When Lenovo Group bought the System x division from IBM last fall, it got a lot more than a business that sells rack and tower servers based on X86 processors. The company secured reselling licenses for core IBM systems software used in the supercomputing arena, and Lenovo also now employs some of the top high performance computing experts from Big Blue in various fields – including domain experts in the energy, finance, and manufacturing sectors. Lenovo takes HPC seriously, and equally importantly, it wants to leverage that HPC expertise in the enterprise and hyperscale spaces.

“We have a core team that really loves and wants to drive HPC,” Scott Tease, executive director of Lenovo’s HPC business, tells The Next Platform. “There is a deep belief here that innovation starts inside of HPC, and then makes its way out to the enterprise. Not all innovation starts in HPC, of course, but new technologies are forged by organizations that are willing to take risks, willing to do something a little bit different from everybody else.”

Tease was director of high performance computing at IBM for 14 years. Joining him on the systems team at Lenovo is Brian Connors, another former IBMer who was general manager of the IBM consumer PC business back in the late 1990s and who then moved on to take charge of IBM’s custom Power processor business for game consoles before moving over to be general manager of IBM’s overall HPC business in 2010. Connors is now vice president of enterprise systems development at Lenovo. Chris Maher, who was a director at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center several decades ago and who in charge of software development for the HPC segment at IBM for close to 15 years, now runs the software development business for Lenovo’s Enterprise Systems group.

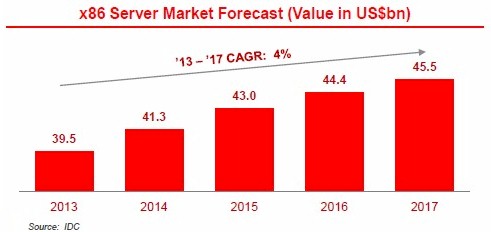

With the HPC segment being one of the fastest growing parts of the X86 server business, it is no surprise that Lenovo was interested in acquiring the System x business as well as rights to Platform Computing cluster management and Java messaging stack and to the General Parallel File System (GPFS) that is used as the storage layer in many supercomputing clusters today. Citing data from IDC, Adalio Sanchez, general manager of the Enterprise Group at Lenovo, said late last year that the HPC-related part of the systems business is growing at somewhere around 8 percent to 9 percent per year. That is roughly twice the growth rate of the overall growth rate of the X86 server business, which is expected to grow at about 4 percent per year between 2013 and 2017, according to IDC.

The Lenovo system business includes the various System x product lines from IBM as well as the ThinkServer rack and tower machines that Lenovo was selling prior to acquiring the IBM System x business last October for $2.3 billion. Tease said that this business accounts for about $4 billion in revenues per year, give or take, and reiterated Lenovo’s goal of boosting that to $5 billion “over the short term,” as Tease put it.

Lenovo is already the number three server maker in the world after the IBM acquisition, and it has a long way to catch the number two supplier, Dell, and even longer to topple the number one supplier, Hewlett-Packard. It took Lenovo ten years to build the combination of its own PC business and IBM’s PC business into something that competed with those of Dell and HP, and the company is taking a long-term view that it can repeat the trick in the server space – particularly because it has the design scope and supply chain scale that IBM was lacking.

The HPC business at Lenovo is pretty large, and like most HPC businesses, sales tend to fluctuate a lot depending on the X86 processor announcement cycle from Intel and what the capacity needs of the major supercomputing centers of the world are at any given time. Tease estimates that the total HPC business at Lenovo generates somewhere between $400 million and $500 million in revenues, and qualifies this as a ballpark figure. Within this revenue stream, about half comes from core HPC products, like the iDataPlex and NextScale density optimized systems, that were created specifically for HPC customers. The other half of Lenovo’s HPC revenues is driven by cluster sales based on traditional 1U or 2U rack servers or sometimes blade servers. (Those revenues cited above are for server sales and do not include software, switching, or storage.)

The hyperscale market is another fast-growing area, and one that Lenovo has some experience in back in China, which it hopes to leverage as it pushes into the market in the United States. when Lenovo talks about hyperscale, it means the big Web application providers like Google Yahoo, Facebook, and such, as well as the myriad cloud infrastructure providers like Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Compute Engine, and so forth. HPC and hyperscale share some common attributes in terms of system and network design as well as workload and cluster management. Lenovo reckons, based on data from IDC, that the revenues in the hyperscale/cloud part of the server business are growing somewhere in the middle teens per year.

On the hyperscale front, Lenovo has an existing business focused on the largest cloud service providers and hyperscale datacenters, and a business that Tease says does a couple of hundred million dollars a year in business. Roy Guillen, who was director of engineering for storage and servers at Dell, ran its Taiwanese design center for many years, and then did development for the Data Center Solutions custom server unit of Dell before becoming its general manager five years ago, has been running Lenovo’s Enterprise Group prior to the System x takeover and is now in charge of a hyperscale server unit that has just been formed to attack the hyperscale market in the United States.

“We are going to act like a startup inside of Lenovo,” says Tease, adding that the United States currently accounts for about two-third of the server volumes sold into hyperscale accounts worldwide. “IBM never had the cost structure and the supply chain machine to go after this business, but Lenovo definitely does.”

The enterprise segment accounts for the remaining revenue at the new enlarged Lenovo systems business, and about half of that enterprise revenue comes from rack and tower servers that are basically a commodity in the datacenter. The other half is driven by high-end NUMA machines, converged Flex System iron, or density optimized machines like the NextScale systems.

The trick, says Tease, is to realize that these markets feed back and forth into each other, and that is certainly the case with a proof of concept project that Lenovo has just initiated with the Hartree Centre, a supercomputing center in the United Kingdom. As The Next Platform has previously reported, Lenovo has partnered with Hartree Centre to create a prototype ARM-based cluster, based on Lenovo’s NextScale minimalist server designs and employing Cavium’s ThunderX 64-bit ARM processors.

Be the first to comment