So, who was the biggest revenue generator, and showing the largest growth in sales, for servers in the final quarter of 2016? Was it Hewlett Packard Enterprise? Was it Dell Technologies? Was it IBM or Cisco Systems or one of the ODMs? Nope. It was the Others category comprised of dozens of vendors that sit outside of the top tier OEMs we know by name and the collective ODMs of the world who some of us know by name.

This is a sign that the server ecosystem is getting more diverse under pressure as the technical and economic climate changes and vendors of all kinds evolve to adapt. Some are doing better than others, pulling back in markets and niches or forming partnerships, and others are eating market share in an effort to starve out their rivals. They all faced intense competition in 2016, and are looking for an even more contentious environment as the Cambrian Explosion of compute technology– including a herd of processors and coprocessors from Intel, AMD, IBM, Cavium, Applied Micro, Qualcomm, and Nvidia – is getting ready to storm the datacenter to eat their share of the juicy green money in those IT budgets.

The server market is more choppy than it has been historically. In the old days – like, twenty and ten years ago – processors were updated more frequently and server acquisitions were a bit smoother in that tens of millions of enterprises the world over would buy capacity based on their near-term needs. But the rise of hyperscalers, who provide online services to us, and cloud builders, who provide raw and cooked infrastructure services to enterprises, has caused the market to behave a little more arhythmically while at the same time market share changes are leveling revenues out across the year.

Let’s take a look at some pretty pictures and talk this through.

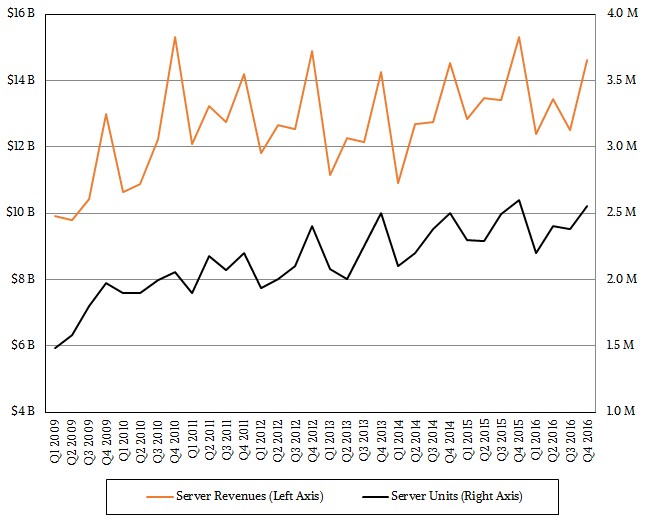

Hyperscalers and cloud builders buy machines in lots of tens of thousands, and they account for roughly a quarter of server shipments worldwide, depending on who you ask. Call it around 600,000 units a year, more or less. If these organizations decide to put a new datacenter or a server refresh or buildout in an existing one on hold for a quarter, it really messes with the quarter shipment and revenue figures. Throw in an expected and dramatic processor upgrade cycle a few quarters in the future, and it is no surprise that the server market took a slight pause in the final quarter of 2016.

It is important to remember that a slowdown like we are experiencing now is not a disaster. The decline in server shipments and revenues in the fourth quarter of last year, data for which is just becoming available now, is almost an order of magnitude smaller than the sheer dropoff we saw in server spending in the belly of the Great Recession back in late 2008 and early 2009. Perspective is important. And even then, server sales only fell by 30 percent to 35 percent for a few quarters; they did, however, take until 2010 to reach revenue and shipment levels attained in 2007, and it took another year or so to build up some momentum and get the market growing at a healthy pace again.

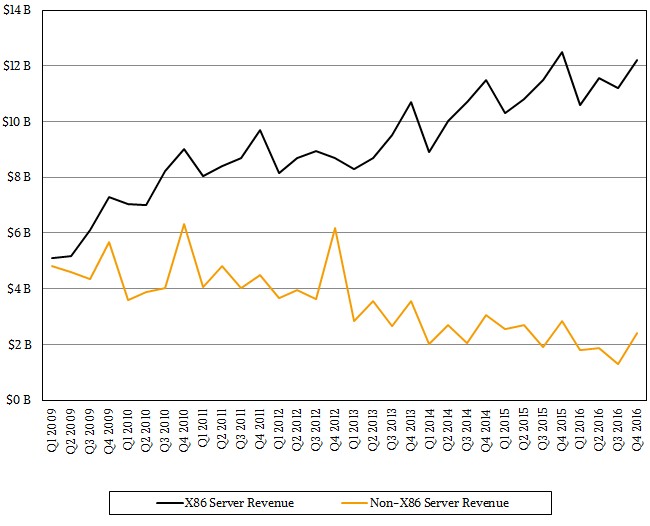

In Q4 2016, according to the box counters at IDC, server revenues fell by 4.6 percent to $14.61 billion, and shipments were off 3.5 percent to 2.55 million units sold worldwide. (IDC tracks shipments out of vendor factories, not shipments into customer accounts through direct or channel sales. These are slightly different figures, and some machines lag in the channel for a bit between quarters.) Sales and shipments of machines not based on X86 processors, have not shown growth since the fourth quarter of 2011 and are about half the levels they were at back in 2009. X86 servers, which since the Great Recession has meant almost exclusively Intel’s Xeon processors, have filled in the revenue gap and dramatically boosted shipment levels, but in the final two quarters of 2016 were in decline. There were some pretty tough compares with the final two quarters of 2015, to be sure, but it is also noteworthy that the market was anticipating a “Broadwell” Xeon update in the spring of 2016 and sales still motored on.

Something appears to be different this time around as we await the “Skylake” Xeons from Intel, and it is, we think, simply that the Skylakes will represent a significant architectural change akin to the “Nehalem” Xeon 5500 launch in March 2009 (right into the gaping maw of the Great Recession, by the way) and that AMD will be setting itself up to provide some real competition with Skylake in the X86 space with its “Naples” Opteron chips. It has been a long time since AMD was on the field, much less competitive.

That said, there is a lot going on all at the same time in the market.

“The server market suffered another difficult quarter as most segments declined, including hyperscale deployments, suggesting that the weakness previously seen is more systemic,” explained Kuba Stolarski, research director of Computing Platforms at IDC, in a statement accompanying the market states. “Some public cloud datacenter deployments are being delayed and there are indications that overall levels of deployment and refresh may slow down even through the long term as hyperscalers continue to evaluate their hardware provisioning criteria. On the enterprise side, we are seeing ongoing weakness as companies struggle to decide whether to deploy workloads on premises or off, and continue to consolidate existing workloads on fewer servers.”

In the quarter ended in December, X86 servers accounted for $12.2 billion in sales, down 2.4 percent, and 2.53 million units, according to IDC. That gave the X86 platform a 99.2 percent share of server shipments worldwide and an 83.5 percent share of revenues, which is about as good as it gets. If IBM stopped development of Power and System z chips tomorrow and Oracle and Fujitsu did likewise with their respective Sparc and Sparc64 chips and the ARM collective just fizzled out, and AMD did not deliver a credible Opteron alternative, it would take many, many years for Intel to get anywhere near 90 percent and then 95 percent of server revenues worldwide. We do not think, by the way, this will happen. Hyperscalers and cloud builders want alternatives and they have been flirting with ARM and Power chips to try to foster one. But AMD looks to be getting set to provide an X86 alternative that will be much easier for them to adopt. AMD won’t get 25 percent market share, as it had during its peak in 2006 and 2007 before Intel got Nehalem Xeons out the door, but if it can get the Naples Opterons – we don’t think they will be called Opterons – shipping in volume and get hyperscalers and cloud builders on board quickly, then there is no reason AMD cannot take 5 percent or 10 percent share in the X86 space in 2017. That is a whole lot more share than the 0 percent it has had for seven years.

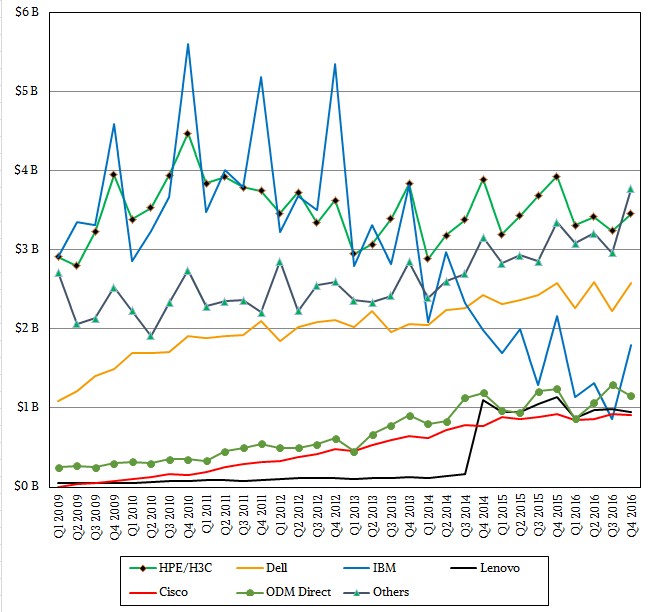

We find it interesting that the Others category – meaning not the top five OEMs plus the ODMs as a collective – generated the most revenues in the fourth quarter, and this is the first time we can recall this happening. As you can see from the chart above, the Others bopped along for a few years in the wake of the Great Recession and then started a slow and steady rise, due in part to the rise of whitebox server maker Supermicro and a handful of Chinese vendors such as Sugon, Inspur, and Huawei Technologies getting traction in their home Chinese market and carving into the share held by HPE, Dell, Cisco, and others in the Middle Kingdom.

We also find it interesting that the vendor curves above, excepting IBM, which is dominated by high-end iron, and Others, are flattening out. Lenovo has found a steady state of just under $1 billion in revenues per quarter, more or less in line with Cisco, and both are just a little behind the ODM collective, which is averaging about $1.1 billion sales per quarter. Dell is somewhere around $2.5 billion per quarter, and HPE is around $3.35 billion per quarter. So to one way of looking at things, the server market is fairly stable.

As we have said about the HPC and hyperscale/cloud markets for quite some time, perhaps it is wise to examine the market on an annual, rather than quarterly basis.

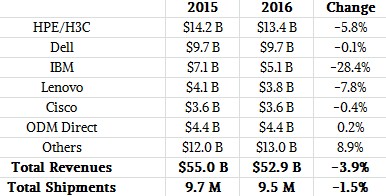

If you do that, then the server market had a 1.5 percent decline in shipments, to 9.53 million units, and revenues fell by 3.9 percent to $52.9 billion. Slowing sales of IBM’s System z13 mainframes as well as a decline in RISC/Unix machines across the few remaining vendors (IBM, Oracle, HPE, Fujitsu, Bull, Inspur, and NEC) definitely pulled the market down, with revenues off 25.9 percent to $7.4 billion in all of 2016. And the ODM collective did not help fill in that gap, with sales up a fraction of a percent to $4.4 billion. Dell was flat at $9.7 billion in sales, and HPE, the market leader, had a 5.8 percent decline to $13.4 billion, with the declines worsening as the year went on. In the X86 space, Dell had 21 percent of shipments worldwide and HPE had 20.5 percent, according to IDC, and obviously they have radically different average selling prices for their revenues to be so divergent. It looks like Dell is buying shipment market share with cheaper machines, taking on some of the ODMs perhaps and leveraging its complete PC and server supply chain to drive down its costs – something HPE cannot do because it no longer has a PC business and therefore has less leverage with processor, memory, and storage vendors.

Cisco is basically flat, at $3.6 billion in sales for 2016, and Lenovo fell 7.8 percent to $3.8 billion. Despite a harrowing 28.4 percent decline in 2016 to $5.1 billion, IBM still maintained the third pole position in the server space, and it is possible that someday Lenovo will catch it; Cisco probably will not. But the Others, as a group, did well in 2016, rising 8.9 percent to $13 billion in revenues.

With hyperscalers and cloud builders pausing, enterprises still sluggish with investments, HPC centers wondering about the political environment, and all organizations looking to squeeze more performance out of systems (did we hear containers there?), it is a good guess that getting revenue and shipment growth in 2017 will be no easy task. It could happen, but we would not bet on anything like the growth we saw in 2010 and early 2011 after the Great Recession or in 2015 with the Great Cloud Buildout. That said, even $50 billion to $55 billion in server iron is a lot of money to chase, and not a penny will be left on the bargaining table.

Be the first to comment