Anyone who thinks that Intel is easy to kill need look no further than the historical trends of the Mercury Research market share statistics that we see each quarter. Data for the third quarter of 2024 was just announced, and we have paired this with historical trends in shipments and revenues from Gartner to give you a sense of what the heck is going on with X86 CPUs in the datacenter.

To gather up this data, we had some help from Aaron Rakers at Wells Fargo Equity Research, who watches the semiconductor space like a hawk and loves building thorough and complex spreadsheets and charts and tables as much as we obviously do.

And, importantly, the Mercury Research data about X86 server CPU shipments and the revenue streams they generate show one important statistic: No matter how much AMD has gained, three quarters of the X86 CPUs supplied to the datacenters of the world still say Intel underneath their heat sinks.

AMD has been able to do better than that share on server CPU revenue streams, which is also interesting. We think that this is because the “Milan” and “Genoa” generations of Epyc processors, which are more heavily cored processors than the Xeon processors announced at the same time, are sold with better price/performance against higher throughput and make it up with higher average selling prices despite the deep discounts that the hyperscalers and cloud can command when they buy compute engines. And as enterprises are increasingly adopting AMD server CPUs, the revenues and margins for AMD and its OEM partners are also going up because these customers do not get the steep discounts that the hyperscalers and cloud builders do.

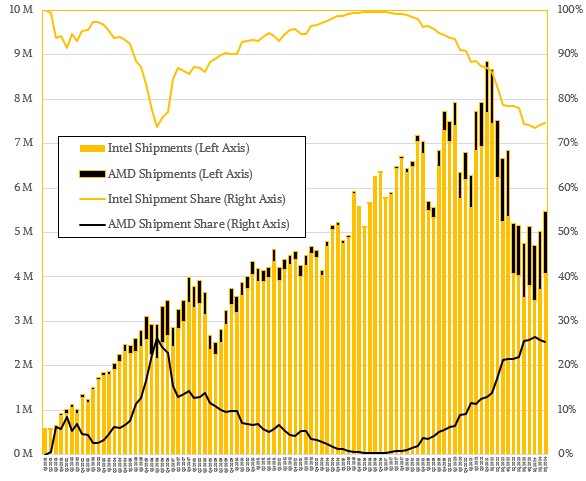

Here is the latest breakdown of AMD and Intel X86 server CPU shipments according to Mercury Research:

In the third quarter, Intel shipped 4.09 million X86 server CPUs, which was up 15.3 percent year on year and up 9.8 percent sequentially from the 3.55 million chips that the company got out the door in Q3 2023. As you can see from the chart above, which shows a kind of Mandelbrot fractal line chart of Intel and AMD market share overlaid on top of a bar chart of aggregate X86 server CPU shipments from Q1 2001 through Q3 2024, it looks like Intel bottomed out in Q3 2023 and again in Q1 2024, when it sold 3.46 million CPUs. Clearly, the “Granite Rapids” and “Sierra Forest” Xeon 6 processors are being better received than their “Sapphire Rapids” predecessors – at least from the early data. We will know more for sure when we see Q4 2024 and Q1 2025 data.

In terms of shipments, AMD actually grew slower than Intel in the third quarter of this year, but kept pace just fine. According to the Mercury Research data, AMD peddled 1.39 million Epyc processors in Q3 2024, up 14.4 percent year on year from 1.22 million CPUs in Q3 2023 and up 7.1 percent sequentially from Q2 2024. Total X86 server CPU sales in the period rose by 15.1 percent to 5.48 million units, which was also a 9.1 percent sequential bump.

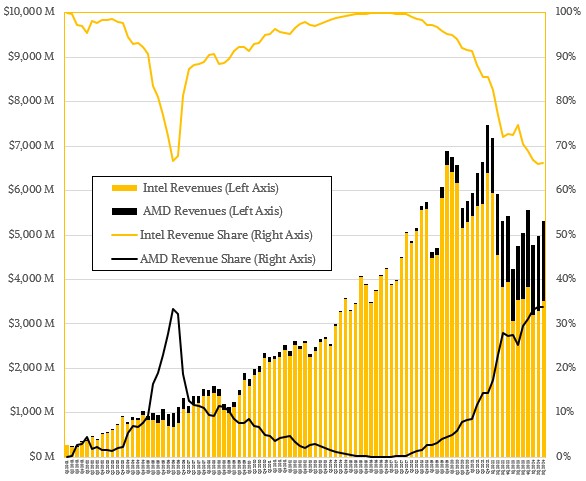

Now, when you start talking about money, Intel is not doing so well, and our financial analysis for Q3 2024 for Intel (see here) and for AMD (see there) showed this very clearly. Take a gander at the revenue streams from those X86 server CPUs over time:

In the third quarter, it looks like Intel Xeon server CPU revenues went down by 1.4 percent to $3.51 billion, which was nonetheless up 6.9 percent sequentially, matching the sequential revenue pace for X86 server CPUs overall. AMD has an easier compare because its market share was lower a year ago, and its Epyc CPU revenues rose by 20.7 percent year on year to $1.8 billion, but it also only had 6.9 percent growth sequentially. Overall X86 server revenues were up by 5.1 percent to $5.31 billion, according to the data compiled by Wells Fargo.

Once we have cased the relative positions of AMD and Intel in X86 server CPUs, what we then want to know is how are the revenues stacking up for the boxes that use those server chips. (There is obviously some lag in the data here, because a CPU sold in Q3 doesn’t necessarily end up in a server sold in Q3.) And thankfully, Wells Fargo has access to the Gartner server shipment and revenue data up through Q2 2024. The Q3 2024 data is not out yet because most of the server OEMs and ODMs have no reported their financial results as yet for the quarter ended in September.

Just because we can’t stand waiting, we have estimated shipments and revenues for Q3 2024 in the chart below based on historical trends and rising ASPs for machinery as more and more AI servers are sold by the ODMs and OEMs and sometimes by chip makers themselves. (Particularly Nvidia with its DGX line.)

If we assume that the average selling prices of servers stayed around the same in Q2 2024, then we think that $38.7 billion in servers were consumed in Q2 2024 against the 2.72 million machines that Gartner says were sold. (We are not sure why Gartner’s revenue data for Q2 was not in the Wells Fargo dataset, but we filled the pothole.) If you assume that ASPs are staying the same and that overall server shipments will map to the Mercury Research X86 server shipments above, then around 3 million servers went out the door in Q3 2024, driving $42.2 billion in aggregate sales worldwide.

That is a 13.9 percent increase in X86 server shipments and a 39.4 percent increase in X86 server revenues year on year. And this chart obviously ignores the growing numbers of Arm-based servers being deployed at the hyperscalers, cloud builders, and HPC centers of the world as well as a small steady state of relatively expensive Power and z mainframe systems from IBM.

The chart above shows Gartner data running from Q1 2002 through Q3 2024, including our estimates to fill in the potholes.

Here is one of the neat things about this data. You can see how much the average CPU represented of the cost of an average server over time. If you do the math, back in 2002, the CPUs represented around 10.5 percent of the cost of the system, and by the time AMD was strongly in the market in 2004 and 2005, with lots of cores and better designs than Intel, that rose to just above 15 percent of the overall server price. As workloads grew at hyperscalers and cloud builders, sales of higher-bin server CPUs helped raise the CPU share of the server to the low 20 percent range, and by the time AMD Opteron was pretty much vanquished from the market in the wake of the great recession, the lack of competition and the need to cram more compute in a box put that share well above 30 percent of the cost of the system.

If you are wondering why the hyperscalers and cloud builders want their own Arm server CPUs, there is your answer. In the absence of competition, Intel charged a very high price for its CPUs. And its financials in the 2010s show this.

By the late 2010s and early 2020s, AMD is back in the market, Arm server chips are a viable option, and customers are not in a mood to pay a lot for a CPU because in many of their servers they need to spend big bucks on GPU accelerators and advanced networking to build AI clusters. And so the X86 CPU share of X86 server costs plummets in early 2022 to below 20 percent of the cost of the system and has done a step function down again to about 12 percent in 2024.

This Gartner data also shows something else. The server shipment recession in the wake of the GenAI boom was much worse than the dip in server shipments in the wake of the Great Recession in 2008 and 2009. During the Great Recession, there were four quarters of double digit shipment declines and five quarters of revenue declines with four of those being double digits. (Revenues collapsed one quarter earlier than shipments did.) If the shipment levels had stayed constant at 2.2 million units in late 2008 and early 2009, then around 1.65 million more servers would have been sold. That removed something on the order of $5 billion in X86 servers from the market. You can see the hole in the chart above.

Because the hyperscalers and cloud builders are high volume and capricious server buyers, who tend to be at the front of the line for generations of CPUs, we actually see X86 server shipment recessions – meaning at least two quarters of consecutive decline – many times in the past decade. To be specific, we have three quarters of consecutive server shipment declines from Q3 2016 through Q1 2017, and another one from Q1 2019 through Q3 2019. There is a four quarter shipment recession that runs from Q3 2020 through Q2 2021. And there is a five quarter server shipment recession from Q4 2022 through Q4 2023 which absolutely coincides with the GenAI boom.

With the earlier server shipment recessions, there is often a quarter of revenue declines but not a true recession with two consecutive quarters of decline. Revenues get weaker nonetheless. But not in the GenAI boom, where ASPs keep growing and growing as the GPU, memory, flash, and networking content in AI servers keeps growing fast.

Anyway, if you assume an average quarter should see 3.2 million servers being shifted, then the shipment recession plus the last two quarters of below average shipments probably removed somewhere between 4.5 million and 6 million servers from the market to help pay for AI servers. That is probably on the order of $4.5 billion to $6 billion in general purpose machinery that was not sold. That is a much larger number of servers that were not sold than happened in the Great Recession, and very likely a larger amount of revenue lost, too.

The good news is that it looks like the underlying X86 server shipment recession ended in Q2 2024, which should help the profitability of both Intel (which needs it badly) and AMD (which also needs it). AMD won by gaining so much share, and Intel won by staying in the game despite the failures of its foundry, which made its products uncompetitive.

We look forward to seeing what happens in Q4 2024 and if Intel can reverse some of those difficult trends in the charts above. We still think that there is a high likelihood of a 60-40 or 50-50 spilt between Intel and AMD over the longest of hauls in the X86 server CPU space.

One last thing. The server recession has ended, but it remains to be seen when server shipments will get back to where they were before the GenAI boom started. With so many cores being crammed into a box and price competition for each core, perhaps this will take a long time indeed. Which again is great for customers.

Intel market share falling, but still 3 times larger than AMD. AMD profit is up, Intel is losing money hand over fist.

Intel must be really sucking wind in the foundry business, because they still sell a LOT of server CPUs. Still confused about how they can lose so much money while still in such a commanding position.

I think you answered your own questions, HA! Intel has to sell at or below cost to meet the price/performance competition against AMD, or it has much larger corporate overhead (that doesn’t get immediately allocated to operating income) and has to sell slightly above cost. Not sure which way it is.

I have been wondering what would have happened if AMD had made 3X the quantity of CPUs during the Milan and Genoa generations. Would it have wiped Intel completely out of the market? What does AMD know that we don’t? Are there still OEM customers who will not buy AMD CPUs no matter what? Seven years in, are there still people who don’t trust AMD? What are we missing here?

Since special features such as QAT offload built in to Intel processors is leveraged at the OS level, most x86 applications run on either Intel or AMD without trouble. The fact that two independent manufacturers would have to go out of business to stall future hardware innovation makes the x86 software ecosystem particularly robust. It also means–aside from preferred vendor status–their is little risk when corporate IT infrastructure switches between manufacturers.

While a 50-50 balance between Intel and AMD sounds ideal, such an equilibrium seems unlikely to be stable.

If AMD did not develop Epyc and Ryzen when they did, then ARM would be eating Intel’s lunch. In that case the x86 software ecosystem would undergo a crisis similar to what’s happening to Intel after which there would be less opportunity for recovery.

Hopefully the realisation my enemy has saved me is one of the reasons for the new joint x86 advisory board. If things go well then maybe x86 can avoid the mutually assured destruction of Softbank versus Qualcomm.

Exactly, and well said. I think 60-40 moving to 50-50 moving back to 40-60 and then back again seems poetic. Heaven only knows that is likely.

And yes, I think it is safe to say that AMD saved X86. But it may have to add RISC-V so it can crush Arm.

Am always left wondering why AMD doesn’t 3x its quantity of laptop chips, desktop chips, and server chips. How is say nvidia able to scale up to 30b in revenue with assumed a massive increase in h100 sales which would require a large supply but AMD is never able to no matter how competitive its product especially in the laptop space.

He who controls HBM controls AI.

“He who controls HBM controls AI”

Intel demoed a chiplet with 4Tb optical bandwidth using 8 channels of light per fiber… so 64 channels of optical pcie5 streaming with a single chiplet. Their current Gaudi 3 is using 24 x 200Gb IO on copper.

Some Aurora jobs process data that is streamed from the Advanced Photon Source. It is too big to be saved anywhere … so channel input data is already a streaming solution. The question is … why can’t model parameters and feature data be streamed and broadcasted instead of counting on all the hbm storage?

The whole article talks about servers and CPUs, not about cores, and not about consolidation, e.g. how many installed base is replaced by AMD (and/or ARM).

Can you translated “servers shipment” into cores? If -yes if- AMD is shipping on average 64 core cpus, and intel 28, than they can ship a lot more cpus and still end up shipping the same amount of cores. (And you could argue that server or cpu’s are sold, not cores, but there are multiple models available.)

Agreed. I used to try to figure this out, but it is a tough thing to guess.

Last paragraph says, “The server recedssion has ended, but it remains to be seen when serber shipments will get back to where they were before the GenAI boom started.” This needs to be fixed.

Yes. This is why you don’t type a last thought live into your story when you have the flu….

q3 server volume and share,

On channel on financial assessment, I have AMD Epyc at 1,365,593 units in q3 that is sufficient volume for the second half. AMD appears to have pulled cost out of q4 by producing a sufficient volume of Epyc and Ryzen performance desktop in q3 for the remainder of the year. All up q1 – q3 I have Epyc at 6,518,945 units produced.

I have Intel Sierra Forest and Granite Rapids at 1,119,000 units in q3 and approximately x2 (2.2 M) produced that is a rationale guestimate on SF and Granite suspect q2 and q3 ‘sample price’ reconciled on INTC 10Q DCAI so said revenue. Continuing Intel q3 plus 5,031,272 NEX associated Xeon for 6,150,272 DCAI + NEX units produced. For the year thus far, 15 M to 18 M units Xeon and in q2 it appears DCAI moved entirely over to ‘3’ production.

Component share I will offer up my complete take and then point to the full AMD and Intel reports subject encompassing assessment beyond the traditional syndicated sources of research and assessment.

Intel and AMD component share on q3 production,

Server; 81.9% and 18.1% and Mercury states 24.2%

Desktop; 57.5% and 42.4% and Mercury states 28.7%

Mobile; 77.4% and 22.5% and Mercury states 24.2%

All x86; 68.3% and 31.6% and Mercury states 23.9%

If you add AMD embedded accelerator into server, AMD gains to 20.5%

Intel and AMD component share on q3 channel data, server, desktop, mobile;

Mercury states AMD server at 24.2% and we rely on the same ebay channel supply data where I attempt to reconcile Mercury’s approach and here’s the result.

Server back to Rome and Cascade Lakes

AMD = 19.7% and Intel = 80.3%

Server back to Milan and Ice

AMD = 34.7% and Intel – 65.3%

Server back to Genoa and Sapphire Rapids

AMD = 44.6% and Intel = 55.4%

Mercury states AMD desktop at 28.7%

Desktop back to Vermeer R5K and Alder 12th

AMD = 34.4% and Intel = 65.6%

Desktop back to Raphael R7K and Raptor 14th

AMD = 50% and Intel = 50%

Mercury states AMD mobile at 22.3%

Mobile back to R7K and Raptor 13th

AMD = 20% and Intel = 80%

Mobile back to Alder 12th and Rembrandt R6K

AMD = 17.6% and Intel = 82.3%

Mobile dropping R6K but leaving Alder 12th

AMD = 11.7% and Intel = 88.3%

Mobile back to C5K and Tiger 11th H

AMD = 24.5% and Intel 75.5%

x86 Total

Mercury states 23.9%

Total back to RK6 mobile and Alder 12th

AMD = 23.6% and Intel = 76.3%

Total back to Sienna/4000 and R7Ks and Sapphire Rapids and Core 14th

AMD = 33.8% and Intel = 66.1%

Dropping Sapphire Rapids AMD gains to 36.7%

AMD full report is here in comment string:

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4731391-amd-q3-buy-the-dip-as-data-center-growth-is-what-counts

Intel full report is here in comment string;

https://seekingalpha.com/article/4731858-intel-corporation-intc-q3-2024-earnings-call-transcript

Mike Bruzzone, Camp Marketing

“We still think that there is a high likelihood of a 60-40 or 50-50 spilt …”

because AMD is leading the research on new technologies like AMX, AVX10.2, PCIE6, Optical IO, CXL?

For a lot of reasons, yes.

All of those examples were research that Intel initiated.

Support for MRDIMMs and their vRAN layer 1 acceleration are more examples. Intel puts years of R&D into these. Now they’re nearing products with with BSPD and, in a few years, glass substrates. And on the consumer side, they launched Thunderbolt 5 and WIFI7 IO this year. So, those are “lots of reasons” for Intel. What are the “lots of reasons” for AMD?