Timing is a funny thing. The summer of 2006 when AMD bought GPU maker ATI Technologies for $5.6 billion and took on both Intel in CPUs and Nvidia in GPUs was the same summer when researchers first started figuring out how to offload single-precision floating point math operations from CPUs to Nvidia GPUs to try to accelerate HPC simulation and modeling workloads.

The timing was serendipitous, and it set AMD on a path to a second form of datacenter compute that, quite honestly, has been elusive to the company because it had such a big mess to clean up in the server CPU business after mothballing the Opteron server CPU line a few years after acquiring ATI. Under the guiding hand of Lisa Su, AMD not phoenixed a server CPU business in the Epyc line, which is now selling its fourth generation of chips and doing quite nicely despite a plain vanilla server recession – caused in part by the need to spend huge sums of money on AI servers – but it has been working in fits and starts to put together a credible lineup of Instinct GPUs, with their own architecture unique from its Radeon client GPUs, that can take on Nvidia in the datacenter and also hold at bay the swarm of startups peddling matrix math engines aimed at AI and sometimes HPC and analytics.

The rise of what used to be called the Radeon Instinct line has taken time, and perhaps more time than AMD ever imagined. The long journey began with the “Graphics Core Next” architecture that debuted with the “Vega 10” Radeon and Radeon Instinct MI25 GPUs that were coming out in the summer of 2018 as Nvidia had captured a big chunk of the pre-exascale system deals in the HPC centers of the world with its “Volta” V100 accelerators. This is when machine learning on GPUs had surpassed human capabilities for image recognitive five years earlier and models were created to convert from speed to text or image to text as well as between spoken and written languages. This is also when AMD was not much of a threat to Nvidia when it came to GPU compute in the datacenter, and Nvidia was gearing up to do its own CPUs to be a threat to Intel and AMD on that front.

With the “Navi” Vega 20 GPU that came out ahead of the SC18 supercomputing conference in 2018, used in the Instinct MI50 and MI60 GPU accelerators, AMD demonstrated that it could put together a credible GPU, but we never really saw the top-end MI60 come to market and even though these devices offered pretty good price/performance, the Radeon Open eCosystem (ROCm) software stack was a toy compared to the Nvidia CUDA stack and libraries, which had a decade more development at that point.

We really count the Vega 10 and Vega 20 as one effort, kind of stretched across a couple of years and just really giving AMD a baseline from which to start a real GPU effort.

With the “Arcturus” GPU that was announced at SC20, we said that AMD was at a tipping point with the Instinct MI100 GPUs that used this very respectable GPU as well as the evolving ROCm stack, and we stand by that assessment. A year later, ahead of SC21, AMD launched the “Aldebaran” GPU, which is more or less two Arcturus units in a single package, and this is the GPU that was at the heart of the Instinct MI250X accelerator that was deployed in the “Frontier” supercomputer at Oak Ridge National Laboratories and that broke the exascale computing barrier. (And yes, it most certainly was a barrier.)

With the “Antares” Instinct MI300 series, this is the third time charm for AMD’s datacenter GPU business, and the company is gearing up to have a significant GPU business, which the company finally put some numbers on as it went over its third quarter financial results. The MI300A variant of the Antares accelerator is a hybrid device with CPU and GPU motors sharing a 128 GB chunk of HBM3 memory and is the core of the “El Capitan” supercomputer being installed right now at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. El Capitan is expected to deliver more than 2 exaflops of aggregate peak FP64 floating point oomph, which will make it the fastest machine on Earth – at least for a while. The Instinct MI300X accelerator is an all-GPU device with 192 GB of HBM3 memory and is going to drive sales into hyperscale datacenters and cloud builders, and it looks like the big bump there is coming in Q1 2024.

AMD is going to launch the MI300 series GPUs in San Jose on December 6, but it can’t contain its enthusiasm about the fact that it looks like it will have material – and sustainable – revenues from datacenter GPU sales.

“Based on the rapid progress we are making with our AI roadmap execution and purchase commitments from cloud customers, we now expect datacenter GPU revenue to be approximately $400 million in the fourth quarter and exceed $2 billion in 2024 as revenue ramps throughout the year,” Lisa Su, AMD’s chief executive officer, said on a conference call with Wall Street analysts going over the financial results for Q3 2023. “This growth would make MI300 the fastest product to ramp to $1 billion in sales in AMD history.”

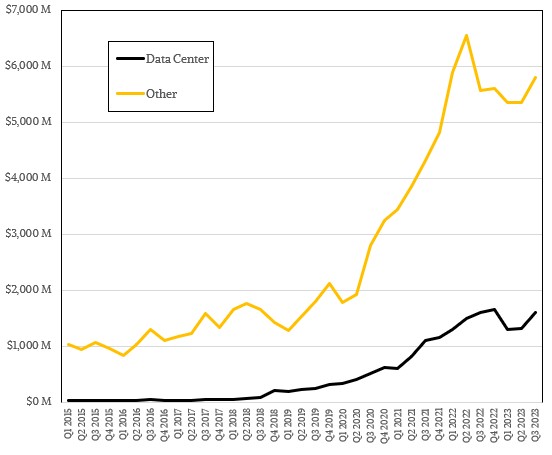

True, but the runway for that ramp was built starting back in 2015 or so – just like the Epyc CPU ramp. But, way back then, AMD was too small and too weak to go gangbusters on both CPUs and GPUs at the same time. In a very real way, the success of Epyc has funded the success of Instinct.

Being more specific, later in the call Su said that AMD expected the Instinct line would drive around $400 million in sales in Q4 2023, with that mostly being driven by the HPC market with some early ramping of AI workloads at hyperscalers and cloud builders who are voracious in their appetite for any kind of matrix math compute these days. We think that somewhere around $300 million of that $400 million is going to pay for the MI300A hybrid CPU-GPU compute engines in the El Capitan machine. In the first quarter of 2024, AMD expects another $400 million or so in Instinct sales, driven mostly by AI with a small piece being for HPC systems. (Sometimes it is hard to say where that line is.) And for the rest of 2024, Instinct sales will ramp and be mostly focused on AI workloads, culminating in around $2 billion in revenues for the full year.

If you do the math on that, it looks like AMD will be adding around $50 million in incremental datacenter GPU revenue sales in each quarter in 2024 to hit that $2 billion number. In Q3 2021, when AMD booked a big chunk of the MI250X GPU sales for the Frontier system, we estimate that it had $164 million in datacenter GPU sales, and it did another $148 million in Q4 2021 in our model. So that $400 million in the current quarter and in Q1 2024 represents not only a price hike for GPUs but also a significant increase in volumes.

Here is perhaps a better comparison. In the prior five quarters when the MI200 series has been fully ramped, we think AMD had on the order of $315 million in datacenter GPU sales, and that is just nothing compared to the $2.4 billion in revenues that AMD tells us – with pretty good confidence because we think all of the MI300 series it can make have already been allocated to OEMs, clouds, and hyperscalers – it can do in the next five quarters. That is a factor of 7.6X jump in revenues. And, by the way, we think that AMD is entirely gated by the CoWoS chip packaging it can get from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co – not Antares GPU chip yields, not HBM3 memory availability. If TSMC could make more MI300 units, then AMD could sell more MI300 units. Clearly, there is a big CoWoS ramp coming in 2024 for AMD, but Nvidia can outspend AMD on HBM3 memory and CoWoS given its vast wealth and dominant position.

Still, even though Nvidia has a much bigger datacenter GPU compute business, but no one will be able to claim that AMD is not innovating in its own right with chiplets and stacked memories and such and that it does not have some of the smartest minds on Earth now eager to make their software run on AMD GPUs so they are not wholly dependent on Nvidia GPUs. The market is entirely over that dependence, just like it was with Intel’s hegemony in the datacenter in the late 2010s.

Competition is not just coming for Nvidia, it has arrived. And it ain’t gonna abate. Period.

The only question now is how fast can the hyperscalers and cloud builders create and ramp their own custom ASICs for AI. Nvidia will react and innovate, as will AMD, but there is no question that Nvidia is at peak control and peak pricing in the datacenter. Which is why it might be thinking about taking on Intel and AMD in the market for client CPUs with its own Arm chips. If someone attacks you on one front, you defend and open up a fight on another front.

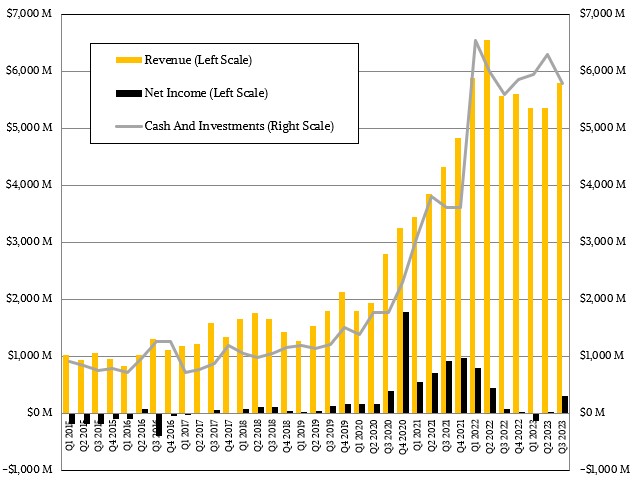

Because of the “Genoa” and “Bergamo” Epyc server CPU ramps and some renewed spending by clouds, hyperscalers, and some enterprises for top-end CPUs outside of AI systems and a recovery of sorts in PC spending, AMD’s third quarter was not as bad as the prior two quarters of 2023. AMD booked $5.8 billion in total revenues, up 4.2 percent, and net income rose by a factor of 4.5X to $299 million.

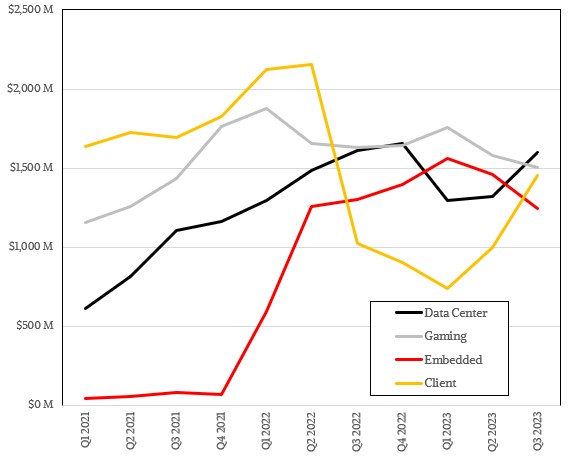

The Client group, which sells CPUs and GPUs for PCs, had $1.51 billion in sales, up 42.2 percent, and it shifted from a $26 million operating loss against $1.02 billion in sales in the year-ago period to a $140 million operating gain this time around, which helped. Gaming sales – mostly discrete GPUs aimed at gamers plus game consoles, as the name suggests – posted $1.51 billion in sales also, but down 7.7 percent, although operating income rose by 46.5 percent to $208 million. The Embedded division, which is largely the Xilinx business not related to the datacenter, had $1.24 billion in sales, off 4.6 percent, and an operating income of $612 million, off 3.6 percent.

You can see why AMD paid so much for Xilinx. This unit has almost as much operating income as the Data Center, Client, and Embedded divisions combined.

Let’s drill down into the Data Center division now. In the third quarter, revenues across CPUs, GPUs, DPUs, and a smattering of other things were just a hair under $1.6 billion and fell by seven-tenths of a point year on year but rose by 21 percent sequentially from Q2 2023. Operating income was down 29.4 percent to $306 million, pushed down primarily by investments in future AI products, according to AMD.

AMD said on the call that in terms of Epyc CPU sales, customers have reached the crossover point with Zen 4 products, which is Genoa, Genoa-X and Bergamo, and Siena by the codenames. (Those links are to our coverage of those Epyc CPU launches if you want to drill down.) Our model says that AMD had $1.48 billion in Epyc CPU sales in the quarter, which is flat as a pancake year-on-year and which is a hell of a lot better than the stomach punch that Intel suffered in the same quarter, where its Data Center & AI group had sales of $3.81 billion, down 9.4 percent and shipments off 35 percent and average selling prices up 38 percent. AMD did not provide any guidance on Epyc shipments or ASPs. But we will give it a shot on statistics we think are relevant.

We think that hyperscalers and cloud builders comprised around 88 percent of Epyc CPU sales in Q3, which is a little over $1.3 billion in revenues and up 10 percent year on year and up 45.3 percent sequentially. If that is correct, then enterprises, telcos, service providers, governments, and academia accounted for only 11 percent of Epyc sales, which is $178 million and down 40 percent year on year. We also think that datacenter GPU sales were around $50 million in Q3 2023, down 28.6 percent as customers await the MI300 series and driven mostly by customers taking the MI210 and MI250X GPUs they could get. Datacenter NIC and DPU devices drove another $15 million in sales during AMD’s third quarter, we think, and Versal FPGA devices for the datacenter drove maybe another $52 million in sales and have been sliding sequentially during 2023 thus far according to our model.

This is admittedly all a lot of guesswork. But these numbers fit what AMD said on the call, and didn’t violate the sensibilities of the people on Wall Street who also build models and who we talked to as we were building ours.

, pushed down primarily by investments in future AI products, accordomg

Huh?

Operating income was affected by current R&D in future AI products.

accordomg (n): portmanteaucronym of various origins. Example 1: according to … Oh My God! Nicole! The GPS RoombAI is mowing the neighbor’s angora rabbits! Example 2: accordeons are a type of … Oh My God! Nicole! An herbaceous stratocumulonimbus just landed in the backyard, with a banjo! etc … 8^P

OHHHHH. I had a brain short circuit. Kids home today, lots of “Dad, I need….” Ha. I kinda like “accordomg”

I realize that it takes a long time to get a supercomputer installed, tested, tuned, and qualified. Also, I can see that Aurora’s install was ongoing on 05/27/23 (TNP), and rather complete on 06/27/23 ( https://www.nextplatform.com/2023/06/27/argonne-aurora-a21-alls-well-that-ends-better/ ), while El Capitan’s install started in earnest near 07/10/23 ( https://www.nextplatform.com/2023/07/10/lining-up-the-el-capitan-supercomputer-against-the-ai-upstarts/ ) … and so, as rumours were that Aurora’s HPL benchmarking was still being finetuned up to about last week, I really have to wonder if El Capitan managed to beat the clock with the desired impressive results (I sure hope so!), for this most imminent round of the Battle Royale (SC23)!?

AMD seems awful mute about this … (a vow of silence by meditative HPC monks?). Anyone with insight out there?

I’m sure AMD is keeping their powder dry to make a big splash at SC23.

Can’t wait to hear that buccaneer’s cannon fire!

I’ll add that, in this, both Motley Fool and Tom’s Hardware get points off for publishing an inaccurate automated transcription of AMD’s 10/31/23 earnings call that so mis-stated the timeline of MI300A’s shipments to El Capitan! Humans (hopefully knowledgeable ones) still got to double-check those error-prone automated gizmos (or maybe just stick to reading the more accurate and trustworthy TNP).

MI200 is not just two MI100 in one package. In fact, there is a single die version in the MI200 series: the MI210. Just put the specs of MI100 and MI210 next to one another and you will see that they are different beasts. The MI200 series has much better FP64 performance. After all, it was in the first place developed as the GPU for Frontier which was designed to be a machine more for simulation than AI (and its procurement dates back to before AI was that much a hype as it is today). The matrix units are also heavily reworked from MI100 with support for FP64 matrix operations (useful in codes that use dense linear algebra) and better performance for bfloat16.

Agreed. But it is a 20 percent tweak in features on Arcturus to get to Aldebaran, not a complete from scratch redo.

“AMD will be adding around $50 million in incremental datacenter GPU revenue sales in each quarter in 2024 to hit that $2 billion number”

Should read $500 million per quarter.

No. $50 million incremental to the $400 million in Q1 2024. Still badly written by me, and my model says $400 Q1, $450 Q2, $550 Q3, $600 Q4.

I could have been more precise in my report, and I can understand completely the “kids at home” issues, though mine are now old enough to drive themselves places.

But overall, I love your work here, it’s really interesting and a good dive into what’s happening in the base layers of systems and hardware and how that will affect IT pros. And glimpses of where the world might be going. Personally I think the AI stuff is way over hyped, like Bitcoin and all that stuff.

P.s. Akismet seems to think this comment is a duplicate of my original one. Sigh….

A couple notes and suggestions. Note that the Gaming segment has Consoles (they aren’t in Embedded which is almost 100% Xilinx). Console sales have dipped, but gaming dGPUs are still selling and at better margins, hence the increase in profit margin% despite drop in revenue in the segment.

It would probably also be better to use free cash flow or non-GAAP profits in the first chart, which for AMD better highlights their true profitability. Using GAAP numbers is skewed by funny accounting gimmicks (see that big spike in Q4 2020, AMD claimed old tax losses. And the near zero profits recently is AMD writing off fake losses and intangibles when they bought Xilinx with shares, not cash).

Right. I keep thinking of the old Semi-Custom and Embedded division pre-Xilinx.

As for GAAP versus non-GAAP. I think they are equally disingenuous. You can’t call an underlying business more profitable if the overlying business is a huge cost, or has to take a writeoff, or whatever shenanigans (or benefits) happen from time to time. The way I see it, only real net income counts. Because that is the money you can spend,

Timothy, gaming includes consoles. Embedded is Xilinx + embedded-style Epycs.

“The long journey began with the “Graphics Core Next” architecture that debuted with the “Vega 10” Radeon and Radeon Instinct MI25 GPUs that were coming out in the summer of 2018…”

This is wrong. Vega was the last GCN architecture, not the first. The first was Tahiti, which released at the end of 2011. The top-end consumer GPU using it was the 7970. The server GPU based on Tahiti, released in mid-2012, was the FirePro S9000.

After the Vega-based Instinct cards, AMD evolved GCN into CDNA, which is the architecture used in all the Instinct cards from the MI100 onwards.

I am not talking about the FirePro S9000, which was — how shall I say it? — not very good and was not a real Instinct card. The first CUDA-enabled GPUs were also not really datacenter-class products, either. I see your point, but I suspect you can see mine.