One of the key strategic moves that AMD made when it architected its comeback in the datacenter was to beef up the compute, I/O, and memory on a single server socket while at the same time making that socket out of chiplets that were significantly cheaper to manufacture and integrate than a monolithic chip was to put into the same socket.

This strategy may be starting to get some traction in the market, if the recent data and comments from the analysts at IDC are any indication. And we think that more than a few hyperscalers, cloud builders, and HPC centers have been listening to what AMD has been preaching as the new server gospel since the “Naples” first generation Epyc 7001 chips debuted. Dell did a lot of the math on single-socket servers, too, and we explained that Intel would have to respond to this single-socket threat in a way that is more meaningful than doing what it already does, such as rolling out the “Rocket Lake-E” Xeon E-2300 chips for single-socket servers earlier this week. Intel has had a wimpy single-socket and a wimpy strategy, and AMD has a brawny one of both.

AWS is using Graviton and Gravition2 single-socket machines in its vast EC2 server fleet. Google, as we have previously reported, is rolling out its Tau instances on the Google Cloud based on a single-socket “Milan” Epyc 7003 server node to drive down costs while driving up performance. Significantly, Google says that a single-socket 60-core Epyc server can offer 56 percent higher performance and 42 percent better bang for the buck than Amazon Web Services can do with its single-socket Graviton2 nodes.

We similarly know for a fact that a lot of the future AMD-based CPU-GPU hybrid supercomputers going into the national labs — the 1.5 exaflops “Frontier” supercomputer going into Oak Ridge National Laboratories later this year and the 2.1 exaflops “El Capitan” supercomputer going into Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in 2022 are good examples — are based on a server node with one CPU and four GPUs. There are many more examples, and we think there will be more.

The net effect of some of the market moving to single-socket machines in the datacenter — single-socket machines have been commonplace besides desks and inside of closets at small and medium businesses for decades — will be to drive server node counts up and revenues per node down because there are extraneous components and costs in the two-socket system. In the past, customers often had to have two processors to get the I/O capacity or memory capacity or memory bandwidth for a specific amount of compute, but with the way AMD and the Arm collective are designing servers, a single-socket ship has lots of capacity and I/O to balance against 64 cores or 80 cores and soon 128 cores.

Such transitions take time, and by no means indicate that the days of NUMA servers are numbered.

“Broadly speaking, server market performance was muted in the second quarter as the market shifted slightly towards single-socket server configurations,” explained Paul Maguranis, senior research analyst of Infrastructure Platforms and Technologies at IDC, in a statement accompanying the server market analysis covering the second quarter of 2021. “While servers purchased directly from ODMs declined year over year, some past backlog recovery within the hyperscale datacenter community contributed to a large jump in this segment when compared to the first quarter of this year.”

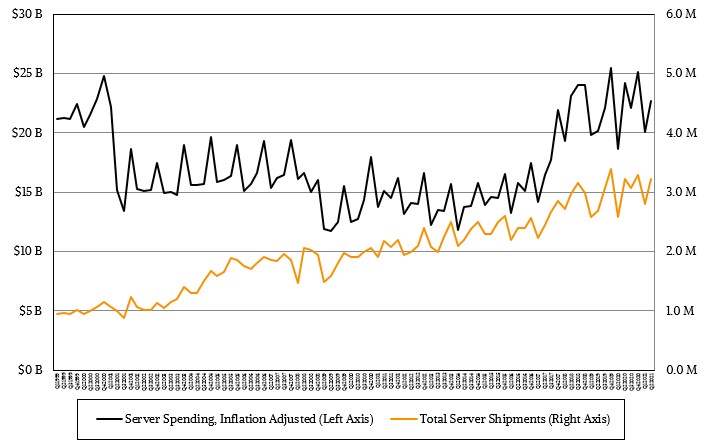

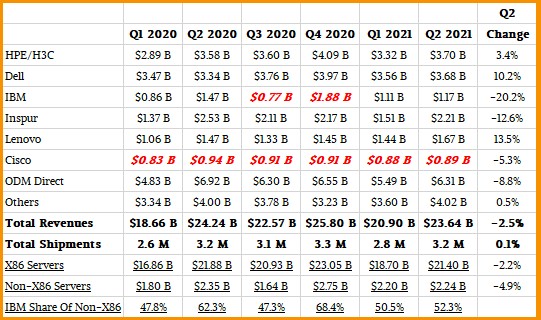

In the quarter ended in June, server shipments were up a mere one-tenth of a percent to just over 3.2 million units, while revenues declined by 2.5 percent to $23.64 billion.

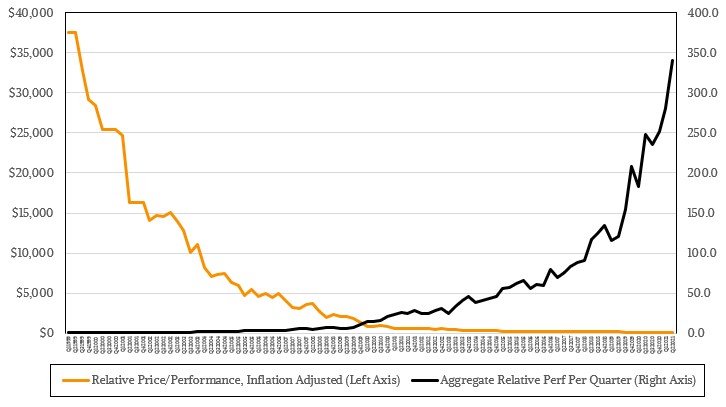

In the chart above, we have adjusted the quarterly revenues compiled by IDC for inflation to give a sense of the relative investment in 2020 dollars that companies were making back through the past two decades and a little beyond. As you can see, every other quarter in the late 2010s and into the early 2020s is like its own personal Dot Com Boom, and shipments have tripled as the world has moved from big RISC machines to smaller X86 machines — and a lot more computing is being done because of the price/performance increases.

There are a lot of reasons why server units can stay flat (or even rise) as revenues decline, and this happens from time to time. But considering that the market is consuming big, fat, GPU-laden baby supercomputers packed into a server chassis, thus pulling up the average selling price, there has to be some kind of shift going on to make server revenues drop.

IDC says that in Q2 2021 sales of high-end machines — those costing $250,000 or more — fell by 32.7 percent to $1.3 billion, and this is expected given that IBM was known to be readying its launch of the big, bad “Denali” Power E1080 server, which it did this week, as well as to be putting the finishing touches on its “Telum” mainframe processor and its System z16 servers for next year. There will be a revenue spike or two as these hit the market. SAP HANA in-memory database workloads drive a certain amount of big and expensive NUMA server sales, no matter where the Hewlett-Packard Enterprise Superdome Flex and IBM Power Systems and System z product cycles are at. And these and the remaining few other big NUMA machines in the market rake in the bucks supporting big databases and their back-office enterprise resource planning (ERP), customer relationship management (CRM), and supply chain management (SCM) suites. But given the product transitions at IBM and the coming machines, a slowdown at the top was expected.

Significantly, there was also, says IDC, a slowdown on sales of so-called midrange servers, which cost between $25,000 and $250,000, with sales off 30 percent to $2.4 billion at the same time that volume server sales — those that cost $25,000 or less — rose by 5.6 percent to $20 billion. The evidence is circumstantial, the causation is perhaps coincidental, but small machines are rising against the tide even though they cost a lot less per unit of compute.

We will try to get finer-grained data out of IDC and Gartner about this trend.

It is interesting to note that shipments of machines directly to hyperscalers and cloud builders from their original design manufacturing (ODM) partners fell by 5.2 percent to 1.04 million units, and revenues fell by 8.8 percent to $6.31 billion. Now, in many ways Inspur, Lenovo, Sugon, and Dell act like ODMs, so the IDC ODM figures are not a perfect proxy for hyperscaler and cloud builder spending.

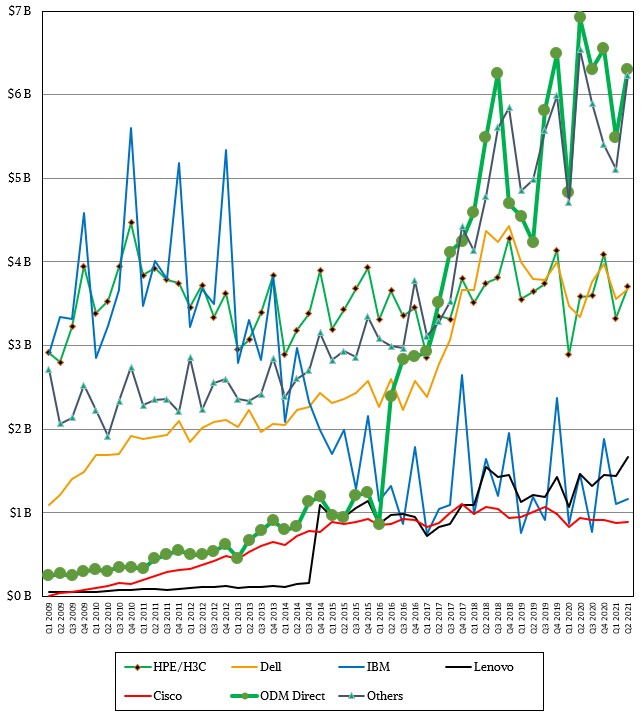

Here is a chart that shows vendor revenues over time since the Dot Com Boom in 1999:

And here is a summary table for those of you who like to see the data, which contains the four quarters of 2020 and the first two quarters of 2021:

The historical data in the vendor revenue charts has not been adjusted for inflation, but there certainly is some effect even going back to the Great Recession in 2009.

Hewlett-Packard Enterprise and Dell continue to battle for dominance, Inspur has lost a little heat, IBM is hanging in there as the number four revenue maker, and Cisco Systems doesn’t make the top five cut even though we have done our best to estimate and put it back into the table because Cisco is an important server maker in the enterprise. (The bold red figures in our tables always mean we are making an estimate in the absence of data.)

Now, once again, without further ado, is one of our favorite charts that we have ever built, which shows the relative price/performance of server capacity by quarter (adjusted for inflation, on the left axis) plotted against the aggregate amount of relative performance in the total number of servers shipped each quarter (on the right axis). Nice exponential curves showing the elasticity of consumption since 1999:

Note: This is not data from IDC, but rather data we have created using raw shipment and revenue data from IDC over more than two decades. There are some assumptions in here, but we think they are fair. Capacity is just incredibly less expensive, and capacity installed has grown in response to those Dennard scaling and Moore’s Law improvements over the decades and the increasing computerization of the world.

Comments are closed.

Q; IS THE SHIFT TO SINGLE-SOCKET SERVERS STARTING?

Not taking into account 2P board single processor implementation however viable, on WW open market processor broker/dealer, VAR and resale data;

AMD Single Socket Naples equals 5.9% of this full run; 18% of all 32C, 36% of all 24C, 18.7% of all 16C.

Single Socket Rome equals 29% of full run; 15.85% of all 64C, 11.4% at 32C, 21.54% at 24C, 24.82% at 16C, 10.2% at 8C.

Rome ‘F’ derivative large cache grade SKUs (that are 2-way) all core counts 24/16/8 = 2.54%

Single Socket Milan currently equals 6% of full product line where only 7543P 32C is available from the open market channel.

Milan ‘F’ derivative large cache grade SKUs currently only 16 and 8 cores are available from the open market channel = 12%.

Cascade Lake ‘Gold’ Uni = 0.0016% of all Gold SKUs and when added to Silver and Bronze although the aforementioned are 2-way capable total 23.15% of the Cascade Lake + CL Refresh full run.

Ice Lake Silver 2-way currently account for 33.29% of full line grade SKU volume.

Coffee E 22/21xx_ uniprocessor full run equals 1% of Skylake + Cascade Lake + R full run combined.

For the week only ending September 12, V6/5/4/3 E3 12xx open market channel available is 7.2x more than Coffee E available.

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

Ampere Computing is leading the way in this market with their 80 and 120 core processors for the cloud.

How big is this single socket market ? CSPs and OEMs