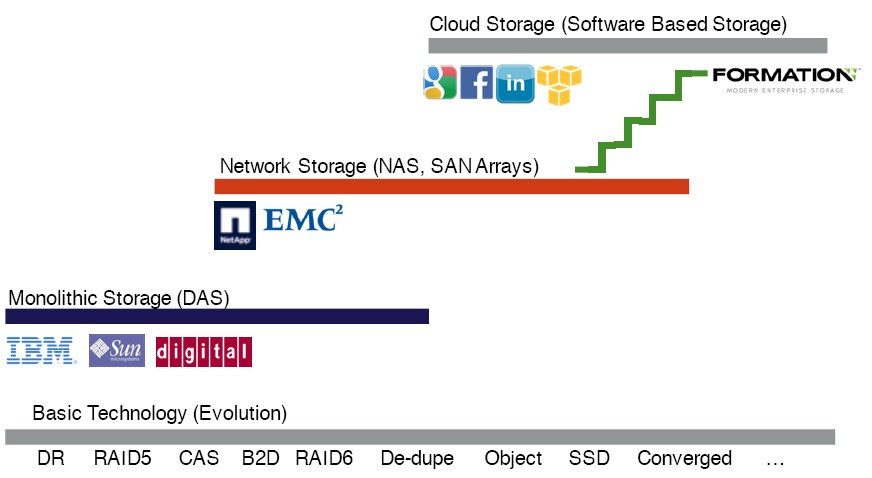

While compute and networking are fairly homogenous across the enterprise datacenter these days, the same cannot be said for storage, which is a bit of a mess and far less uniform than the clustered storage that is deployed by hyperscalers, cloud builders, and HPC centers.

Taking some inspiration from those scale-out architectures as well as open source object storage efforts such as Red Hat’s Ceph and OpenStack’s Swift, upstart Formation Data Systems wants to replace the racks and racks of disk arrays that provide block and file storage for enterprise applications. So do other object storage makers that have created block or file access layers for their storage, including those peddling Ceph as well Scality with its RING or DataDirect Networks with its combination of its Intelligent Memory Engine bust buffer and WOS object storage, just to name a few of the emerging options.

Taking on enterprise storage was not precisely the initial plan at Formation Data Systems, Mark Lewis, one of the company’s co-founders and its CEO, tells The Next Platform.

“We have been in beta for about nine months, and I will be honest, I thought we would have FormationOne generally available about three months ago,” Lewis explains. “It’s funny. We started more with a big data and Hadoop focus with our product, as well as with some of the object store use cases where everybody kind of was, and we found that there was very little uptake there right now. Big data is a little more storage hype than storage reality. So we have spent a lot more time on iSCSI, NFS, and the core legacy things, and that is where we have been getting our customer interest and traction. Companies that have bought a lot of NetApp arrays and they don’t want to buy any more. Ultimately, we think people will modernize and write more applications that use object stores, but for now there was a much better short-term play to run well with VMware, run well with NFS, and run with the legacy apps because that is where their economic challenges are.”

Lewis is no newbie to storage, and the fact that the company had to pivot so quickly shows just how volatile the enterprise storage space is right now.

Back in the 1980s, Lewis was a storage engineer at Digital Equipment, and when Compaq bought Digital in 1998, he was the general manager of the storage business for that upstart server maker. In the wake of Hewlett Packard’s acquisition of Compaq in 2002, Lewis moved over to EMC, where he was chief technology officer for five years before running other divisions; he also was a key executive behind a whopping 31 acquisitions by EMC, including buying VMware back in December 2003. Formation Data’s other co-founder, Andy Jenks, is a software engineer who made the leap to the venture capital markets, including stints at EMC Ventures, Khosla Ventures, and Stage One Capital. Speaking of venture capital, Formation Data raised $3.2 million in seed funding in April 2013 and another $15 million in Series A funding in July 2014, which has been used to do the development of the FormationOne storage platform over the past several years.

The Object Of Enterprise Storage’s Desire

The concept behind FormationOne was always to bring object, block, and file access to data on a scalable platform that is inspired by the scale-out storage in use by hyperscalers such as Google, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, and Facebook. It is just that the file and block layers became more important ahead of the product launch than expected, based on the targeting of the enterprise storage base. And Formation Data is a realist about the enterprise storage it is chasing. Lewis says that he breaks the storage market into three different groups.

The first is the high-end SAN arrays using Fibre Channel switching that back-end ERP systems and their databases, which Lewis says “will stay where it is” and that Formation Data is not going after that market. “That is like the mainframe of storage, and people are not going to touch that stuff,” he adds, and that is one reason why Cisco Systems this week announced a slew of Fibre Channel add-ons for its Nexus switches and rolled out a new monster MDS 9718 Fibre Channel switch that the big storage array makers will resell. (We would add that the revenue streams from these SAN arrays is diminishing, much as the flow of money for mainframes has in recent decades. Eventually, a long time from now perhaps, it will be a trickle and then nothing.)

Another part of the storage market is the “cheap and deep” object storage that is based on low-performance disk drives and exemplified by Cleversafe (now owned by IBM) and that also is being SwiftStack, WOS, and other products and homegrown object storage based on OpenStack Swift or Ceph as well as the object storage on the Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud Platform public clouds. The idea here is to have lots of scale at the absolute lowest cost.

Formation Data, at least initially, is focusing on the business-critical storage inside of enterprise datacenters that is based on block and file access with the assumption that enterprises will also want to have object storage, too, for their unstructured data and for future applications that will be based on object rather than block or file access. While none of the NetApp, EMC, IBM, Dell, or Hewlett Packard Enterprise machines that the FormationOne storage is aimed at as it launches is individually impressive, add it all up and it is a lot of storage at most companies, and the FormationOne stack is designed to scale high enough to consolidate this data onto a single cluster and do so on inexpensive iron from Supermicro to drive the overall cost of storage down.

Just to get the scale issue out of the way, Lewis confirms to The Next Platform that the architecture of the FormationOne object storage is design to span as many as 1,000 storage server nodes in a single instance, and up to ten domains, as the company calls each cluster, can be federated under a single management tool.

Significantly, this 1,000-node upper scale limit is the same as on EMC’s ScaleIO scale-out storage, which we detailed back in September and which only offers block storage at this time. Equally significantly, as far as high-speed Hadoop storage goes, EMC has done a good job of selling its Isilon storage to both Hadoop and HPC shops, so it makes sense for Formation Data to not try to crowd itself into this nascent market. That 1,000-node scalability is arguably at least one or two orders of magnitude larger than most customers will need – we are talking about multiple exabytes of data here for a fully configured setup. And that is why FormationOne is starting out scaling across 32 nodes at first. This is the same upper limit that VMware currently has with its Virtual SAN (VSAN) hyperconverged storage, although the EVO:RACK clusters aimed at large enterprises can federate ten clusters together as a single management domain for a total of 320 nodes. It looks like the initial FormationOne will do the same.

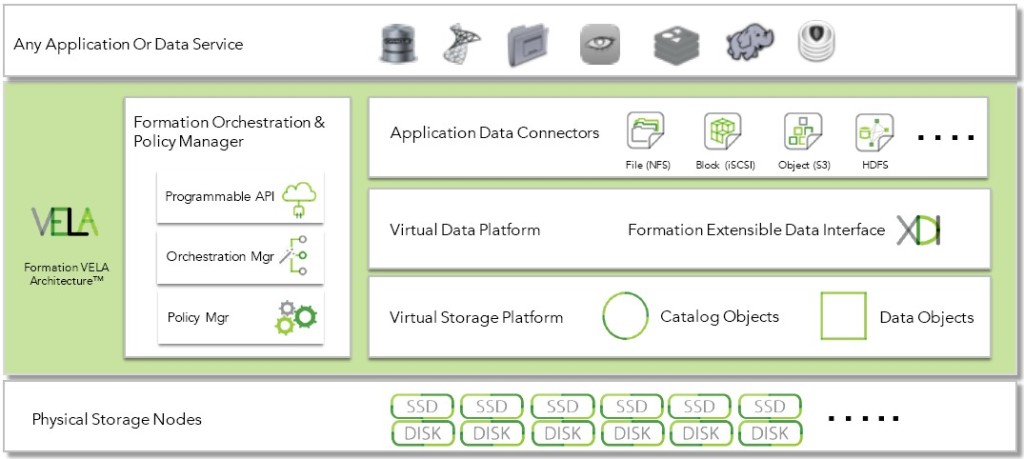

The FormationOne object storage is based on a bunch of open source software components and was designed to be deployed on Xeon servers with flash or disk storage. (Supermicro machines are the ones that Formation Data uses for testing and pricing comparisons.) The software has autotiering across the flash and disk to keep the hottest data on the flash, which has orders of magnitude more I/O operations per second and accordingly lower latencies for reads and writes (less so there).

The FormationOne stack starts with the Ubuntu Server variant of Linux, and uses the XFS file system to store data on each node in the object storage cluster. (Lewis says that the company looked at using ZFS and other file systems for this, but ultimately went with XFS.) The FormationOne stack makes use of the Thrift protocol, developed by Facebook, and RabbitMQ for the messaging parts of the storage, and the Redis in-memory key/value data store and the LevelDB key/value store for holding bits of its own management data. Lewis says that Formation Data looked at using Ceph as a starting point for developing the object storage layer, but decided to do it from scratch.

Unlike the homegrown object storage developed by Facebook as well as commercial variants, FormationOne does not use erasure coding techniques to shard the data across multiple disks and nodes and encode it for recovery in the event that a disk drive fails. Because Formation Data is not trying to hit the lowest cost possible, but is trying to deliver performance for both data recovery and data protection, the FormationOne object storage replicates data across multiple nodes either two or three times, depending on what the user wants, much as the Hadoop Distributed File System does. Over time, Lewis expects for the FormationOne stack to support multiple types of replication, and erasure coding could be added, too.

The software supports the iSCSI block, the NFS file, and the AWS S3 object storage protocols for data access, and it can also look like a HDFS to Hadoop data analytics clusters. A layer of software called the Extensible Data Interface, or XDI, is what provides the block, file, and HDFS overlays for the underlying and native object storage. These protocols can be mixed and matched on the same cluster, and all data is thin provisioned and in-line de-duplicated by default by the FormationOne software. The basic assumption of this stack is the same as with all hyperscale software: that the underlying hardware and the systems software on a node will fail, and that this should all be transparent to the object storage and not affect the applications that depend upon it.

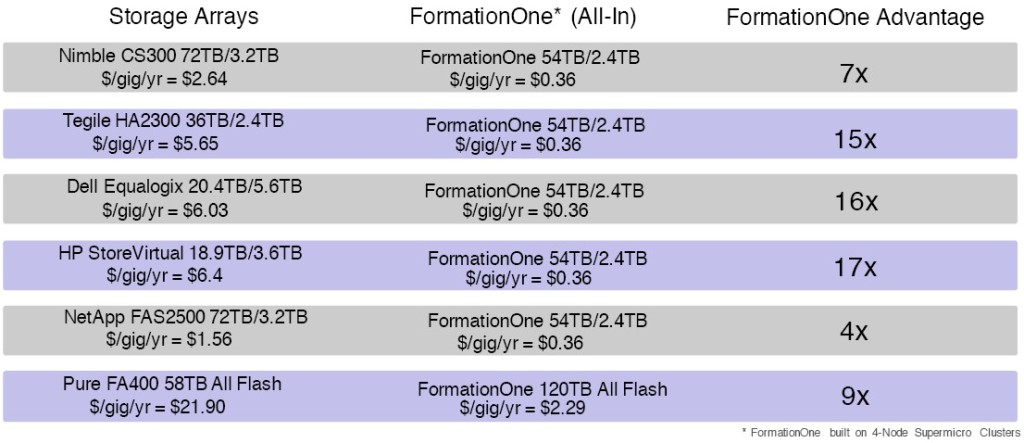

As a rule of thumb, Lewis says that the goal is for the FormationOne object storage (which again has block and file access methods) to offer a factor of 10X better total cost of ownership over the disk arrays sold by the incumbents in the datacenter. Here is how Lewis stacks up the various competition:

The comparisons are based on running FormationOne on a four-node cluster using Supermicro machines. The first four nodes are free for customers to use in a test environment, and the pricing for an annual subscription to FormationOne scales according to the capacity under management, not the number of nodes. A license to manage 100 TB of data comes to $10,000 per year for just the software, which works out to under a penny per month per GB. That is in the same competitive range as cloud storage from AWS, Google, and Microsoft, not including their data movement charges, which can really add up. (The cloud storage includes the hardware cost, too, obviously, while the FormationOne software licenses do not.) FormationOne can run on public clouds as long as they support Ubuntu Server, and companies could deploy the storage on their own gear as well as on the public cloud to get hybrid storage with the same access methods.

The one thing that FormationData is working on with its initial dozen early adopters is figuring out how FormationOne compares in terms of performance and price/performance with actual disk arrays when it runs on premises and in the public cloud, which will complement is TCO analysis.

Over time, FormationOne could also be tweaked to run in hyperconverged mode, pulling in distributed compute onto virtual machines on the same clusters that are running the distributed storage, much as VMware does with its VSAN and Nutanix does with Xtreme Computing Platform. But Lewis says that while hyperconvergence has taken off for niche applications like virtual desktop infrastructure or branch office applications, he believes that it has not taken off yet for the enterprise datacenter at large because companies do not like the appliance model because they want to be able to scale up their compute, storage, and networking independently of each other – a sentiment we shared last August when talking to Hewlett Packard Enterprise when discussing this very topic.

Be the first to comment