We have been tracking the financial results for the big players in the datacenter that are public companies for three and a half decades, but starting last year we started dicing and slicing the numbers for the largest IT suppliers for stuff that goes into datacenters so we can give you a better sense what is and what is not happening out there.

We call the big IT players the Thundering Thirteen, and in the final quarter of 2023, which is the latest data we have because we are only going to be starting the Q1 2024 earnings season on Friday this week, they broke through $100 billion in cumulative sales. And while it may feel like it, AI systems did not drive all of that growth throughout 2023 to reach that quarterly level – but we have a hunch that it did drive a lot of the profits in the datacenter sector.

The Thundering Thirteen are familiar to anyone who follows the datacenter. The biggest compute engine suppliers – Intel, AMD, and Nvidia – are part of this group. It is hard to peel out the datacenter businesses of chip makers Marvell and Broadcom, but we may do that at some point and then add them in.

IBM, Hewlett Packard Enterprise, Dell, Lenovo, and Supermicro represent the original equipment manufacturers who sell systems to enterprises and sometimes to hyperscalers and cloud builders. The revenues and operating income shown in our data is for sales of servers, operating systems, systems software, tech support, and maintenance, but does not include database or application software.

In networking, Cisco Systems and Arista Networks do the representing, and with Arista we are able to make pretty good estimates about how much of its sales are driven into datacenters as opposed to the campus and the edge. We have some hints about how much of Cisco’s switching business is driven by datacenter rather than campus and edge use cases, and eventually we will try to peel that out, but this is difficult because Cisco has lumped servers, storage, switching, and routing into one giant group.

And finally, we have the three big clouds: Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud. And in the case of Microsoft, we extract out the systems programs in the Windows Server stack – the operating system and related systems programs but not databases or application development tools – to figure out the total Microsoft systems business, including software for premises gear and cloud serving, storage, and networking capacity.

By the way: HPE, Dell, and Nvidia have quarters that do not align to the calendar quarters, so we allocated their revenues to the closest calendar quarter.

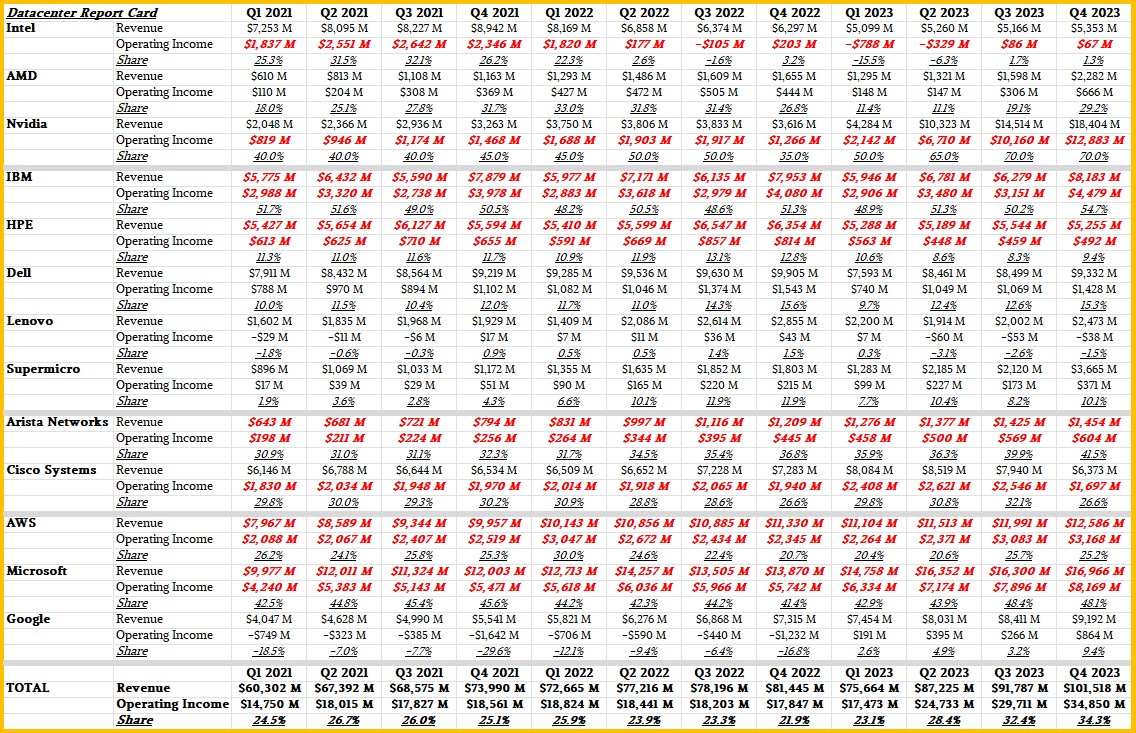

In many cases, vendors provide revenue and operating profit figures for their datacenter divisions. Sometimes they do not provide revenues for datacenter sales and we have to estimate them (as we have long done with IBM and Intel, for instance, call it their “real” systems businesses, for instance). Sometimes vendors do not provide operating income for their datacenter divisions and we have to take our best guess at allocating operating profit or loss from the overall company to the datacenter products. Anything in the table below marked in bold red italics is estimated.

Here is the chart with all of the raw numbers in it for datacenter sales and operating income from the Thundering Thirteen:

That is hard to take in, and we do not claim this model is perfect, but we think it is a pretty good heatmap of what is happening in the glass houses of the world. (They’re more like server warehouses these days. People don’t show off their gear, they try to hide it.)

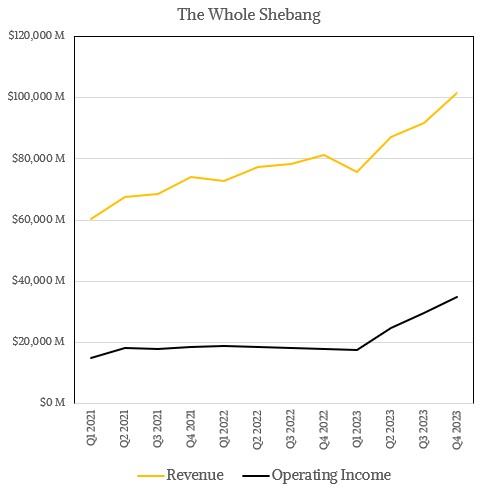

We know that just adding up the revenues and profits of these thirteen companies is a little bit mixing apples, oranges, plums, and pears, but so are the various stock indices that we gauge the health of the stock market upon. So let’s start with the Q4 2023 datacenter infrastructure report card by adding up the past three years of revenues and operating profits from the Thundering Thirteen.

As you will see, this is a representative chunk of IT spending in the world these days. There is some overlap in the numbers – obviously chips and systems software are turned around and sold by the OEMs and clouds as complete systems. But the aggregated numbers represent a kind of holistic view of revenues and profits across the datacenter.

As you can see, revenue growth slowed in 2022 as the year went on and operating income growth slammed on the brakes hard in Q2 2022 and actually went negative – meaning profits shrank – in the end of 2022 and at the beginning of 2023. Not hugely so, but down in a market where revenues were growing in the double digits year on year.

And then, the generative AI explosion hit and Nvidia went off like a hydrogen bomb. Nothing quite like the fourth wave of commercial computing with too much demand chasing too much supply to boost revenues and profits.

In Q4 2023, revenues across the Thundering Thirteen were up 24.6 percent to $101.52 billion, but operating income rose nearly four times faster at 95.3 percent to $34.85 billion, which represents an astounding 34.3 percent of revenues. At the beginning of this three year span, in Q1 2021, Nvidia comprised 3.4 percent of the total revenues among the Thundering Thirteen and a very respectable 5.6 percent of operating income in this datacenter space.

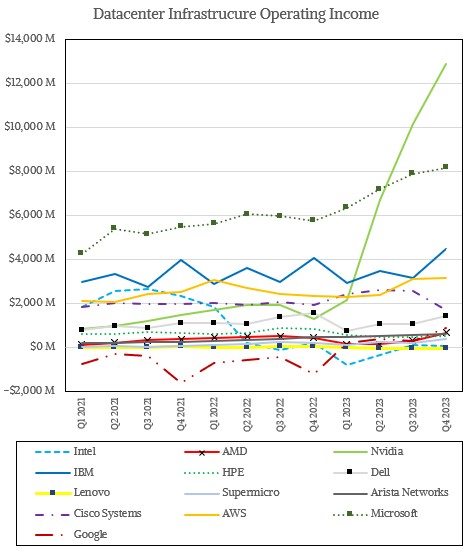

In the December quarter, Nvidia’s share of revenues has risen to 18.1 percent – a factor of 5.3X growth – and its share of operating income has risen to 37 percent – a factor of 6.7X growth. At the beginning of the period, Nvidia was quite a bit more profitable than its datacenter peers at the company level – it is hard to beat the IBM mainframe when it comes to margins, even in 2024, six decades after the launch of the System/360 mainframe – but now you can see that it is ridiculously more profitable, approaching the combination of IBM mainframe hardware and software margins together and with a 9X more revenue growth between Q1 2021 and Q4 2023, Nvidia has the most profitable datacenter business in the absolute sense as well as in a relative sense comparing profit to revenue ratios. (We have estimated Nvidia operating margins based on the limited figures it released for a few quarters before it thought better of advertising these statistics to its rivals and customers.)

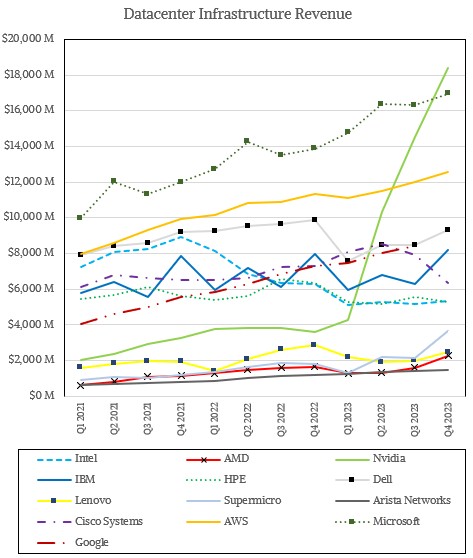

Here is what it looks like if you break all of the vendors down separately and show their datacenter revenues on the same chart:

With that, you see that Microsoft was the biggest player in the datacenter, but now Nvidia is. And there is no indication that this will change any time soon. Eventually, in perhaps 18 to 24 months, Nvidia’s business will reach an equilibrium. And guess what? Microsoft will pass Nvidia again in terms of absolute revenues.

Now, when it comes to profits, we think Nvidia will be able to stay ahead of Microsoft for a little bit longer.

But, in the fullness of time, the Microsoft platform, consisting of Windows Server plus Azure, will inevitably catch up on profits, too – particularly as Microsoft develops its own CPUs, GPUs, and DPUs and increasingly cuts Intel, AMD, and Nvidia out of the loop.

Now, let’s talk about the compute engine makers for a second. Nvidia crossed Intel on the way down during its skyrocket in the datacenter business in Q1 2023. Both Intel and AMD have been hurt by the server recession that was caused in part by the need to conserve funds that might have otherwise been spent on generic infrastructure so money would be available for expensive AI systems.

Intel is in the middle of recasting its revenues and profits, and this is the old method when the various Intel groups were paying more than market rates for chip fabbing and packaging and hence were less profitable than they are now shown to be.

Because this is our reckoning of Intel’s datacenter revenues, not just its Data Center and AI group sales, nothing Intel does with its financial reporting will shift that dashed blue line up the Y axis to be more money. But the changes it is making by separating out Intel Foundry will absolutely shift the dashed blue operating profit line up the Y axis once this process is completed. (We do not have quarterly figures for this yet, just annual ones, which we described here in a separate story.) Suffice it to say, neither Intel nor AMD are particular profitable in the datacenter – at least not compared to Nvidia:

Amazing, isn’t it? And like all kinds of lines like these, we will point out the obvious truth: There is no way in hell this is going to last. We said it about IBM three and a half decades ago, we said it about Intel a decade ago, and we will say it about Nvidia now. We also said that you couldn’t count IBM or AMD out when they were down in the datacenter business, and only a fool would count out Intel in either the foundry or chip design/sales businesses. All three have survived near death experiences.

Now, let’s give a little love to the original design manufacturers, who collectively create hundreds of system designs made from compute engines, storage, networking and other components, and sell and support them for millions of companies worldwide.

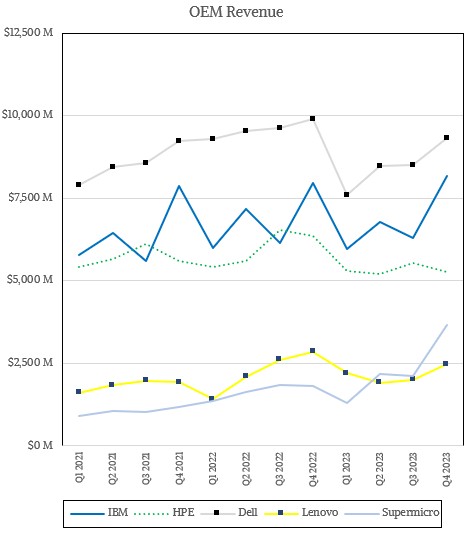

Here is the revenue for the five major system OEMs over the past three years:

Dell might be the biggest system OEM in the world with its PowerEdge server and Dell/EMC storage business, but IBM is not that far behind with its combined Power Systems servers and System z mainframes – largely because it controls the software stack on these and also controls the Red Hat Linux operating system and middleware that can – and often does – run on the OEM machines made by others.

Much is being made about the explosive growth that Supermicro has seen thanks to some big AI system deals, but it will take the company quite a while to catch up to HPE, which is the third largest OEM in the world. Supermicro has surpassed Lenovo, which has to walk a fine line given that it is a Sino-American company and driven in a big way by the former PC and X86 server businesses that it acquired from Big Blue.

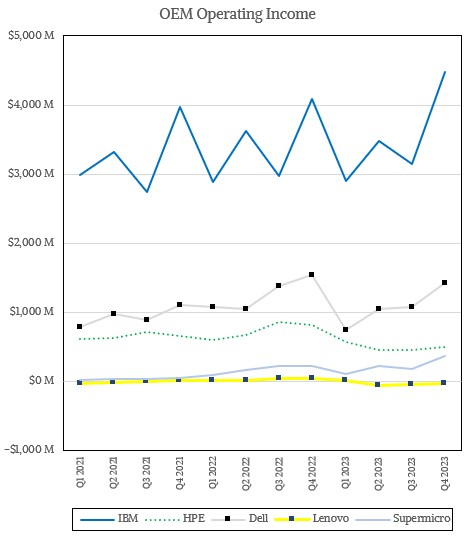

From software, comes profits. And this chart below showing the operating income from these five OEMs certainly shows that:

Lenovo has a hard time making money on its core systems business, and Supermicro has only been a little more profitable thanks to the GenAI boom. HPE’s system profits have been slipping as Supermicro’s have been rising – these are necessarily connected in a causal sense directly, but there certainly are indirect pressures that HPE has come under from intense competition from Lenovo and Supermicro. Dell generally makes more money from its datacenter systems business than these three, but is generally only about as third as profitable as the slightly smaller IBM systems business.

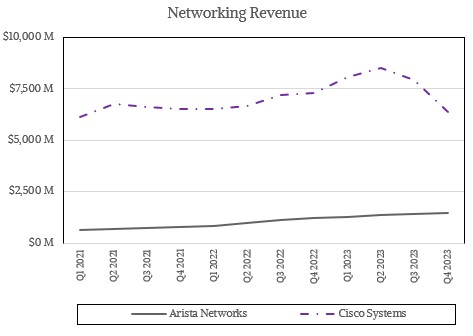

As for the networking segment, it would be harder to find a straighter set of lines than that of revenues and operating profits of Arista Networks between 2021 and 2023 inclusive. Here is the revenue for these two:

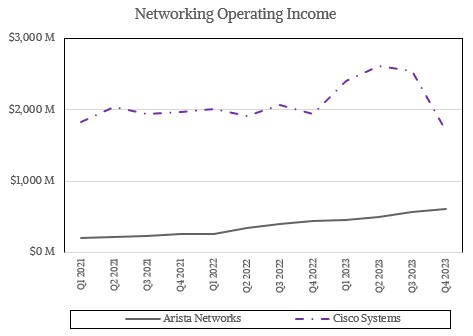

Here is how Cisco Systems and Arista Networks have done in terms of operating profit in the past three years:

As you can see from the charts above, Cisco was plugging along in 2021 and 2022, had a nice bump in early 2023, and ran out of gas in the second half of 2023. Cisco has over 90,000 customers using its UCS server platform and millions of customers using its switches, and we frankly do not know what happened there. You can also see that Cisco’s revenues and profits tend to grow in lockstep and Arista’s profits are generally growing a bit faster than its revenues.

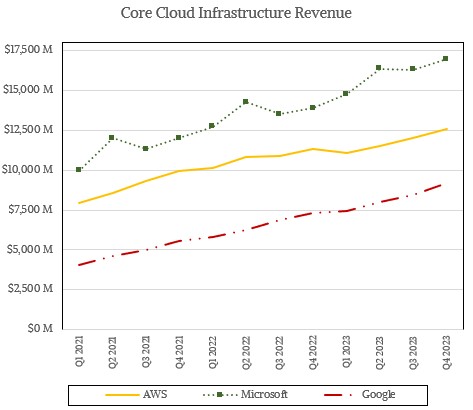

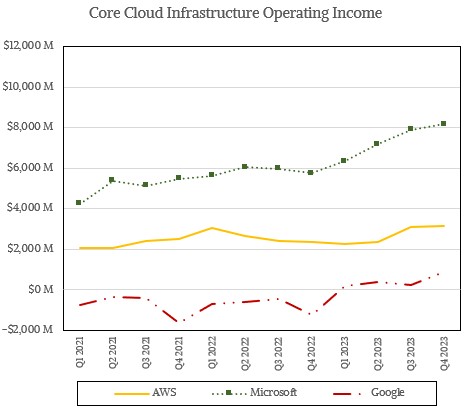

That brings us to cloud infrastructure, and there is no question that AWS, Microsoft, and Google are the bellwethers for the sale of infrastructure as a service capacity in the world. Here is how their revenues stacked up against each other in the Q4 2023 datacenter report card:

Microsoft’s operating profits across the entirety of its systems platform is growing slower than its revenues, but for AWS, which does not have an on premises legacy server platform business with tens of millions of customers as Microsoft does with Windows Server, its revenues are growing more or less in lockstep with Azure plus Windows Server but its profits have been staying just north of $2 billion per quarter.

Google’s cloud revenues have been growing more or less at the same rate, and thanks to accounting changes that keep servers and storage in the field longer, it has become moderately profitable in the cloud. Perhaps with the GenAI boom and its own TPUs, Google can finally make its cloud consistently and significantly profitable.

Wow! The impact of Nvidia being (essentially) first to market with an (rather) integrated hardware+software solution for AI/ML is really well illustrated in this analysis (excellent!). Their focus on making low-precision compute very fast (in HW and SW) looks to have been a winning strategy in this space so far (relative to making FP64 fast), especially as datacenters became more curious about AI/ML capabilities and applications. The next few reports should tell us whether AMD is lagging by 2-3 quarters, or more, in this opportunity (IMHO).

It’s also fun to see the broad variety of HW and SW currently competing in this emerging AI/ML arena (eg. as reported by TNP). It is somewhat reminiscent of the CPU and OS diversity that existed before industry “standardized” mostly on x86 and Windows/Linux (also some POWER and Arm, and BSD, but not superscalar, superpipelined, Fairchild Intergraph Clipper …). It’ll be interesting to see which way AI/ML goes, either towards standardization, or sustained HuggingFace-like diversity, or one specialized arch and software for each type of AI app? Economics of scale would suggest standardization, and a majorly entertaining rhumbamageddon of doom between the major players!

Nvidia has created the new System/360. There will be alternatives. Economics requires it. But provided we don’t have an extinction-level event, we think Nvidia will have a large and profitable share of AI compute and software for a long time. IBM’s System/360 got six decades and is still going. Nvidia will be strong as long as Jensen Huang is there. The minute he leaves, someone else will come in, just like the minute a Watson stopped running IBM then Big Blue started running up on the rocks in the late 1980s. It was just so big and profitable that it couldn’t feel it until maybe 1991.