IT organizations, especially the key hyperscalers and cloud builders, don’t buy point products, they buy roadmaps. And they pay for them, too. And the precise focus that AMD has brought to bear in its eight year turnaround has made it have the most credible and expansive CPU product line for datacenter compute, it is getting its GPU compute act together, and it now has FPGAs from Xilinx and DPUs from Pensando to add into the mix.

All of this was on full display at the Financial Analysts briefing this week, which we listened to keenly. As you might expect, chief executive officer Lisu Su and her team spent as much time talking about money as they did technology, this being a meeting to convince Wall Street of the bright future that AMD has in the next four years or so. It is hard to see much beyond that, given the pace of change and the technological challenges that all semiconductor makers and their system builder – and by system, we mean compute, storage, and networking – customers are facing. The end of Moore’s Law, supply chain issues caused by increasing demand and aggravated by an ongoing pandemic, political jousting, and war.

It’s a lot. But the demand for compute is so insatiable that you can count on it like death and taxes. And if AMD can stay focused and execute on its roadmaps, then it has a very good chance of becoming the player it has always wanted to be in the datacenter: A true rival to Intel, like Sun Microsystems was to IBM two decades ago. Not just in technology, but in revenues and profits. And while AMD spent a lot of time talking about roadmaps yesterday, we are going to jump to the chase scene now and talk about the money and then do a donut and return to the roadmaps in a follow-on story (which we have finished and which you can now see here). So buckle up, we’re going off road.

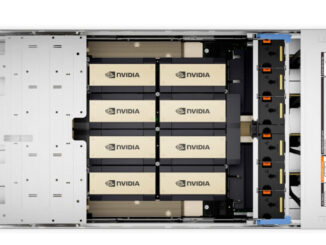

“When we first started our datacenter march, we said we were going to deliver three generations, and by that time, we would have leadership in the industry and customers would recognize that,” Su said in her keynote opening. “We are now in our third generation with “Milan,” we have absolute leadership in the industry. If you look at that from a performance standpoint, performance per watt and efficiency standpoint, total cost of ownership standpoint, it is recognized by customers. And what that means is, we are very, very fortunate to be in the world’s ten largest hyperscalers. It’s a great place to learn about where the market is going in the future. We have also had very strong traction in the enterprise market, and we have doubled that business year over year as well. And then when you put our CPU technology together with our datacenter GPU technology, the Instinct, MI200 series, what you see is that we can actually deliver the best computers in the world.”

And of course, Su called out the 2 exaflops “Frontier” supercomputer, based on AMD CPUs and GPUs as the prime example of this.

“AMD delivered the highest performance supercomputer in the world with Frontier,” Su continued. “It was the top of the Top500 list, it was the top of the Green500 list. And it was the top of the HPL-AI list. And not only that, but we are the first company to deliver an exaflops worth of computing horsepower. And I can tell you, it absolutely was not easy. It was not easy at all. But it was a long term vision. I mean, we set out on that path to break the exaflops barrier almost ten years ago.”

Frontier is many things, and will do much science, but it is probably one of the most cost-effect marketing campaigns that AMD has done – much as past supercomputers have been for Cray (now Hewlett Packard Enterprise, the actual builder of Frontier), Nvidia, and IBM in recent years. Even if AMD doesn’t make any money on it, years of people talking about Frontier and the fact that it was delivered during the pandemic and posted a 1.1 exaflops rating on the High Performance Linpack test has made it all that much easier to sell HPC and AI machinery to the world.

AMD went from a “second source to leadership performance” in the PC market, which has driven sales, it captured the custom silicon in Microsoft and Sony game consoles away from IBM, and it set its sights on the datacenter that it had abandoned like an old mining town in the late 2000s.

Frankly, it has taken three generations and the Xilinx and Pensando acquisitions – and Intel stumbling again and again on backroads using its crinkled up Xeon XP roadmaps – for AMD to be fully trusted in the datacenter. And now, AMD is going to really start hitting its financial stride, according to Su.

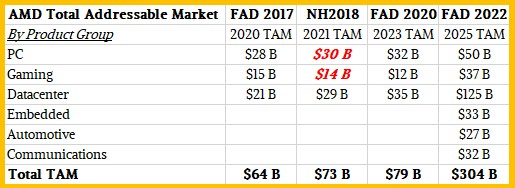

Part of AMD’s growth is coming just from the widening of its datacenter portfolio and its expanding total addressable market, or TAM. So, for fun, we went back to the Financial Analyst Day events in 2015, 2017, 2020 and the Next Horizon event in 2018 and compiled the TAM figures AMD revealed as it was getting its CPU and GPU businesses back on track thanks to the stern hand of Su. Take a look:

At any given time, AMD’s TAM figures are for the markets it participates in three years into the future.

Back at the FAD 2015 event, AMD did not even have the gumption to talk publicly about TAM, and it stuck to talking about roadmaps for its future Ryzen PC Epyc server processors and its future Radeon PC and Instinct server GPUs. That’s why there is no column for that in the table above. Su gave a datacenter TAM at the Next Horizon event in 2018, which was about stuff for the glass house, and we filled out what we think are reasonable TAMs for PC and gaming chippery for that in the table above. Two years ago, as Epyc and Instinct were getting traction, the future TAM for 2023 expanded a bit to $79 billion.

But now, with Epyc processors handily beating Intel’s Xeon SPs and future hyperscaler and cloud Epyc variants coming with more cores and fewer (unnecessary) features to give room for those cores (thus blunting some of the advantages of the Graviton Arm server chips developed by Amazon Web Services for its own use or of the Altra family for Arm server chips from Ampere Computing), and the addition of Xilinx and Pensando, AMD’s datacenter TAM has exploded, reaching $125 billion by 2025.

That is a lot of money to chase, and that is why we think that AMD will not be doing a lot of major acquisitions. The company might take a harder run at networking at some point, developing its own switch silicon to complement the Pensando DPUs, but that market is already crowded. And frankly, there is enough AI market to chase with Instinct GPUs and the DSP-based AI Engines and FPGA programmable logic from Xilinx. And the DPU buildout is just getting rolling, too. But, it may be that it is better to control the switch and the DPU together, as both Intel and Nvidia do with their respective networking chip.

So that gives a profile of the happy hunting grounds that AMD has been able to reach with its focused execution of delivering compute engines on time and with high performance and power efficiency against two very strong incumbents, Intel in CPUs and Nvidia in GPUs, who are both getting ready to raid each other’s strongholds – Intel with “Ponte Vecchio” Xe HPC GPUs and Nvidia with “Grace” Arm server CPUs. All three vendors are putting together hybrid CPU-GPU complexes for the next year and beyond, too, which we will discuss in detail in our roadmap discussion.

The TAM is a kind of rough financial roadmap that guides the product roadmap, and the quarterly financials tell you how much progress you are making on the trip. AMD’s progress has been steady, up hill and to the right, and as more than a few commented during the FAD 2022 event, it has been fun to watch. We have always believed that AMD could turn it around and that Intel needed something to push it, as all unregulated near-monopolists do. We don’t have a problem with monopolies, as we have pointed out before. But we do have a problem with them being unregulated, either by the market or by some other outside force. It is far better for competition to do the regulating than to have the Antitrust Division of the US Department of Justice do it. So Intel should be thankful. . . .

Back at the FAD 2017 event, at the beginning of the Epyc rollout and when AMD’s GPU compute story was weak, Su & Company had to be vague and promised “double digit growth” for revenues, gross margins in the range of 40 percent to 44 percent, and something resembling free cash flow through its balance sheet. AMD did 4 percent of revenue as free cash in 2019, 8 percent in 2020, and 20 percent in 2021.

At the FAD 2020 event, after three years of respectable but not yet huge Epyc sales and an improving prospect for GPU compute with the future MI100 and MI200 series, the company promised around 20 percent growth in the coming years, higher than 50 percent gross margin, and free cash flow of 15 percent or more of revenues.

Here at the FAD 2022 event, based on the pro forma combination of AMD and Xilinx (Pensando does not have material revenues relative to AMD or Xilinx), Devinder Kumar, AMD’s chief financial officer, says that AMD can continue to grow overall revenues at around 20 percent and get gross margins above 57 percent in the coming three to four years, and can also pull out somewhere north of 25 percent of revenues as free cash flow. As Kumar quipped, people have been asking when AMD will make some money. The answer is, starting now. In fact, we think that AMD is only gated by the amount of foundry capacity it can bring to bear from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. If AMD commissioned TSMC to make 2X the chips, it would sell 2X. The question then becomes how much capacity can AMD prepay for? That depends on its cash on hand. . . .

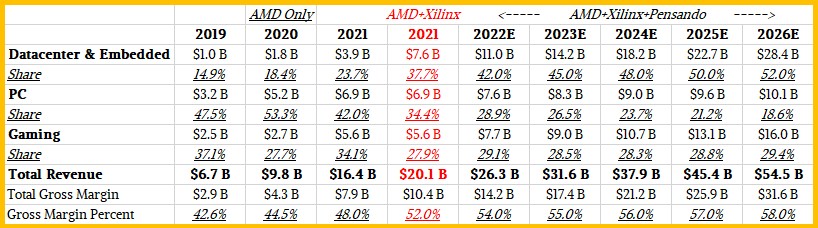

Su and Kumar said something else very interesting that plays into that equation, and that is in 2019 the Data Center and Embedded businesses, which will be two new separate reporting groups starting with the Q2 2022 financial reports but which were added together for this presentation, accounted for about 15 percent of AMD’s $6.74 billion in sales in 2019, or just a tad over $1 billion. By 2021, the core AMD business had $16.4 billion in sales, and just under $4 billion of that (our model says $3.9 billion) came from the Data Center and Embedded groups. Kumar called it around 25 percent, but it is 23.7 percent in our model. Now, if you add Xilinx to the 2021 numbers, then AMD’s 2021 revenues were $20.1 billion and about 40 percent of that, or around $8 billion, was for the Data Center and Embedded groups.

The projection looking out three to four years is for Data Center and Embedded to be above 50 percent of AMD’s overall revenues.

If you plug this all, and AMD’s forecast of $26.3 billion for 2022, into a sheet and project it out into 2026, this is what AMD could look like:

Just take that in for a second.

In the model above, we projected modest PC growth of 10 percent per year, half the rate of datacenter growth and consistent with the idea that AMD can gain share even in a down PC market because it is competing against Intel’s Core PC chips, which are bigger, hotter, and more expensive than AMD’s Ryzen chips. You can set an endpoint of Datacenter and Embedded being 50 percent of AMD revenues in 2025 and above 50 percent in 2026, and we assume the percentage will get harder to increase as the years go on. You can calculate Gaming revenues by subtracting these PC and Datacenter and Embedded chip sales out, and BAM! You have a rough revenue model for AMD for the next five years.

BAM, TAM, Thank You Ma’am

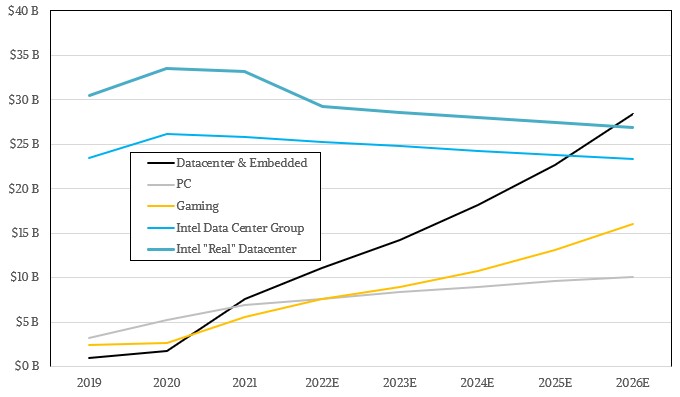

Now, here is where it gets really interesting. Intel is in the middle of rejiggering its groups and divisions and has not provided historical data for these new groups as yet. So we have to use historical data from its former Data Center Group sales and our own estimates of Intel’s “real” datacenter revenues, which includes sales of flash, networking, and various edge and IoT devices that ought to have been in Data Center Group but were not.

So for fun, we plotted the AMD historical data and projections (with Xilinx) that we came up with against Intel Data Center Group and our Intel “real” datacenter model. Take a gander at this:

Intel lost a chunk of datacenter revenue selling off its flash business in 2021, and it had a decline that year, too. And we think there is a good chance that Intel will not expand in the datacenter space going forward, and in fact, the chart above assumes a 2 percent revenue decline each year. Argue as you will, but Intel is the target and it is going to be hit on all sides and unless and until it gets its products to roll out on time, it is also gated by the foundry capacity it can line up and the availability of chips from AMD, Nvidia, and others like Ampere. If they can’t ship in high volumes because of insufficient wafer prepayments, then Intel will be able to hold the line. We are assuming they are going to pony up the cash and it gets harder for Intel. Not easier.

And thus, at some point towards the end of this projection horizon, AMD will have a datacenter business that is on par with that of Intel.

Crazy, isn’t it?

If the datacenter market expands fast enough, as it has in the past few years, then Intel can still do well. If the market contracts, then it is in a price war with AMD, Nvidia, Ampere Computing, and homegrown CPUs, and it will either have to sacrifice revenue (and profits) or sacrifice business. It is not clear what Intel will do in this situation, but vendors often walk away from such choices. Much to their chagrin years later.

But we know what AMD will do: Stick to its roadmap and drive to those mountains of money off in the distance. Look at that free cash flow! AMD will be able to afford a foundry of its own again – but won’t be tempted to go down that road to sorrow. It’s better to help TSMC pay for one and rent it like a cloud.

From AMD Q1 report:

For the full year 2022, AMD now expects revenue to be approximately $26.3 billion, an increase of approximately 60% over 2021.

You’re right. I forgot that. Tweaking the model.

Maybe AMD can finally start paying a dividend in a couple of years.

unlikely. AMD is aggressively buying back its shares and more important, it needs every penny it can spare for wafer agreement with TSMC

The crazy part here is no one is commenting on how hyperscalers operate or the obviously inflated ideas around AMD GPUs

Intel has already been delivering FPGAs to MSFT’s Brainwave project for several years. They already create DPUs for Google. They already have extended temperature XeonD chips for 5G edge processing and the NFV software developed, with big customers.

Now they are introducing data center GPUs, including ones that do AV1 hardware encode at 50x the performance of software implementations.

Their SPR-HBM chips are demonstrating 2x to 3x performance boosts in HPC workloads vs the Ice Lake Xeons. They recently entered the Bitcoin processing market with a leading performance chip and announced an Habana 2 training ASIC that improves performance by 3X over the first generation chip. So, whatever they were doing in the past, they don’t seem to be stumbling currently.

And yet Intel stock continues to flounder as it has for much of the past 20 years as investors have grown tired of its repeated failures to deliver compelling innovation and, more importantly, strong revenue and profit growth (it has a consistent and decent dividend which has value given the current bear market). AMD, Intel, Nvidia, Qualcomm, and many more are largely executing evolutionary technology strategies–PCIe, DDR, HBM, Ethernet, NVMe / flash, and so forth.

To a large extent, Intel’s failures are self-inflected while the others’ successes are due to disciplined execution of their respective strategies, i.e., the delivered what they said they would do after actually listening instead of dictating to their customers. Intel will eventually course correct, but by then, they may be relegated to just one of a multitude of suppliers which, IMO, would ultimately be best for the industry and customers. Far, far too often both have suffered as has innovation due to Intel dictating or playing kingmaker, e.g., just look at all of the innovative technologies they’ve marginalized or killed off or ultimately failed technologies they’ve foisted onto the industry / customers simply because of their unfortunate market dominance.

very useful article. Thank you

I have been involved with AMD multiple time throughout my 40+ years in the industry. Never before has it looked and acted in such a focused an determined fashion. I would definitely back AMD to achieve its growth and profitability plans for the future, allowing for events out of its direct control such as geopolitical, pandemic etc…..

Amongst all the data in this very longwinded article is a single statement that summaries the status of the semiconductor industry and the Electronics industry overall … “ If AMD could “manufacture ( via TSMC) 2X devices then it would sell them”.

That applies to most Semiconductor companies today and illustrates the pent up growth that is waiting to be released.

The war between AMD Intel Nvidia TSMC etc will eventually bear down on who will triumph on efficiency in deploying and using capital, ie who will waste less money on useless unproductive causes; Although the nature of high tech business is gambling with weighing odds against payoff, for Intel TSMC GF and Samsung etc, fab business is also a game of modern manufacturing dexterity. As of now, non-Asians are losing this battle to Asians. Enemy’s loss is warriors gain, AMD is sailing to its 2026 TAM goal soundly.

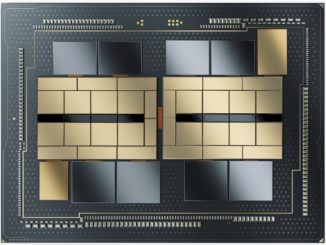

AMD’s unsung hero is Infinity Fabric IMO.

If amd put a monolithic 7nm 8 core against intel’s 14nm 8c, it would probably lose, even up to alder lake.

But rather than a fancy cpu core unit, they built a simple but scalable core unit – scalable using the all important Fabric.

A roadmap focus on perfecting Fabric, has simplified progress and validation & allowed unprecedented advances.

This is what observers overlook. They didn’t succeed on intels failures, they just got a boost for the inevitable result.

NV & Intel cant belatedly invent a sexy name for chiplets & fast track their own Fabric equivalent – its has been a decade or more incubating & has a family of custom designed, compatible processors – now including FGPA & GPU.

Even assuming intel can match core numbers in servers, they cant match the vital efficiency of Fabric to act coherently.

This i suspect is the reason for intels delays – when they cobble together a ~competitive number of cores, they are just not in the race with co-ordinating them vs Fabric.