The rumors were right, and AMD president and chief executive officer Lisa Su is indeed printing out a tower of stock to acquire FPGA maker Xilinx for what amounts to about $35 billion and, as it turns out, she is relinquishing her position as president to Victor Peng, chief executive at Xilinx, to close the deal.

Now, we have three big camps in the war over datacenter and edge compute. It is fall, the day is partly cloudy, and the economic weather is uncertain. But the troops are well fed and eager, their weapons glisten in the sun and the horses stamp their feet impatiently. Banners wave in the chilly wind that warns that winter will not wait. And so the war cannot, either. There will never be a better time to fight, or a better way to settle the architectural disputes.

On one hillside, we have Nvidia with its Mellanox and Cumulus networking plus its hegemony in datacenter GPU compute for HPC and AI and the potential to add Arm server chips and the Arm Holdings licensing method and 500-plus licensees to augment the Nvidia army.

Down in the lush valley is Intel, which has lots of provisions and plenty of money to fund the war, but it has nothing to gain from a fight except the loss of future fruitfulness and ease. Intel has added to its compute engine and networking arsenal and has given up on storage media to brace itself for the coming attack, and its engineers have struggled to build its engines of war and fortify its moat.

And on the other hillside is the combination of AMD and Xilinx. AMD, unlike Nvidia, believes in FPGAs as well as CPUs and GPUs. Much as Intel did five years ago as it spent $16.7 billion to acquire Xilinx rival Altera and scrapped its “Knights” massively parallel processor dreams to create the Xe line of discrete GPU accelerators.

Provided the antitrust regulators of the world allow for the AMD acquisition of Xilinx and the Nvidia acquisition of Arm Holdings to go through, this is going to be one hell of a battle over the next few years, and it will spill out from the valley or the datacenter out into the woods of the edge. And the one thing we know for sure is a whole lot of Intel CPU profits and quite possibly Nvidia GPU profits are going to disappear, never to be seen again, because that is what happens when there is a bloody price war at a time when all of the technologies are more or less equal among the rivals. In fact, that is precisely when a bloody price war always breaks out, and all of these acquisitions are just a preparation for this day, which was always coming.

In the meantime, before the fighting breaks out in earnest, we can talk about the skirmishes that AMD is engaged in down in that valley as it turns in its third quarter results and get into some of the details and commentary from Su and Peng about the Xilinx deal, which we pondered in our typical fashion weeks ago when the rumors of this deal first surfaced.

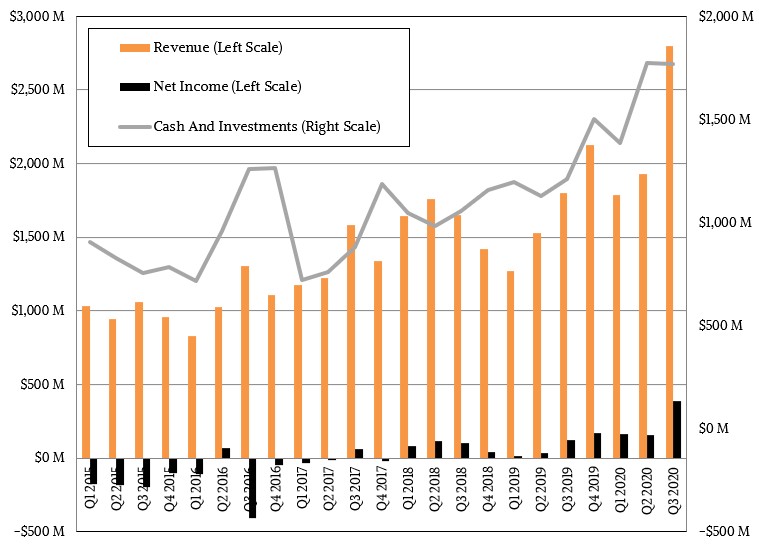

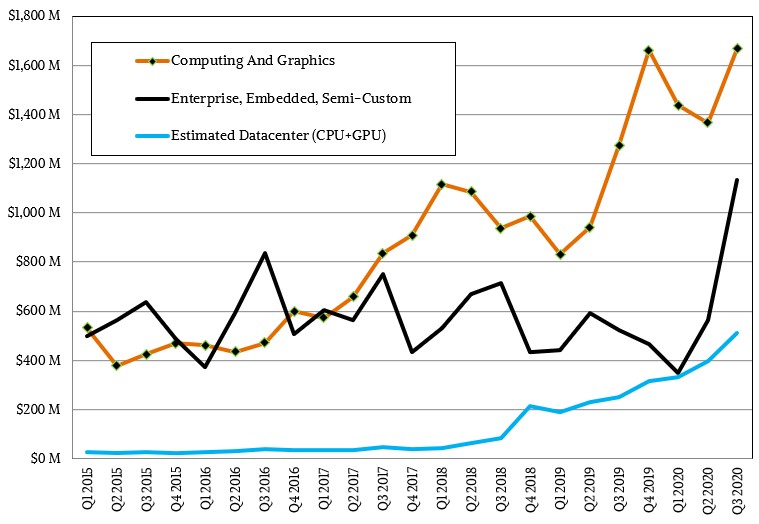

In the quarter ended in September, AMD’s overall revenues were up 55.5 percent to $2.8 billion, and net income more than tripled to $390 million, representing 13.9 percent of revenues and also representing something akin to what we think the overall profit level of compute engines will be in the coming years. (Think maybe 20 percent or 25 percent operating income, which gets busted down a bit to net income after taxes and other stuff are taken out, instead of the 45 percent to 50 percent operating income that Intel’s Data Center Group has enjoyed, with some wiggles here and there, since the end of the Great Recession. For instance, as we have already reported, in the third quarter when AMD was coming on strong, Data Center Group’s revenues were off 7.5 percent to $5.91 billion and operating income fell by 38.9 percent to $1.9 billion. Even if AMD only wins a certain amount of deals, it nonetheless causes Intel to cut price on the deals it does win, so there is a multiplier effect. And that bites directly into the middle line much harder than you might think. This is what a price war does.

AMD’s Computing and Graphics group, which includes client CPUs and client and server GPUs (both Instinct and Radeon Pro variants), posted sales of $1.67 billion, up 30.6 percent as the companies “Zen 3” Ryzen processors continue to take share away from Intel. This group delivered $384 million in operating income, up 114.5 percent (meaning up by 2.15X if you think that way, as I do when the percents get above 100 percent). The Enterprise, Embedded, and Semi-Custom group, which includes Epyc CPUs as well as embedded processors sold for microcontrollers and edge devices as well as custom game console chips, had an aggregate of $1.13 billion in sales, up 116 percent (or again, by 2.16X) and operating income hit $141 million, up 131.1 percent (or 2.31X).

Using the guidance that AMD gave during its call with Wall Street going over the Q3 2020 financials and the Xilinx deal, and making a few calls to Wall Streeters see if our model made sense, we reckon that 18.2 percent of AMD’s overall revenues came from its datacenter products, by which AMD means specifically Epyc CPUs and a tiny bit of embedded stuff sold into datacenters plus Instinct and Radeon Pro GPU accelerators. That’s up 102.3 percent year on year and up 28.7 percent sequentially from Q2 2020. If we break this down further, our model shows $445 million in Epyc CPU sales, up 112.4 percent year on year and up 33.1 percent sequentially, and $65 million in Instinct GPU sales, up 52.7 percent year on year and 4.8 percent sequentially.

What this shows us is that Intel did not have so much of a “digestion” problem among the hyperscalers and cloud builders, as it has claimed, but rather that hyperscalers and cloud builders have an indigestion problem with Intel compute engines.

And, thanks to the many delays with the 10 nanometer “Ice Lake” Xeon SP processors, which will ship for revenue this year but will not be launched until later this year, and the 7 nanometer slip for future Intel CPUs and GPUs and FPGAs, and AMD delivering third generation “Milan” Epyc 7003 processors before the end of the year – our guess is early customers have them now, and in volume, well ahead of launch, which is coming any day now – we think AMD is going to have an even better fourth quarter in the datacenter.

We already know Intel will have a not so good one, as it said last week to expect Data Center Group sales to drop by 25 percent in Q4. To give you a number, that is a decrease of $1.8 billion. And that probably means sales of Milan Epycs are doing quite well even as the hyperscalers and cloud builders digest. We won’t know for sure until Intel and AMD report their Q4 numbers in January 2020, but if even half of this decline is real and the other half is competition, and let’s say the revenue compression is $1 for AMD for every lost $3 in Xeons (and thus giving a much deeper hit on operating margins), then AMD could add maybe $300 million in incremental datacenter CPU sales. If that happens – and yes, there are a lot of ifs in this thought experiment – AMD would more than triple its Epyc CPU sales year on year.

Call it the first big skirmish in the Price Wars.

Our best guess is that game consoles represented $649 million in sales in the third quarter, up by a factor of 2.2X year-on-year, and there was another $40 million in embedded device sales, up by 2X. If these sales go down a bit in Q4, which is reasonable in that game consoles are being built now for the peak holiday season, and AMD can grow datacenter sales and there is not as big of a decline in spending as Intel is suggesting among hyperscalers and cloud builders, then we think that the bulk of the growth that AMD will see in Q4 to reach its estimated $3 billion in sales will come from the datacenter. But again, that’s a lot of ifs. We shall see.

Bringing The FPGA Banner Aside The CPU And GPU Banners

Now, let’s talk about the Xilinx deal.

As we have said many times before at The Next Platform, we believe that there is a place in the datacenter and at the edge for FPGAs. Maybe not enough to justify the cost of what Intel paid for Altera, or even what AMD is paying for Xilinx, but in both cases, that was the cost of buying not just a different compute engine, but a team of experts in an adjacent and important market – and both Intel and AMD are using funny money to pay for it. Intel was using its excess profits from its hegemony in the datacenter for close to a decade and a half and AMD is using the market capitalization of its stock, which is flying high as it starts to gain traction against Intel in the datacenter and in the client computer. You have to spend this capital somehow, and this is a choice companies often make at great cost. Sometimes it works out.

According to Su, by acquiring Xilinx, AMD has increased its total addressable market to $110 billion, which is up from $79 billion that AMD believes it can chase with its current CPU and GPU products. That is a $12 billion TAM in gaming (meaning console chips as well as GPUs for gamers), a $32 billion TAM in PCs CPUs (which sometimes have embedded GPUs), and $35 billion in the datacenter. As we calculated in our original coverage on the rumored deal – which had it pegged at $30 billion when it is actually going to cost $35 billion – AMD is going to basically double its datacenter business (and to be super-precise, from the level we saw in the trailing twelve months working back from the end of Q2 2020 as we wrote our story three weeks ago) by acquiring Xilinx. In the long run, as Epyc CPUs take share and Instinct GPUs take share in HPC and AI systems – look at all of those pre-exascale and exascale systems on the horizon, and look at all of those all-AMD systems we keep writing about that are mimicking them on a smaller scale – it would not be surprising if Xilinx represented something like 25 percent of AMD’s overall datacenter sales when it all settles in after the battles with Intel and Nvidia are fought.

And to be fair, AMD has already fought major battles, with the Cray battalion of the Hewlett Packard Enterprise army by its side, to win those pre-exascale and exascale deals, and it has driven Nvidia and Intel from those fields.

Many people question why AMD is doing this now. And the answer is simple: Because AMD can do it now, and in a way that it could not do without the resurgence in Ryzen and Epyc. A decade ago, and maybe even five years ago, Xilinx looked like a better bet in the datacenter than AMD. And so, maybe Xilinx could have bought AMD, but it could not have happened the other way around. Now, AMD’s market capitalization is roughly three times as large as Xilinx’s today – $96.5 billion versus $28.1 billion, respectively as we go to press. Excepting a brief time in late 2005 and throughout 2006 when the Opteron CPUs were flying high, Xilinx had a higher market capitalization than AMD. In fact, in 2008 and again in 2012 through 2015, Xilinx was four to five times as large, in terms of aggregate stock value, than AMD. The Intel-Altera deal made Xilinx stock go crazy – not at first, mind you – and the two companies tracked in size, more or less, between then and the middle of 2019. That was when Xilinx started to slip – we think mostly because of Intel’s lack of growth in FPGAs and the FPGA craze abating a bit, not because of the execution that Xilinx had done on its roadmap, which has been steady. As has been its market share gains in the FPGA space. It wasn’t until this year that AMD could even think of doing such a deal based on swapping stocks. And there is no way, with only $1.71 billion in the bank, that AMD could come up with $35 billion in cash.

But just because AMD can do it now doesn’t mean it should do it now. So why should AMD acquire Xilinx now? This was the main question on the call with Wall Street, and Su laid it out as someone pointed out that the Intel acquisition of Altera has not exactly panned out as planned. We will let Su explain:

“We have been thinking about this for some time, and I think it’s actually a very different situation in that Xilinx is the market leader,” said Su. “If you look at how their business has grown over the last few years, their market share has continued to grow. I think both companies are executing really well. So you ask why now? We feel very good about our base businesses. I think the people look at our businesses and say they’re complementary and they are very complementary from a product and market standpoint. But we have sort of important intersections around the datacenter focus and then also around the technology strategy. We are both leading edge technology users. We both have partnered with TSMC. We both have really leaned into this modular design environment, and Xilinx is a leader in some of that with the 2.5D and 3D integration. We’re both invested in software and open source. So there are a lot of synergies that are under the covers and we see them very strongly. And I think you will see as the roadmaps execute. And then I think the last point I’ll mention is, I think our cultures are very, very aligned and we’re both Victor and I are both engineers at heart. We love the technology we have a common vision, I’m really, really happy that he is joining me on this journey. I think, we have a bold vision of what we think we can do for the industry and for our joint companies.”

A merger of equals, or near equals, is fine by us, and is in fact what we prefer for all parties when it makes sense as it does in this case. Just because acquisitions don’t often work out doesn’t mean mergers can’t work better. And we think, given the personalities of Su and Peng and the temperament of their respective teams, and the near lack of overlap between the two companies, this merger will go off better than most.

AMD expects for the deal to close by the end of 2021, subject to the customary regulatory approvals, and until that time both companies will continue to operate as they normally do and partner as they normally do. We think it is highly unlikely that anyone will offer a counter deal for Xilinx. Nvidia doesn’t believe in FPGAs, IBM doesn’t have any money, Intel has been there and done that, Broadcom is always an outside shot, and Marvell is too small at a market capitalization of only $27.8 billion but could be a merger of equals if it decided to do that.

If for some reason this deal does not go through – and we give it much higher odds than Nvidia buying Arm because it is less globally politically contentious for a number of reasons – AMD can always backstep and buy Achronix for FPGAs and Innovium for networking and build out its chippery. But the Xilinx deal is about buying a real, dependable, and flowing revenue stream and a large team of industry and technical experts and a very large portfolio of intellectual property. And hence, the very high price tag. But this is just Wall Street money, not the real stuff. So AMD might as well spend it while it has it.

We will finish up with a few initial thoughts. First, AMD expects for there to be $300 million in cost cutting synergies in the 18 months after the deal closes. The obvious ones here are the typical back office stuff, but the not so obvious ones are in the design of specialized interconnects and other hard-coded IP blocks that both AMD and Xilinx would need independently. Moreover, it is going to get more difficult, and therefore more risky, to design faster and faster SerDes circuits, and this mitigates that risk by bringing the smartest people from the two companies’ teams together. Another funny thing is that AMD will now be able to get FPGAs at cost to do its simulations of future processors, which is a small thing admittedly. But the important thing, we think, is the expertise in chiplets and interconnects that both AMD and Xilinx have, and how they learn to package up compute and networking elements into systems. This is the real value that AMD is getting – and that Xilinx is also getting.

We would not even be surprised to see AMD buy Innovium next to get its hand on some Ethernet switch ASICs to complement the Xilinx SmartNICs. This would be small potatoes compared to the cost of buying – really merging with – Xilinx, and it would make sense if you believe networking is an important part of the datacenter stack and the two main rival armies have their own. Which Nvidia and Intel do.

Thanks for an excellent and insightful piece.

Just an FYI on the DC GPU revenue. It’s actually in the C&G group, under Graphics, not in EES&C as you’ve indicated. So overall, AMD’s DC revenue is a bit higher closer to 20% of total revenue.

It’s not true that Lisa Su is relinquishing her position – in their own press release it is explained Su will remain CEO over the combined company and Victor Peng will be president of the Xilinx division (https://www.amd.com/en/press-releases/2020-10-27-amd-to-acquire-xilinx-creating-the-industry-s-high-performance-computing)

No. What I said is that she is relinquishing her position as president. She still remains CEO. She had both before this deal closes.

AMD for q3

1K AWP for quarter $579.63 / 3 stakeholder split = $193.23 < 35% bundle deal sales incentive sacrifice = $125.60 gross per unit.

$2,804,000,000 quarterly revenue / $125.60 = 23,234,085 units produced up 51% from q2 and a record quarter.

All toll AMD has produced 51,823,417 units for the year and needs 19 million to make their own q4 total revenue objective and 29 million to make 2020 leadership plan objective.

AMD ends for the year between 70 and 80 million units sold through.

Q3 by product category;

Epyc Rome = 2,171,047 units at 9.72% of total volume; half of which are suspect Intel XSL/XCL parity sales incentive; buy one get one, which won't show in the financial but suggests on channel data and economics assessment. Rome channel volume q3 is up 160% over q2. AMD records between 849,317 and 1,085,523 revenue units up 26% to 50% over q2.

Note best Thread ripper quarter is 2,720,104 units produced q3 2019. Rome shows record volume and AMD hides cost of sales on Intel competitive sales parity.

Thread ripper 30X0_ = 232,753 at 1.04% of volume.

Ryzen 3xxx_ = 11,835,315 is 53.02% of full line volume. Ryzen 5xxx_ = 3,594,633 at 16.10%. Record desktop quarter volume. In part 3xxx suspect thrown in to offset OEM 5xxx platform development expense. AMD quarterly revenue sacrifice has consistently been running around 35%; bundle deal sales close incentive. This is the new Intel Inside along with the old Intel technique of buy two for one and all derivatives thereof. I don't believe 2 for 1 will survive into Xeon Ice lake on DCG operating at cost through q3; just getting rid of remaining Skylake inventory primarily.

Ryzen 4xxx APUs = 965,077 at 4.32%. Renoir appears stalled proliferation misrepresented by AMD. The best tech does not always win. Intel remains the supply power house and OEMS bought off on 10 nm Tiger Lake on Intel ability to supply in volume, including the potential of into future product contract ties.

Console = suspect (ramp) 1,065,268 at 4.77% of volume that may not be volume at all but a license fee about $50 each.

dGPU, 60K DC on prior estimates I've also calculated 43Kish and remainder Big Navi = 2,459,805 at 11.02% of full line volume up 34% over q2.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing