and therefore VMware, in December 2015 for $67 billion. Once Dell started to talk about spinning out VMware a couple of years ago to help pay down the debts from that deal, it was inevitable that VMware would be acquired by someone.

We pondered how Intel was a logical buyer for VMware, which made sense with Pat Gelsinger being chief executive officer at VMware at the time and with Intel needing a software revenue stream that was closely related to compute and networking. AMD was busy buying Xilinx for $49 billion at the time, so that wasn’t going to happen, and Nvidia was similarly distracted by its $40 billion deal (which did not close) to acquire Arm Holdings from Japanese IT conglomerate SoftBank (which is now getting ready to re-float Arm on the stock market, this time on the NASDAQ instead of the London Stock Exchange). When that Arm deal went south, we suggested that Nvidia, which had cash and stock valuation coming out of its ears, might buy VMware to gain access to its 300,000 enterprise customers.

Nvidia has a lot more cash today, and so does AMD, and both have plenty of market capitalization they could spend on such an acquisition, and neither is going to make a move to try to swoop in and best the deal that Broadcom founder Hock Tan is making to take over VMware. If Intel had $61 billion, it would have other things to do with it. Like build three foundries and try to get its chip manufacturing business uprighted. IBM spent all the cash it had in the world, and quite a bit of debt, to buy Red Hat for $34 billion in 2019, and is one of the big competitors, alongside Microsoft, to VMware.

AMD, Intel, and Nvidia have VMware right where they want it, constantly enhancing its ESXi server hypervisor and tools, its NSX virtual networking, and VSAN virtual storage, improving performance and security for CPUs and GPUs on premises and in the cloud, and keeping those 300,000 customers happy driving efficiencies and adding Kubernetes container extensions, AI frameworks and DPU support to that complete stack. If you boil down the announcements that VMware has made over the past several years, that’s it. The VMware stack is a complete platform that has achieved legacy status for its core virtualization and is a modern stack because of these extensions. By the way, just like the IBM System z mainframe, which is a platform that is decades older, is.

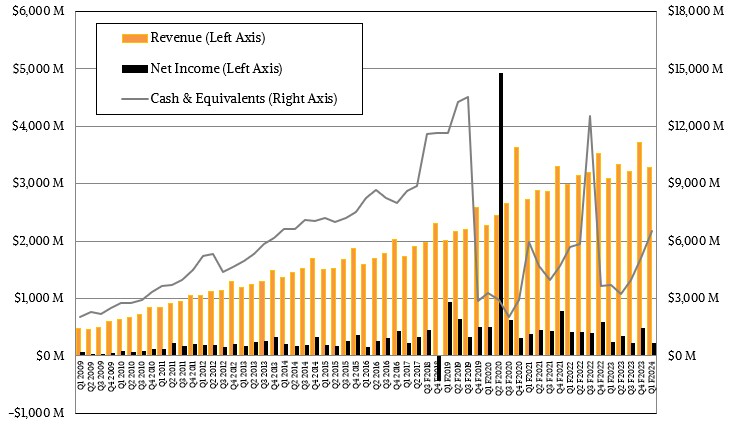

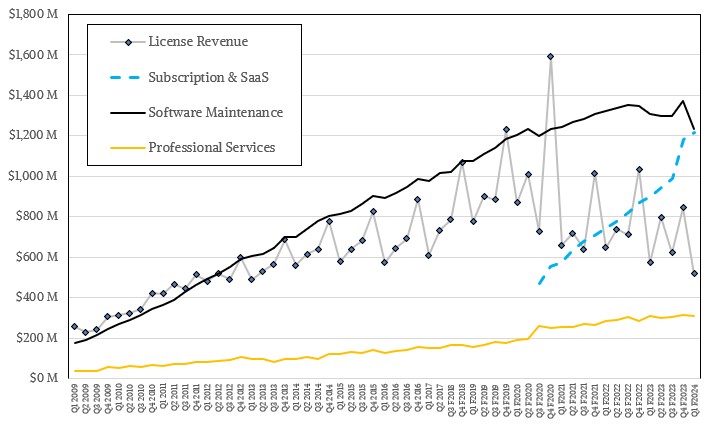

It doesn’t get better than this at this point in the development of VMware, which is why as VMware shifts from licensing to subscriptions its revenues are flattening and its profits are under pressure.

For now, pushing NSX and vSAN deeper into the core ESXi customer base of enterprise customers – which we have always thought was around 50,000 organizations worldwide – is key. Our guess – and we have to guess because VMware doesn’t talk about it this way – is that maybe a quarter to a third of these core customers have added NSX and vSAN to their virtual infrastructure. Making all three available on the clouds, which VMware has done in a bare metal fashion with Amazon Web Services and IBM, is important, as is increasing the telemetry and control for the “21st century software mainframe” that VMware set out to create a decade and a half ago now.

The fact remains, and what both Nvidia and Broadcom realize full well, is that the VMware stack is the infrastructure substrate that many enterprises have chosen, and it is how they provision and manage their clusters as well as how they package and deploy their applications. They are not going to change anytime soon, just like Unix systems persist and IBM mainframes persist running mission-critical databases and their applications to this day. IBM is the last of the Unix and mainframe suppliers, for all intents and purposes, and has maybe 5,000 unique mainframe shops and maybe 20,000 Power Systems-AIX shops. Many have huge Windows Server and Linux server fleets, too, running newer applications like Web infrastructure, data analytics, and now AI training and inference. VMware appears to be getting its share of that latter bit on premises and has tried many different tactics to address the cloud.

But its financials are under pressure. In the trailing twelve months ended in May this year, VMware’s revenues were $13.58 billion, up only 4.6 percent, and its net income just a tad under $1.3 billion, representing 9.6 percent of revenue and down 20.8 percent year on year.

VMware has a good business, and a reasonably steady business, and a software maintenance business that has grown steadily but which is under pressure as the company transitions to a subscription model.

Broadcom’s Tan is brilliant at making acquisitions and pushing up revenues while slashing costs to increase profits, and because Tan didn’t create these companies, it isn’t personal when the cuts come. It’s just business.

Many companies have this issue as they reach legacy status. Take Oracle, for example. It’s net margins for the trailing twelve months averaged around 25 percent in 2010 through 2017, took a big hit down to 10 percent in 2018, bounced back in 2019 and 2020, soared above 30 percent for a few quarters in 2021 during the coronavirus pandemic, and have been languishing between 10 percent and 20 percent since then. Oracle is investing heavily in its eponymous cloud, and that is part of the reason, but the other reason is that it has much more competition in databases and middleware than it ever had, and its rivals in application software – SAP, Microsoft, Saleforce, and a zillion SaaS players – are taking bites, too.

It is reasonable to assume that VMware could get back to somewhere around 20 percent – and even 25 percent – net margins, and we think that is exactly what Broadcom will do through a combination of price hikes (which are easier to hide in a monthly subscription) and cost cutting. Broadcom has to get that $61 billion back somehow when this deal gets done.

The date for EMC’s acquisition of VMware requires correction. December 2023 is in the future.

Fixed. I also got it founding date off by a decade. I dunno. The phone rang during that sentence.