One of the founding premises of this publication is that companies want to build platforms – complete stacks of hardware and systems software – or use those built by others that are tailored specifically to run their applications. In days gone by, these platforms had names like IBM System/360 or Digital VAX or Windows on Intel and they ran inside the corporate datacenter. It is now safe to say that, nearly a decade since launching its first product, Amazon Web Services has become a platform in its own right.

AWS is hosting its fourth annual re:Invent conference in Las Vegas this week, an event that has over 19,000 people on the ground and another 38,000 viewing sessions over the Internet. Amazon is obsessive about metrics and as usual, during his opening keynote address, Andy Jassy, senior vice president in charge of AWS, provided some statistics about the growth of Amazon’s cloud and talked about how an increasing number of enterprise customers were either going all-in with AWS or at the very least hybrid, using cloud capacity for a significant portion of their workloads.

While public cloud rivals Microsoft, with Azure, and Google, with Compute Engine, have much deeper pockets than Amazon, which has struggled for profitability as the retailer expands into new markets and services, thus far they and smaller rivals have not been able to match the breadth and depth of services that AWS provides. That is not to say that they won’t be able to do so eventually, but Amazon is a relentless innovator, has a significant lead, and is absolutely committed to the idea that AWS can rival the Amazon retail business in its size someday. (“In the fullness of time,” as Jassy likes to say, but did not say today at re:Invent.)

Jassy cited statistics from Gartner analyst Lydia Leong, who put together the latest Magic Quadrant rankings of infrastructure as a service providers back in May and who reckons that Amazon now has ten times the infrastructure capacity as the next 14 public cloud suppliers of raw infrastructure combined. Nine months ago, Jassy reminded everyone, AWS was said to have only five times the capacity, so the gap is widening even as Microsoft and Google spend billions of dollars on datacenters and the servers, storage, and switches that turn them into clusters for running virtualized applications. Gartner did not provide any estimates of the scale of the infrastructure at AWS, but Leong estimated last year it was around 2.4 million machines. We estimated that it is somewhere between 1.4 million and 5.6 million servers, based on a talk by James Hamilton, the distinguished engineer in charge of infrastructure at AWS, and reckon the number of servers in the AWS fleet in early 2015 was somewhere between those extremes at around 3 million machines.

AWS has over 1 million active customers, a number the company confirmed earlier this year and that Jassy reiterated in his presentation today. That customer number, which does not include Amazon itself, means someone who has paid for capacity for one of its services in the past 30 days, and the number is going up at an increasing rate in recent years. But it looks like the capacities for basic services on AWS have been going up even faster, which implies that many customers are coming back for more.

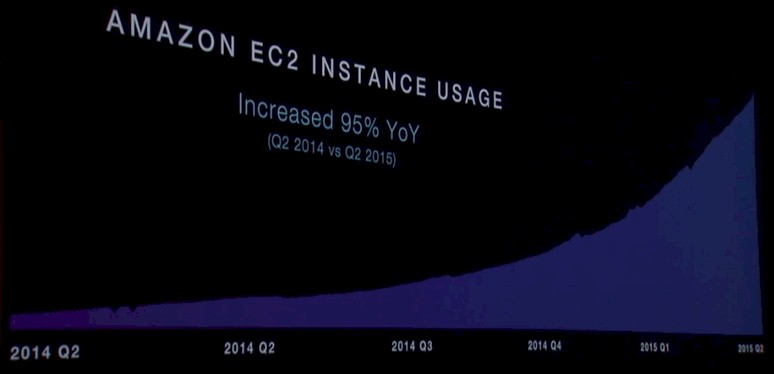

AWS measures EC2 usage in normalized instance hours per week, and the chart above obviously cuts off some of the bottom of the represented data because Jassy said that EC2 instance usage was up 95 percent in the second quarter of 2015 (the far right of the chart) compared to the second quarter of 2015. (In the chart above, “2014 Q2” appears twice, and obviously the first one was meant to say “2014 Q1.”) In any event, having a nearly factor of two increase in EC2 instance hours per week over a one year span is pretty healthy growth. It would be fascinating to see the same chart done on the basis of aggregate compute capacity used by customers in the AWS fleet and to see how much spare capacity it has, but AWS will never reveal such information. It would help its competitors figure out how to do a better job taking on AWS.

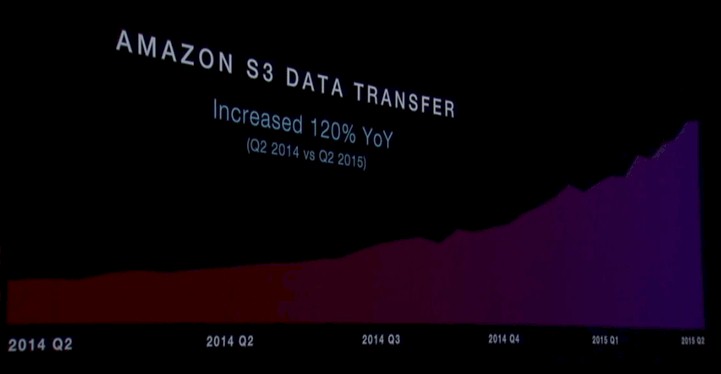

For many years, AWS used to give out the count of objects in its S3 storage service, two years ago it added an automatic deletion feature to S3 as well as offloading of S3 files to its Glacier cold storage, and that would no doubt make the S3 data take a dip. (This was intentional, and designed to save customers money.) So instead, AWS uses the data transfer bandwidth into and out of S3 as a proxy for capacity, and as you can see below, it is growing:

In fact, S3 data transfers are growing very fast. In the fourth quarter of last year, S3 data transfer capacity was up 102 percent year on year, and in the second quarter of 2015 it was up 120 percent compared to the year-ago period.

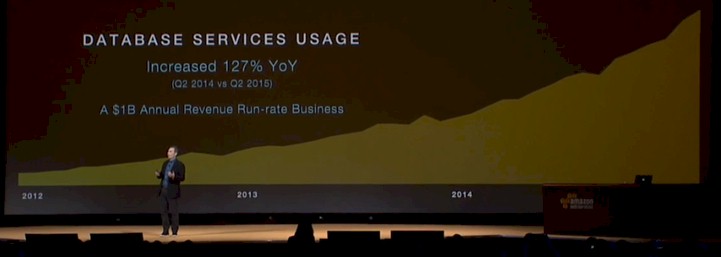

AWS does not just sell raw compute, storage, and networking infrastructure, but also has a variety of platform-level services that it sells on top of this infrastructure. Database services were among the first of these platform offerings from AWS, and here is how they are growing:

Jassy was not explicit about what metric was being used to gauge the database platform services usage on AWS, but what he did say is that these services together now have an revenue run rate of $1 billion a year.

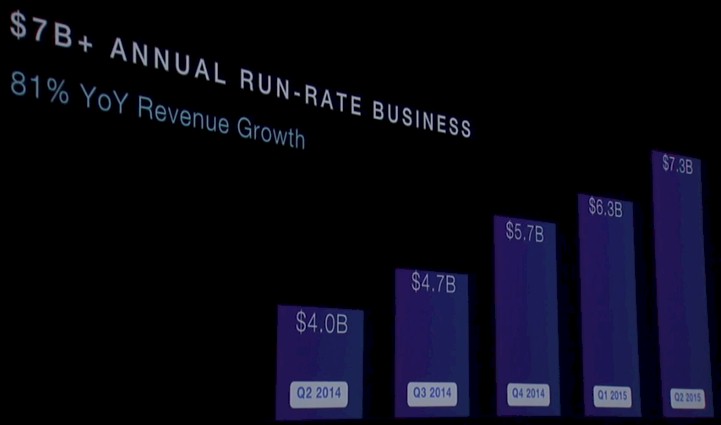

This, as it turns out, is a pretty big chunk of the revenue that AWS books. As the following chart shows, AWS had an annual run rate of $7.3 billion in revenues across all of its services in the second quarter of this year, which is an 81 percent increase in that run rate compared to the $4 billion level in the year-ago period. Other services are also driving AWS revenues, like the AWS Marketplace, a catalog where customers can deploy 2,300 applications from over 800 software vendors on top of AWS infrastructure. In the last quarter, over 143 million hours of EC2 instances were burned by these SaaS offerings, up 120 percent year-on-year.

Having the infrastructure is but one part of the growth of AWS, of course. It is the table stakes, but it takes more than that to have over 1 million customers, which Jassy said included around 2,000 government agencies, 5,000 academic institutions, and 17,500 non-profits. (We would love to know how many are large enterprises with more than 5,000 or so instances running in the AWS infrastructure, personally.) AWS also has thousands of systems integrator partners, who help enterprises move some of their applications to the cloud, and in some cases, move all of their infrastructure to the cloud. Jassy did not say how many of these “all-in” customers were on the AWS cloud, but everybody knows that Netflix was the first one six years ago and that the number is growing.

But for now, despite the fact that AWS does not believe in private clouds, hybrid infrastructure that is a mix of on-premises gear and its own public cloud utility is what seems to be driving its large enterprise revenues.

General Electric, the $149 billion manufacturing conglomerate founded by Thomas Edison 140 years ago, is a prime example of the large enterprise that is embracing a mix of on-premise and public cloud computing, with AWS as its cloud partner. The company makes all kinds of equipment, from aircraft engines to locomotives to lighting systems to wind turbines and it is adding all kinds of sensors and analytics to everything that it sells.

“For us, this is no longer an experiment. It is no longer a test. It is no longer something that we talk about as being probable. It is inevitable. We are moving, and we are glad to have AWS as our partner.”

“Industrials have to become digital to thrive going forward,” explained Jim Fowler, chief information officer at GE, in the keynote address. As examples, Fowler talked about a software-defined wind farm that us self-optimizing based on surrounding weather conditions that can generate 10 percent to 20 percent more electricity than wind farms without such smarts. Fowler said that telemetry from its assembly lines in its manufacturing plant in Greenville, South Carolina was being mashed up with product data from the simulation and modeling systems that create its products to allow for new parts to be introduced for manufacturing around 20 percent faster and will save GE over $1 billion over five years.

Fowler said that by 2020, GE will make $15 billion in revenues from software, and that this will make it one of the top ten software companies in the world.

The transformation at GE is not just adding software to products, but making use of data to provide services for those products.

“As you can imagine, as a company that is 140 years old, we have a lot of sins of the past that we have to deal with, like many of you,” said Fowler. “We have got 9,000 applications that we use across our business every day. We have over 300 ERP systems that are running our business, and too many physical datacenters to talk about. We have really had to look at what we have to change in our environment to enable us to become the leading digital industrial in the world.”

GE currently has over 2,000 locations on its network, but every jet engine and train will be a network location from now on, so its network has to change to accommodate all of these mobile devices as well as things such as power plants in the desert. GE has to get rid of bespoke systems in its datacenter and move to more modern, virtualized infrastructure that scales, too. And it needs to reinvest in people and build its own software again. “”Like many of you over the last ten years, we outsourced way too much,” Fowler said. “So part of this is retooling our own environment and in the last two years we have hired over 2,000 IT professionals, bringing knowledge capital back into GE.” The company is also investing $1 billion in a software design center in San Ramone, California to build applications.

To help pay for all of this investment, GE is moving about 60 percent of those 9,000 workloads to AWS over the next three to five years. And Fowler gave an example to illustrate why.

The part of GE that sells equipment to the oil and gas business has migrated over 50 percent of its application workload into AWS. One of the applications was a quoting and configuration tool that salespeople used in the field. It cost around $62,000 a year to run this application in GE’s own datacenters and it generated something on the order of $600,000 in orders; any time GE wanted to make a change to this application, it took around 20 days to accomplish that. After moving this application into AWS, this application cost $6,000 per year to run, code changes for it can be deployed in under 2 minutes, and the application is more available and works better, too.

As part of the consolidation, GE is going to be closing down 30 of its 34 datacenters. “And those four datacenters will only hold what we value most – our secret sauce that differentiates us – and everything else is going to AWS,” Foster continued. “For us, this is no longer an experiment. It is no longer a test. It is no longer something that we talk about as being probable. It is inevitable. We are moving, and we are glad to have AWS as our partner.”

How many CEOs heard that, and how many CIOs will be saying something similar in the next five to ten years? Tens of billions of dollars in IT spending a year are at stake.

Be the first to comment